Many years ago, when I was working as a hospital security officer, I was sent to a patient unit regarding a “combative patient.” Oddly enough, healthcare workers rarely regard themselves as being in “combat” when a patient is grabbing, hitting, or kicking them; but, when they describe someone who is acting out at the moment, they often choose the adjective “combative” to describe the behavior they are observing.

As a result, over time I learned to expect any type of behavior when I heard the term “combative” come out over the radio. Because in the eyes of the staff it could mean anything from a visitor refusing to leave after visiting hours to a patient in the act of strangling a nurse, which was highly problematic.

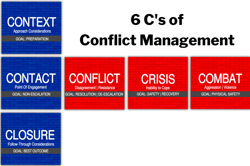

At Vistelar, we train according to the 6Cs of Conflict Management: Context, Contact, Conflict, Crisis, Combat, and Closure. The goal of the 6Cs is to stay on the blue brick road, meaning the path that leads from context, to contact, to closure, without straying onto the red brick road of conflict, crisis, or combat.

Combat, and Closure. The goal of the 6Cs is to stay on the blue brick road, meaning the path that leads from context, to contact, to closure, without straying onto the red brick road of conflict, crisis, or combat.

The 6Cs helps contact professionals, such as healthcare staff, stay on the safe path by identifying the context and levels of conflict they are experiencing, know how to respond as trained, and take appropriate action as necessary to keep themselves and others safe. The 6Cs helps contact professionals respond to all emergencies in a prepared manner, instead of naturally reacting to them when unprepared to do so.

Respond, Don’t React

Respond, Don’t React is a foundational principle we train at Vistelar. When I arrived on the floor that day, greeted by frightened stares from the unit staff, pointing towards the patient’s room and shouting that I needed to get in there, my natural urge was to rush into the room and take immediate action. But that in fact would have resulted in an unprepared and potentially dangerous reaction. Instead, I took a few moments and prepared to respond.

From the hallway, I could hear a male voice yelling from inside the room. While I approached, I stood back from the open doorway and looked inside, applying the Vistelar method of Proxemics 10-5-2. At the position of 10 Feet away, where we can safely Evaluate or Exit the scene, depending on the context of the situation. At this position of 10 feet from outside the room, I could continue to evaluate the context, using what I could first hear and then see, smell, or feel.

Once I understood the context to the best of my ability, I could decide whether to enter the room myself or call for more trained assistance/back-up. Would it be safe for me and others in the room if I were to enter alone? Would I need more security officers or maybe even the police? Until I understood the situation, its risks, and its threats, I wouldn’t be able to answer those questions.

I quickly did a risk assessment to evaluate if there were any risks to my safety before entering the room. I couldn’t see into the bathroom, so I didn’t know for sure if anyone else was hiding in there or behind the bed. There was nothing thrown on the floor or property damage indicating a struggle, or liquid on the floor that I could slip on. Also, there were no visibly obvious weapons of opportunity nearby, other than things he could throw from the nightstand. That said, there are always weapons of opportunity present in hospitals, i.e., things you can use to throw, hit, or cut.

I also did a visual threat assessment of the patient. I could see that he was sitting up in bed and yelling and cursing. He was not injuring himself or damaging any property. Both of his hands were visible and empty, so he appeared to be unarmed. But it was possible that he could be concealing something in the bedding or on the other side of the bed.

Since there was no immediate danger, I had time to gather more information from the staff. I asked for his name, so I could address him directly and put him at ease. For safety reasons, I asked what he was being treated for. I asked if there was anyone else in the room and they answered no. I also asked if they had ever seen any weapons in the room or if the patient had ever made any verbal threats. Also, was he ever moody, angry, or depressed?

I also asked if he had any cognitive challenges, altered consciousness, or mental illness. I asked how long he had been in the hospital and did they know what had set him off today? And perhaps most importantly, had he ever touched, struck, harmed, or otherwise become violent with staff or anyone else, during his visit.

The answers I received were surprising.

Very quickly I was able to build a picture of the angry patient in room 503. They said he had been in the hospital for a week and he was often angry and confused. They said he suffered from early-onset dementia and was being treated for a respiratory illness. They said he seldom had visitors and was sometimes confused about where he was.

Finally, they said he had once grabbed a nurse by the wrist, but did not injure her. They said they called this time because he was agitated to a higher degree than usual and threatened staff verbally when they approached to take vitals. Now armed with more information, I asked for one additional backup officer and waited for her to arrive.

Treat People with Dignity by Showing Them Respect

Now that I had more information about our patient, I could really apply some depth to Vistelar’s five approaches to Treat People with Dignity by Showing Them Respect. First, by understanding that he had memory challenges, I could see the world through his eyes better. By listening with all my senses, I could investigate how much he understood his circumstances and why he was angry, frightened, or frustrated. Then when I made contact with him, I could ask and explain why I was approaching him and offer options, and let him choose. And finally, I could give him an opportunity to reconsider, if necessary.

approaches to Treat People with Dignity by Showing Them Respect. First, by understanding that he had memory challenges, I could see the world through his eyes better. By listening with all my senses, I could investigate how much he understood his circumstances and why he was angry, frightened, or frustrated. Then when I made contact with him, I could ask and explain why I was approaching him and offer options, and let him choose. And finally, I could give him an opportunity to reconsider, if necessary.

When my backup arrived, I briefed her on the situation and we made a plan to enter the room. She would wait just outside of the door to watch for safety, while I entered the room and approached to 5 feet, where I could Communicate or Evade an assault if necessary. From five feet, I could position myself towards the side and foot of the bed, where he could see me but not reach me.

From there, I would also be between him and the door, so I could get out quickly, in the event he suddenly pulled a weapon out from under his bedding. I could also walk momentarily to the other side of the bed to see if anyone was hiding or if he was concealing a weapon. I could also get a good view of the bathroom and closet. While I did that, my backup officer could step just inside the door to watch for my safety and observe the patient.

It’s Showtime!

With our plan in hand, I prepared myself to enter the room by adopting a Showtime Mindset. I told myself “it’s showtime” to get ready for the interaction. Then I took a few deep breaths, stood up straight, put on my professional face, told myself I was the right person to handle the situation (positive self-talk), and prepared to step on to the stage, which in this case was a hospital room containing a sick, angry, confused, and probably frightened man.

As I walked toward the room I finally noticed a placard next to the door frame that read, “Contact Precautions.” That’s something no one had mentioned before. The placard gave instructions for entering and leaving the room, to minimize any possible transmission of disease or infection from patient to staff. The placard read as follows:

- BEFORE ENTERING ROOM

- WASH with soap and water at room entrance

- PUT ON FULL PPE gown, gloves, mask, and eye shield

- BEFORE LEAVING ROOM

- REMOVE FULL PPE gown, gloves, mask, and eyeshield

- DISPOSE OF ALL PPE in provided receptacle at room entrance

- WASH with soap and water at room entrance

NOTE: No dietary personnel may enter this room under any circumstances.

All other staff must report to nursing station first and follow all Droplet Isolation precautions.

Infection Control Department Ext. 555″

After reading that, I pointed it out to my partner. I then entered the room to begin washing. While washing, both of us watched the patient to see how he would react. He was still yelling and cursing, but he hadn’t noticed us yet. So when I was fully dressed in PPE, my partner washed and dressed as well. Finally, we were ready to make contact with the patient.

Again applying Proxemics 10-5-2, I approached the patient’s bed while moving into his field of vision off the foot of the bed. Once he saw me I did a Universal Greeting, taking into account that he may be experiencing memory challenges. I was also able to peer around the bed and the room to look for any other possible risks and threats.

Using the full benefit of the PPE, which was concealing my uniform, I decided to state that I worked in the hospital instead of immediately identifying myself as a security officer, in an effort to avoid escalating him. This is referred to as reducing your profile, a form of modeling intended to reduce a person’s anxiety and fear. Persons with memory challenges sometimes react negatively to the presence of police-style uniforms, because they often struggle with understanding their circumstances.

“Good afternoon, Tom. My name is Joel and I work here in the hospital. I can hear that you are very upset about something. You are safe with me here, so don’t worry. Can I ask you why you are angry?” Tom looked up at me and smiled. It was a reaction I didn’t expect but have seen many times since that day when interacting with angry dementia patients.

“Hey there! Are you going to take me home?” he asked. I answer Tom in a friendly tone, actually mirroring his new friendly tone. Very quickly, Tom and I were on friendly terms.

“Not just yet, Tom. I was just stopping in to visit and see why you were so mad.”

“Mad? Who’s mad? Something wrong?” Tom asked.

“Nah, just stopping in to see how things are going, Tom. Did you eat yet?” I asked.

Tom replied, “Great idea. Let’s get a beer and fire up the grill. I think I got some bratwurst in the freezer!”

Soon, my partner and I were sitting in chairs next to Tom’s bed and chatting about barbecues and baseball. Even when Tom finally realized where he was and who we were, he seemed appreciative of our time and the conversation. Tom even shared with us that his wife had recently died and his kids had moved far away. He felt isolated and alone. And on top of it all, he understood that he was struggling with his memory.

After our interaction with Tom, we were able to get a psychiatric and social work referral to get him more services. The psychiatric department worked with the medical staff to give them more intervention strategies for the nursing staff as well, part of which was using a Universal Greeting to help him ground himself when he struggles with his memory.

We, in security, offered the nursing staff some safety tips, like Proxemics 10-5-2, which included hand placement, distance, and positioning for when they had to get close to treat Tom at 2 feet or less. We also encouraged them to call us before Tom got too agitated and not to rush in when he was angry by starting Proxemics 10-5-2 just outside the entrance to his room.

Tom was soon discharged but on the day after the incident, while I was walking through the unit on a foot patrol, I heard Tom yelling from his room.

I simply stopped by, knocked on the door frame, and said without stepping into the room, “Good morning Tom, It’s Joel. What’s all the yelling about?” Tom looked toward me and his angry expression turned quickly to a huge smile.

“Hey, It’s my buddy, Joel. Where’s your friend? Who’s yelling? Hey, what’s with the monkey suit?,” referring to my uniform, because on the day we met I had been wearing full PPE. After I reminded him I was a hospital security officer, we had a good laugh.

That placard on the door that first day had stopped me in my tracks before I rushed into that room to see what was wrong with Tom. And even though the nurses knew my partner and I needed to take infection precautions, the heat of the moment had blotted it out of their minds.

Summary

Because of our training, in Showtime and Proxemics, we were protected from being infected that day or from compromising Tom’s recovery. We were also able to approach Tom and de-escalate him, simply with our presence and dialog.

Just as I was ready to say goodbye to Tom, a nutrition services worker (who was also not wearing PPE) rushed into the room with a tray full of food. I stopped her and quickly asked her to step back outside. She was surprised when I pointed out the isolation placard and when I informed her that she should always just deliver her food tray to the nurses’ station when she sees an isolation placard. She said that no one had ever trained her regarding the policy for isolation patients.

So who needs this training, you ask? If you work in a hospital, regardless of your role, you need this training. It will keep you, your fellow staff members, and patients under your care safer.