Enjoy this excerpt from one of our published books.

Chapter 7

Is Everything okay, Doctor?:

When Word-based Tactics fail

“In any moment of decision, the best thing you can do is the right thing.

The worst thing you can do is nothing.”

-Teddy Roosevelt

The doctor arrived on the unit and suddenly found himself surrounded by angry nurses, demanding action. “You seriously need to talk to your patient’s family!” the charge nurse said anxiously.

“Why, what’s up?” said the surprised doctor. He was a good doctor and well liked by the nursing staff. He was used to nurses speaking their mind, as he was approachable, showed them respect, and genuinely valued their opinions.

“They’ve been arguing and fighting all day. Now they are refusing to leave and it’s an hour after visiting hours! I was just about to call security!”

“No don’t do that,” pleaded the doctor. “If we call security, it might just make things worse. Let me see what I can do.”

“Please, be my guest. They are sure not listening to us,” complained the charge nurse, as the doctor headed towards his patient’s room.

As he approached down the hallway, he could already hear several voices involved in a heated argument and the television turned up at a loud volume. While walking down the hall, he glanced into the other rooms with their doors open and saw other patients sleeping or quietly watching television. When he passed the patient room next door, he saw a woman standing in the doorway with an anxious expression on her face. Before he could say anything she asked, “Is everything okay, doctor?”

“I’m sure it is. I’m going to talk to them now,” he answered in a reassuring tone.

The door to the problem patient’s room was also open. He could see the patient lying in her bed, watching television and appearing undistracted by the chaos surrounding her. On either side of her bed were two men involved in a heated verbal exchange, while pointing and shaking their fists at each other. At their sides were two women, often chiming in by cursing and threatening the other in turn. Crowded together in a recliner were two little girls, who were also staring at the television intently, as if tuning out a familiar background noise. The doctor entered the room unnoticed. Without making a sound he quietly walked around to another chair in the opposite corner of the room and sat waiting for the family to settle down. The argument seemed to go on forever, but after a few minutes one of the men turned to leave and walked towards the door. He noticed the doctor sitting there. “Who the f*** are you, motherf*****?!” he demanded.

To that, the doctor stood up and said, “I’m this patient’s physician and this has to stop!” Without answering, the man shoved the doctor back in his seat. When he attempted to stand again, the man’s wife was on him immediately, slapping and scratching his face. When the other couple tried to intervene, an all out brawl was sparked. By the time security arrived, the doctor was already bruised, battered, and bleeding from his mouth. The patient and the two other little girls were crying and screaming in the back of the room.

Taking Appropriate Action

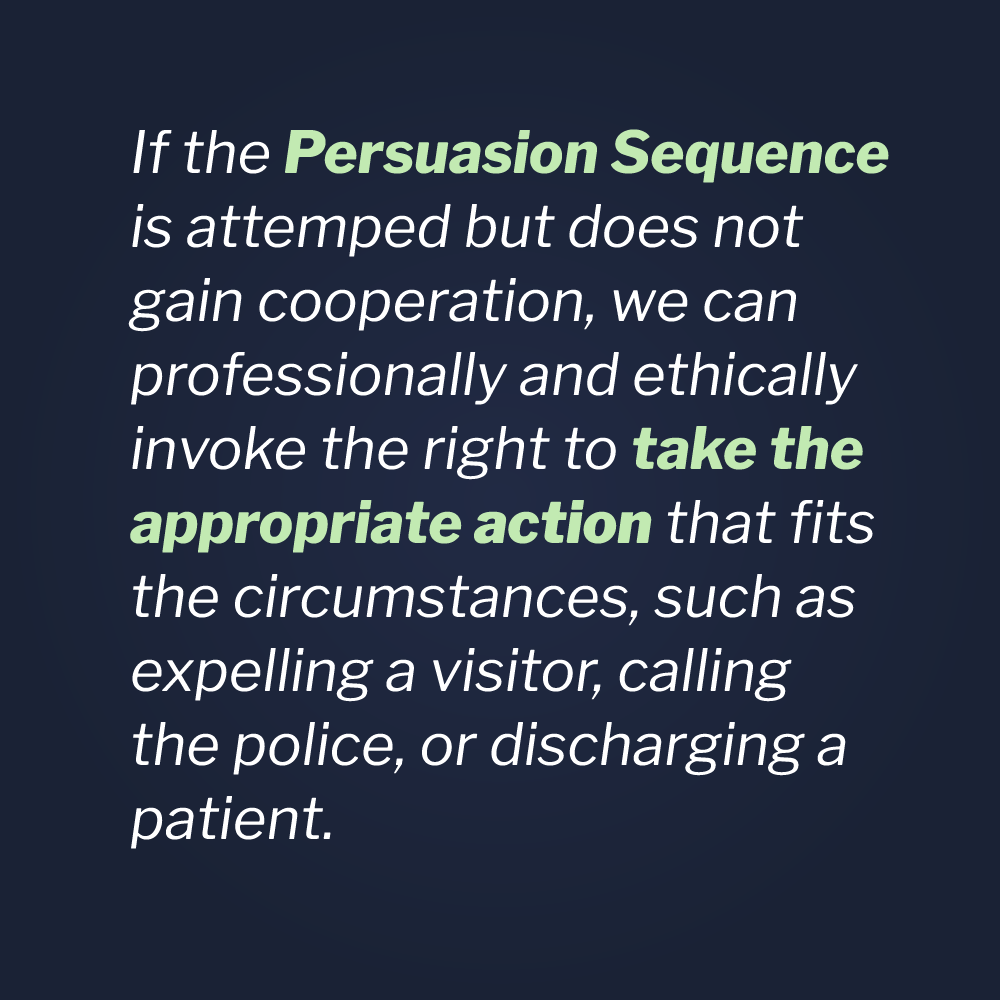

Word-based tactics may fail, therefore effective conflict management demands that other viable options exist. Once you have exhausted all verbal options and reconciliation is no longer a feasible or safe option, Taking Appropriate Action is the next step in managing conflict. Every action you take is safety and circumstantially dependent. The need to take action may occur at any time during a conflict situation and not only after all possible verbal options have failed.

The need to Take Appropriate Action, including physical action when justified, can occur at any point during the Persuasion Sequence or at any other time, during contact with a challenging individual. The need for action occurs when the Persuasion Sequence is attempted but does not gain cooperation. If that happens, we can professionally and ethically invoke the right to take the appropriate action that fits the circumstances, such as expelling a visitor, calling the police, or discharging a patient.

the Persuasion Sequence or at any other time, during contact with a challenging individual. The need for action occurs when the Persuasion Sequence is attempted but does not gain cooperation. If that happens, we can professionally and ethically invoke the right to take the appropriate action that fits the circumstances, such as expelling a visitor, calling the police, or discharging a patient.

The action you take should always depend on your personal safety and the safety of your patients, peers, staff, and visitors to your facility, in accord with the policies and procedures of your facility. Your particular institution may have regulations and policies that set your rules of engagement, which you should follow to the best of your ability. Those rules of engagement will always apply, as long as they don’t conflict with your constitutional right of self-defense. Also, according to Joint Commission, Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services and OSHA standards, healthcare professionals have a responsibility to protect people under their care. In this day and age of rampant healthcare violence there are no more innocent bystanders!

Of course, the action you take must be reasonable in light of the circumstances and must be in line with your state’s statutes concerning self-defense and the defense of others. When forced to defend others or ourselves, the force we use need not be a perfect selection, only a reasonable one. That is an important distinction, in that we are often forced to make a quick decision in uncertain and rapidly evolving circumstances. Although, ultimately, others will likely judge your use of force, the justification for its use is viewable only from your perspective, based on what you believed to be true at the time you act. Second-guessing and Monday morning quarterbacking are irrelevant except for the purposes of debriefing with an eye on improvement. Documenting, in writing, that you attempted the Persuasion Sequence will not only show that you performed to the best of your ability, it will protect you should legal and professional concerns arise.

That understood, you might not always have time to complete or even begin a Universal Greeting or Persuasion Sequence. Sudden assaults are rare, but do occur. The actions you take must be a trained technique that complies with your institutions rules of engagement or an untrained technique justifiable under the law according to the totality of the circumstances.

Healthcare professionals frequently deal with patients who suffer from trauma, brain injuries, psychiatric crises or who may be under the influence of drugs, alcohol, or general anesthesia. The failure to train healthcare staff in physical stabilization techniques is not only dangerous but also misguided. The option to never go “hands-on” does not exist in the real world, especially in the medical profession. Therefore, the responsibility for hospitals and clinics to train security and other hospital staff in physical stabilization techniques is a foregone conclusion. Through Vistelar’s conflict management training program, clinicians, security, and support staff learn to forecast, non-escalate, disengage, de-escalate, and stabilize patients as necessary for the safety of both patients and providers.

An immediate safety concern is always a reason to Take Appropriate Action and a safety concern may develop at any time. You might be involved in a routine contact with a patient, employing the five approaches to showing respect, having a Showtime Mindset, going Beyond Active Listening, Redirecting verbal abuse and using the Persuasion Sequence but, despite your best efforts, safety concerns can arise.

Tactical Proxemics

Your ability to act depends on your understanding of tactical Proxemics 10-5-2 techniques, i.e., proper distance, positioning and hand placement. It also depends on your ability to sense and recognize danger. The recognition of an immediate danger is based upon your ability to assess threat and the level of trust you place in your own instincts. Unfortunately, as we discussed, human beings are quick to dismiss their own instincts. Healthcare workers may be particularly impaired for two reasons: Violence Myth #7 (“Things aren’t really that bad”) and the false sense of security healthcare workers commonly develop. The following story is a good example.

A nurse had just finished her shift in the emergency room and decided to stop at an all night grocery on the way home. It was late and she didn’t like to shop alone after dark but she didn’t like waking up to an empty refrigerator either, so she dismissed her fears and stopped for some basic supplies.

She had a new car and didn’t like to park it in crowded areas and risk door dings, so she parked it a little further away from the entrance. While walking across the parking lot she noticed someone driving slowly through the empty part of the large shopping center parking lot next door. She wondered to herself what they were looking for, as it seemed a little odd.

Once inside, she grabbed a cart and headed through the aisles. As always was the case, she started filling her cart with more than she’d originally intended to buy. While looking at some cosmetics, she noticed a man staring at her. As is true with most women, this wasn’t a new experience for her. Many times in the past she had encountered the “creepy guy gaze.” Being accustomed to being ogled on occasion, she just dismissed it and went on. But as the minutes passed, she noticed that the creepy guy kept turning up in every aisle she turned down. He would look her up and down, while obviously pretending to look at items on the shelves. He didn’t have a cart and wasn’t carrying anything either. He would just pick up an item or two, place them back on the shelves and nonchalantly follow her through the store at a distance.

Finally, when she turned down the next aisle he disappeared. Feeling somewhat relieved, she decided to forgo anymore shopping and head to the register. She looked around the store on her way up to the front, but couldn’t catch sight of the creepy guy. Though she had been in that very same situation a few times before, she said it was my voice in her ear that gave her pause on that particular evening.

Two weeks prior to that evening, she attended one of my training sessions on the prevention and management of healthcare violence. In that training, I told the class to reclaim their natural sense of fear they had lost through their training and experience as providers. She said she particularly recalled my definition of a false sense of security, which comes from taking a risk several times and not getting hurt, then drawing a false conclusion that what you’re doing is safe. It may not be the first ten times or even the first hundred times you do something dangerous that you get hurt or killed. It may happen on the one hundred and first time. Finally, she said she could hear me telling her to trust the little hairs on the back of her neck. On this night, the little hairs on the back of her neck were sticking straight up.

She said she knew what she had to do. That is, ask for help. Though she felt silly and embarrassed, she decided to tell the cashier about the creepy guy. In most cases we wouldn’t judge someone else as being silly or weak for asking for help in these circumstances, but we still might judge ourselves harshly. In order to keep safe, sometimes we have to give ourselves a break for being cautious. If the worst did happen, both the victim and the Monday morning quarterback would be thinking that she coulda, shoulda, woulda asked for help.

“Excuse me,” she said to the cashier. “I’m probably just being silly, but some creepy guy was staring at me in the store. Can someone walk me to my car or just watch to make sure I’m safe?”

“Oh dear!” said the cashier. “Don’t feel silly, you were right to ask. Let me get the manager.”

The assistant manager happened to be a man so they sent him. He was only too glad to walk the young nurse to her car, although it’s not necessary for our support persons to always be men, because women can support us as well. As a matter of fact, I’ll take a woman with some basic violence awareness and safety training over an untrained man any day. That said, he put on his jacket and valiantly escorted her out into the lot.

As they approached her car, she noticed that someone had parked next to her, all the way out there in the empty part of the lot. As the manager was kind of chatty, he didn’t notice the look of fear on her face when she recognized it as the same suspicious looking car that was patrolling the lot when she first arrived at the store. While the manager kept talking about how he was only glad to escort her and wished more women would ask, curiosity overtook her judgment and she simply continued up to the parked cars.

When finally close enough, she looked through the windshield of the strange vehicle. Crouched down in the seat was the creepy guy, with his seat reclined far back enough to conceal his presence, but still give him a view of the lot. “That’s him!” she shouted while pointing at the windshield. The startled manager started to approach the driver’s side when creepy guy sat up, turned over the engine and sped away.

In the words of Bob Willis, “Threat assessment is the study of what human beings do before they assault you. In poker, experienced players can predict the future by noticing certain “tells” in the behavior or other players. Victims of assaults sometimes say that they knew they were about to be attacked but unfortunately chose not to act.”

One of the things I’ve heard most often when debriefing victims of violent assaults is, “It came out of the blue!” Over my long career I’ve learned that’s almost never the case. Usually, attackers tell their victims many times that an attack is coming, long before it actually happens. Sudden assaults are rare but do occur. That said, even in a sudden assault, the signs that violence is possible are usually present, in the form of pre-attack postures and other behavior patterns. Professionals, whether they are police officers or healthcare providers, need to always be on the job when in uniform. In the case of healthcare workers, they are on the job whenever they are wearing scrubs. It’s not about being paranoid. It’s about being relaxed but alert and then taking appropriate action when threats are identified, and when situations occur that require increased attention and caution.

STAMP and the Gateway Behaviors of Violence are two examples of behavior patterns that can reliably predict violent outcomes. Experienced professional fighters know what is about to happen, before it does. Another pattern of behavior that is related to STAMP is pre-attack postures.

Some pre-attack postures are dramatic, like the clenching of a fist. Others are subtle, like someone invading your personal space. There are early warning signs of rising emotion that can be heard, seen, or even felt. Increased tone and volume is easily recognized and should be respected, but murmuring under the breath or conspicuously ignoring attempts to communicate are also reliable signs of building tension. Angry expressions and threatening eye contact are also easily recognized. But the avoidance of eye contact or a blank expression, sometimes referred to as the thousand- yard stare, can be equally dangerous and too subtle to recognize by unaware providers who don’t have their heads in the game. There are also body postures, such as shifting weight from one foot to another, shoulder shifting or “blading” the body at an angle. Increased tension can also be felt in the form of the dead weight tactic, when trying to lift or move a patient.

There is also your intuitive sense, built on your natural instincts and experience. If something seems out of the ordinary or threatening, it probably is. In those cases, take the most conservative approach, get help, and Take Appropriate Action. Don’t wait for the attack to come. Instead, anticipate it and take measures to prevent it. Learning to disengage and using self-protection skills are essential for anyone working in healthcare.

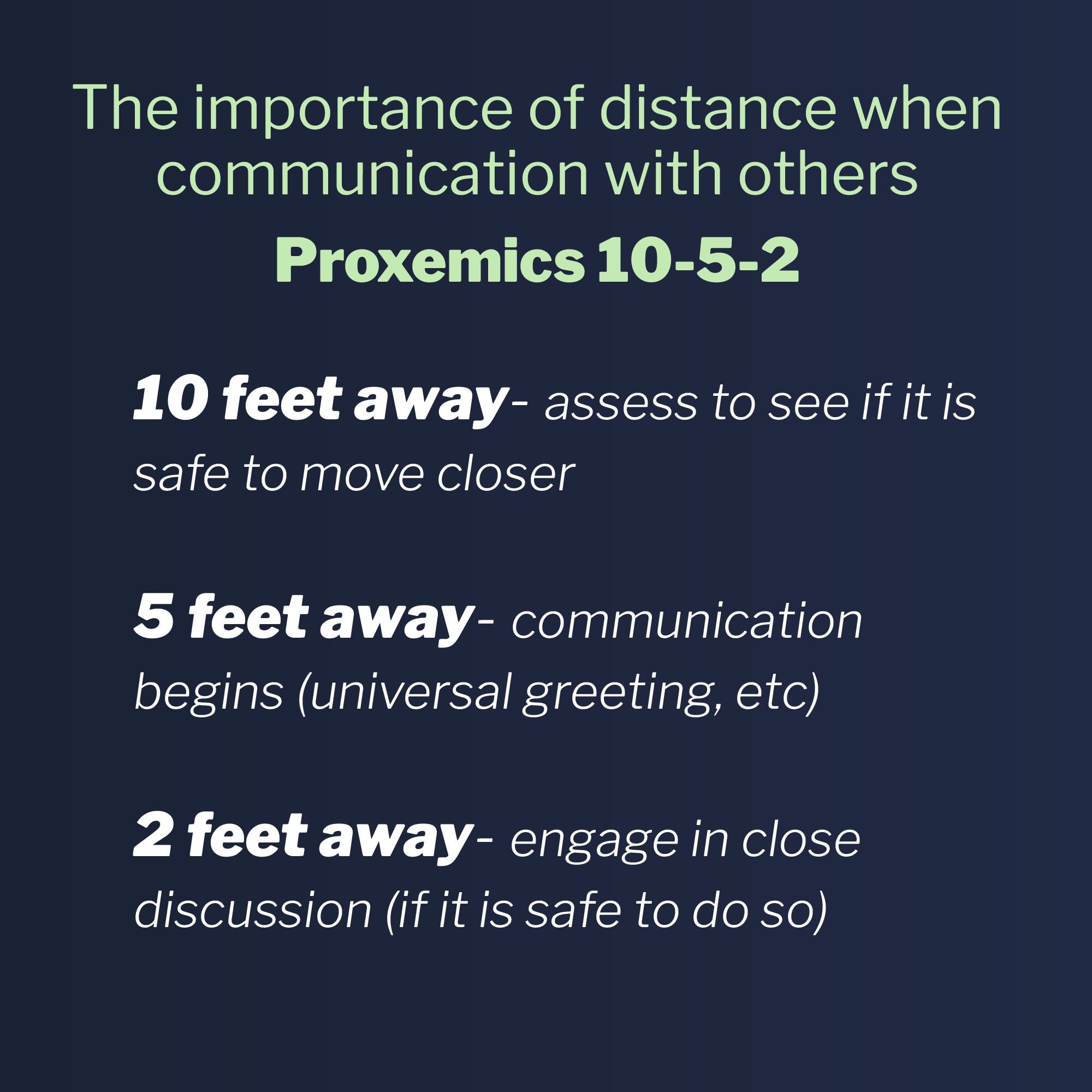

The tipping point is often related to distance. As a preventive measure and assessment tool, we can employ the Proxemics 10-5-2 tactic. Remember, if you are at ten feet, you can leave or not enter in the first place. Healthcare providers generally tend to go too fast, get too close, and say too much before they’ve made an initial assessment of the scene. Ironic, considering healthcare workers are constantly assessing patients.

In an environment crowded with people and crammed with equipment, such as many hospital settings, ten feet can seem like a huge distance. An ER exam room may be barely ten feet in depth! Still, our assessment often begins with the patient’s chart and the circumstances of the patient’s complaint. Armed with what we already know about a patient, we can continue our assessment by what we hear when approaching the room. So, that ten feet of evaluation space really begins in the hallway before we ever get to the room.

When we get to the door, we need to think of that space as the patient’s current living space and not as an extension of our workspace. Whether the door is open or not, we need to knock on the door or doorframe, wait a few seconds, knock again, then open slowly if unanswered. Standing just outside the doorframe, we need to begin our evaluation. How many people are in the room? Is the patient present? How is everyone behaving? Are there any potential hidden danger areas, corners, curtains, and closed restroom doors?

In many hospital exam rooms, when we’re standing in the doorway, we are already in the “five feet zone”. That is the point at which we will need to communicate or evade if a threat is identified or an attack occurs. At five feet you could be fully involved in communicating with a patient or visitor, but ready to take necessary action to disengage from an attack. Through Vistelar’s conflict management training program, providers learn effective stance and movement skills, such as sweep and escape, designed to maximize their ability to evade an attacker even when given one second or less to react. These skills are vital when you

can’t just turn your back and leave because of how vulnerable you’ve become and how quickly you can be assaulted at that range.

While communicating at five feet, providers can begin to form relationships that are incompatible with uncooperative and even violent behavior. Having a Showtime Mindset and using the Universal Greeting can set the tone for what happens next. It is also a point at which you can continue your threat assessment and determine if it’s safe to approach your patient and operate. By operate, we mean examine and treat your patient. Once you’ve made the determination that the patient is ready to be approached and you’ve stated your intentions by use of the Universal Greeting, you can approach to within two feet. At that point, if we’re threatened or attacked, we’ll be required to defend ourselves and escape. But by assessing at ten feet and communicating at five feet, we’ve greatly reduced the possibility that an attack will occur. When we rush in too quickly, things are far more likely to go badly.

uncooperative and even violent behavior. Having a Showtime Mindset and using the Universal Greeting can set the tone for what happens next. It is also a point at which you can continue your threat assessment and determine if it’s safe to approach your patient and operate. By operate, we mean examine and treat your patient. Once you’ve made the determination that the patient is ready to be approached and you’ve stated your intentions by use of the Universal Greeting, you can approach to within two feet. At that point, if we’re threatened or attacked, we’ll be required to defend ourselves and escape. But by assessing at ten feet and communicating at five feet, we’ve greatly reduced the possibility that an attack will occur. When we rush in too quickly, things are far more likely to go badly.

But what about those times when we’re forced to Take Appropriate Action (when word-based tactics fail), either by calling the police, dismissing a patient, or even defending ourselves physically? Does taking action then constitute a failure on the part of providers?

On one occasion I was asked by a child protective service agency to assist with a family who was in foster care. The parents had court-ordered supervised visits with their biological children who were in the physical custody of a foster family. During the parent visits, the father would get confrontational with the foster parents and curse, yell, and otherwise behave inappropriately in front of the children. Even after repeated attempts to supervise visits by the foster parents and case managers, the father’s behavior got progressively worse. Finally, he began to threaten the foster parents and caseworkers. Fearing for the safety of the children and agency staff members, the agency reached out for assistance.

I formulated a safety plan that first included a risk assessment that included a background check of the parents, a review of any records, a debriefing of the caseworkers, the orders from the court, and all the particulars of the case. A risk assessment is a gathering of information intended to predict possible threats from individuals or situations, based on what we know. Then I asked to meet with the parents prior to scheduling their next visit, in order to make a threat assessment by assessing their behavior. A threat assessment is an evaluation of behaviors and situations at the point of impact, based on what we can observe in the moment.

I scheduled the meeting in a secure setting at the agency, instead of the parents’ home. When they arrived for our meeting, I greeted them with a Universal Greeting. “Good Afternoon, I’m Joel Lashley. I’m the security officer for the agency. It’s a pleasure to meet you both. Can I ask your names?”

“Hello, we’re Mr. and Mrs. Jackson,” said the father. The mother didn’t speak. In fact, she rarely spoke at all and only in response to questions.

“The reason we’re here is so I could meet you both and discuss how I can assist you in having successful visits with your kids. May I see your paper work and identification?” They produced the items I requested and I escorted them to an office where we could talk privately.

As I expected, once we were alone the father became confrontational. He raised his voice and started cursing. He also denied threatening anyone or otherwise behaving badly during prior visits. He also demanded new caseworkers and that future visits be scheduled at his home. His wife kept her head down and seemed to just tune us both out. Using the Persuasion Sequence, I laid down some ground rules.

“Mr. Jackson, can I ask you to please lower your voice and stop cursing? We have to prepare for your visit with your children and this is the sort of behavior that we are concerned about.”

“I can talk anyway I want! I’m a grown man!” he shouted.

“I’m not telling you how to speak anywhere else. But this is a place of business and it has to be an appropriate environment for children and families. So we don’t allow any cursing, yelling, or threatening. The way you talk somewhere else is your own business, but not here. This is a private office,” I explained in a concerned tone of voice and at a low volume.

“F*** that!” he replied while rolling his eyes, but also mimicking my calmer tone and volume, as he was already following me down to a calmer state of mind. But he was still cursing so I continued to set context.

“Mr. Jackson, I am here to make sure you can visit with your kids. I have determined that your behavior is threatening and uncooperative. If you refuse to cooperate with me, I’ll have to cancel your visits until they can be re-evaluated by the court.”

“You can’t do that!” he said sternly, but still not yelling.

“We have two choices, Mr. Jackson, one good one and one bad one. The good one is, you can cooperate with me and agree to my terms. Then your visits with your kids will proceed on schedule. I will also write in my report for the court that you were cooperative. But if you refuse to hear me out and agree to my terms, I will report this conversation and recommend that future visits be terminated because you are too much of a risk to our staff and your children. Do you understand, Mr. Jackson?”

“Okay. I didn’t curse or threaten anyone anyway,” he replied.

“Well, that’s good. Then you have nothing to worry about. I will be on hand for your next few meetings. If you’re safe and cooperative with everything, I will testify to that on your behalf. I want to be on your side. Can you help with that? It’s all up to you what happens next.”

Mr. Jackson agreed to my terms, which were to meet with the caseworkers, immediately following our meeting. He also agreed to continue working with the assigned caseworkers. He also agreed not to yell, curse, or threaten during future visits and cooperate with staff direction and coaching.

The meeting with this family’s caseworkers was scheduled immediately after my private meeting with the Jacksons. Much to my surprise, we would not be alone. When I led the Jacksons to the conference room for the next meeting, we found it to be crowded. Along with the caseworkers were their supervisor, the foster parents, the children’s psychologist, the parents’ attorney, and many other people I didn’t recognize. With at least a dozen people crowded around the conference table, the meeting began.

Seated next to his attorney and seemingly emboldened by his presence, Mr. Jackson looked poised for a fight. As soon as one of the caseworkers attempted to open the meeting, he interrupted her, saying, “I don’t want to hear anything out of you! I don’t want you on my case anymore!”

“Mr. Jackson,” I interjected. “We just talked about this. Do you want to proceed or should I just cancel this meeting now?”

“I’m sorry.” He replied and sat quietly. The look on everyone’s face was priceless as his immediate cooperation was totally unexpected.

At times during the meeting, Mr. Jackson would raise his voice or drop an f-bomb. At those junctures I would just say, “Mr. Jackson”, and he would apologize and settle down. On another occasion, he caught himself, apologized, and stopped before I could say anything.

After a few curious looks from his attorney, the meeting continued swimmingly. Then after two hours of hard negotiation and discussion, Mr. Jackson received news he wasn’t prepared for. The visits would continue at the agency until further notice and the children would remain in foster care. After hearing that, he blew up. “You f***ing b***h!” he shouted while lunging across the table at the caseworker. Before he could reach her I was on him. The security officer and I took him out into the common area where he continued to fight. Ultimately we handcuffed him and called the police to take custody.

While we waited for the police to arrive, Mr. and Mrs. Jackson wept softly. Finally, I addressed the father while we waited. “Mr. Jackson, it’s really none of my business now. I know this must be hard. But you have to understand. If you keep behaving like this, they will never give you your kids back.”

To that, he looked me in the eye and asked, “Really?”

For the first time, the mother looked up and spoke without being spoken to. She looked directly at her husband and said, “Do you get it now?”

After the police came and took Mr. Jackson away, I directed Mrs. Jackson to the bus stop and went home. All of the other people from our meeting had already left. I was certain that complaints would soon pile in from the agency and the parent’s attorney about what a disaster the meeting had been. Sure enough, by the next morning my voicemail and email were both flooded with messages. However, these responses weren’t at all what I expected. They were filled with praise about the meeting and requests to continue having me supervise future meetings. The caseworkers in particular, said they had never accomplished as much with this client at a single meeting, as they always had to be cancelled within a few minutes. The agency also wanted my help with other difficult cases.

In every encounter, things may not go as expected. Outcomes can even appear different to different people. But as Mr. Klugiewicz often says, “We must have a pre-planned, practiced response so that no matter where things end up, we always look good.”