Enjoy this excerpt from one of our published books.

Chapter 9

If you didn't write it down, it never happened:

Review and Report

“Trust is a beautiful thing, but it has no place in police work.”

-Gary T, Klugiewicz

After any incident, no matter how large or small, it is important to review and report so mistakes aren’t repeated and good practices are identified. Reviewing an incident will improve future performance and build consistency. Report writing protects you and your employer from speculation and documents your professionalism. Whenever we’re looking back to a past incident in an effort to justify our performance, if we failed to file a report in the first place, as far as everyone else is concerned, it never happened that way. Report writing is a chore and it may also be human nature to try to forget about unpleasant experiences, but it is an essential task that enables us to advance and learn. A serious incident requires that a reconstructive effort is made and an analysis performed.

There will never be two incidents or two perspectives that are exactly the same. Even if you aren’t the only person there, you are still the only one who has the information required to relate the incident as you saw it and experienced it. Others may critique your work, second-guess you and maybe even blame you, so it is important to articulate your perspective skillfully and detail exactly what you knew at the moment you took action.

Reporting on Incidents from Your Point of View

Articulation is a skill that, ironically, many human service professionals lack. Complicating the situation, eyewitness testimony, video evidence and pictures are very likely tainted, because they were generated from a “passive” location, resulting in different perspectives and points-of-view than yours. In some cases, the very video recordings you thought would save you turn out to be worthless. Or worse yet, end up representing you in an ambiguous or even negative light. Any evidence that is subject to interpretation— such as video evidence—is viewed through the lens of a subjective observer. Photographic images and video evidence are also questionable for technical reasons, as these media are subject to distortion and confined to two dimensions.

Eyewitness testimony is often unreliable, because human memory can be affected by stress, emotion, and the passage of time. Many recent high profile incidents have demonstrated that lots of people can witness an incident and all report different versions of the event. Despite any evidence and others testimony, you will generally have only one chance to tell your story. Therefore, it must be truthful according to your best recollection and it must be well done.

Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin has recently renewed focus on that very important aspect. Developing a culture incompatible with violence requires that intelligence information is generated and that providers are held accountable to take action. Once a violent incident or a condition that can result in violence is identified, whatever is learned enhances the ability to prevent future violence. Accountability will demand that we learn from the past and implement policies and procedures that have proven themselves in the field. Providers will ultimately learn awareness regarding the patterns leading to violence and utilize avoidance strategies and intervention tactics that they can apply early in the cycle of violence often preventing even the possibility of conflict.

culture incompatible with violence requires that intelligence information is generated and that providers are held accountable to take action. Once a violent incident or a condition that can result in violence is identified, whatever is learned enhances the ability to prevent future violence. Accountability will demand that we learn from the past and implement policies and procedures that have proven themselves in the field. Providers will ultimately learn awareness regarding the patterns leading to violence and utilize avoidance strategies and intervention tactics that they can apply early in the cycle of violence often preventing even the possibility of conflict.

The first question that may be asked is, “Whose responsibility is it to document a risk or violent incident?” Is it the provider, their supervisor, an administrator, the security department, risk management, or a law enforcement agency? The fact is that many of those people may be involved, but it is first and foremost your responsibility. You may be required to generate a written report, respond to a supervisor’s questions, submit to an interview or even testify at a hearing.

Creating a Culture that is Incompatible with Violence

The idea of writing a report or testifying in court terrifies many people, especially ones who are not called upon frequently to do so. Some may even fear that they are being accused of being involved in some way or otherwise suspect. Employers in the healthcare profession must first make it clear to providers and support staff that they have permission to report and take proper action when violent conditions occur. Then, and only then, can they make clear the expectation that everyone take action, no matter what their role is in the organization. Then healthcare facilities need to train providers how to identify unsafe conditions. Finally, they need to train staff how to take proper action, up to and including report writing. Only then can they truly begin to hold people accountable for their actions or inactions.

There are many levels of conflict in any incident. The first conflict might be either a violent incident that you just experienced or a condition of risk that you just identified, but it doesn’t necessarily end there. A second conflict may involve justifying your actions to your peers, your employer, and in rare cases the police or in court.

Finally, we are often conflicted ourselves about whether we did the right thing. All these conflicts are related but require different abilities on your part. Having your “ducks in a row” is critical and fortunately well within your ability, especially because you have hopefully embraced the contents of this book. Vistelar’s conflict management methodologies are a “system” that gets us through the incident and all the subsequent related conflicts.

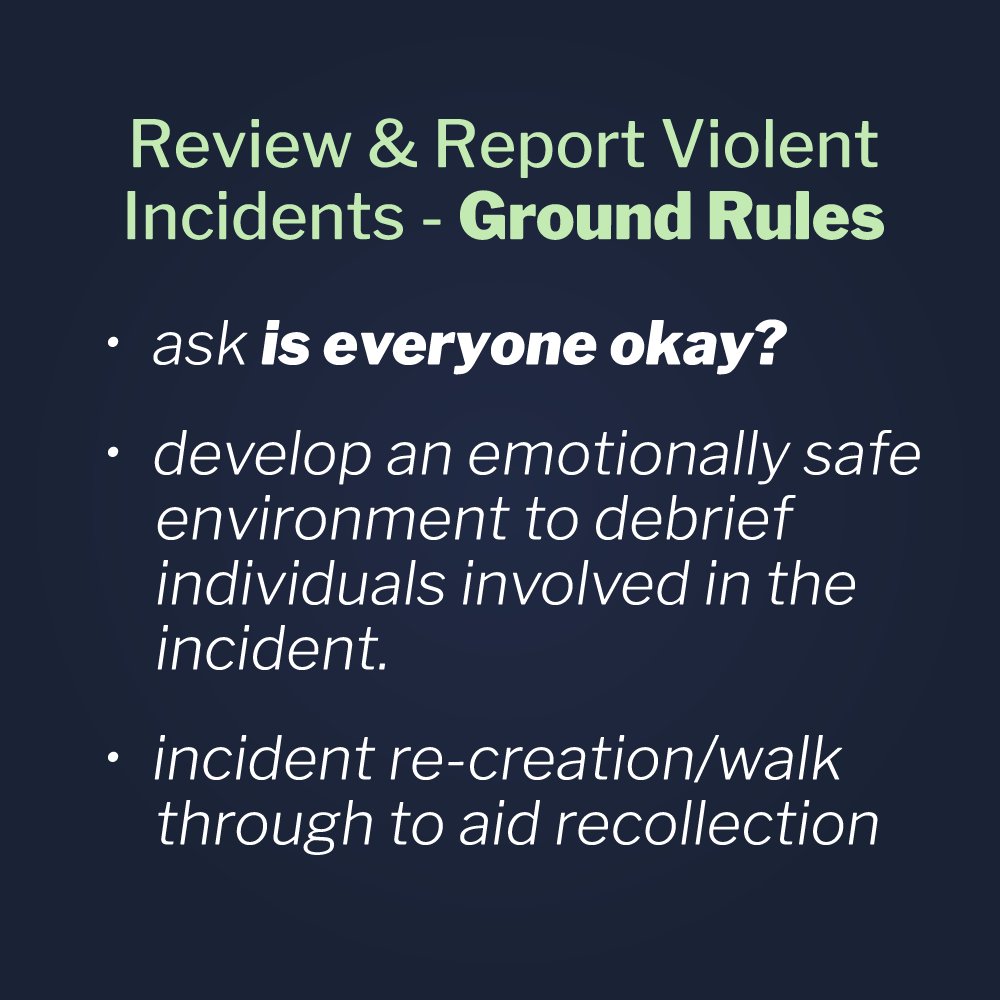

Now that we have established that it is everybody’s responsibility to review and report violent incidents and unsafe conditions, there are some ground rules. The first one of these rules is the “is everybody ok?” rule. Debriefing an incident is important but the welfare of those involved is the first priority. Forcing articulation or conducting an interview prematurely will not only harvest poor information, it will alienate everyone to the system and reduce future performance. Before debriefing can begin, the incident has to be stabilized and everyone involved must be both physically and emotionally safe.

The United States is currently dealing with renewed fallout of individuals struggling with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, from the ranks of military and law enforcement personnel who have not been effectively reintroduced back into a “normal” social environment. Suicides are endemic in both the military and law enforcement communities because the physical and psychological welfare and normalization of these heroic people was too long an afterthought. A whole generation of Vietnam veterans returned to the demands of re-socialization without a general concern for their individual welfare; resulting in more of them dying by suicide, and drug and alcohol abuse, than by enemy fire. No matter the level and type of conflict, the initial step of the debriefing process must be to ask the question, “Is everyone okay?”

The next stage is to develop an emotionally safe environment. Debriefing is not intended to be an interrogation or fault finding mission, but a fact finding mission intended to report the truth to the best of our ability and to improve future performance. The purpose is to make us better the next time. Subsequent remedial measures are a legally recognized concept. If something could have been done better, it’s important for everyone involved to take note and improve. Admitting our mistakes, while looking towards improvement, does not constitute an admission of liability. It’s the way we learn as an institution and demonstrate our commitment to safety.

Debriefing also isolates what we did well and causes us to repeat good tactics and techniques. It is not about where we failed, because previously our experience was lacking, but where we can now, based on this incident, improve our performance. It is about what we have learned. The fact is that no one starts their day trying to figure out where they can screw up! The difference between a mistake and liability is reputation. The first time our performance is lacking, is usually because of our lack of experience; but the second and subsequent time our performance is lacking, is likely because we didn’t debrief and bother to learn and seek improvement.

After the initial debrief, which is usually a discussion, the next stage may be an actual re-creation or walk through. After a traumatic event we may not remember things well. Human memory is complex and consists of recall and recollection. Recall is what we initially remember. Recollection, or associative memory, sometimes requires sensory stimuli to prompt memory. Going back to the scene, seeing objects or the environment, smelling the smells and touching or feeling things may fill gaps in memory. The walk-through is an attempt to identify the totality of the circumstances and the truth. Sometimes, during and after a traumatic event, focus becomes limited. By expanding our focus the totality of the circumstance becomes clearer.

Recognition memory completes the mosaic of an event by adding the feeling and emotion to your experience and training. It reflects not only on the objective but the subjective aspect—not just the cognitive but the emotional and psychological aspects as well. Emotional intelligence is a known and recognized entity. It is an important part of our decision making process and must be a part of recounting an event. How were you feeling at the time you took action? How may your state of mind have affected your actions? Were you in fear for your safety or the safety of others when you took action? Did you perceive that there was no other recourse? Did you attempt other means to stabilize the situation? These aren’t questions that seek blame. Instead, they are questions that clarify our intentions and often justify our course of action.

When necessary a debriefing can be accomplished by interviewing the individual players in an incident. In the busy task-driven environment of healthcare, group debriefings can be very difficult to pull off. Still, when individual players can share their perspectives together, better recall and safety planning becomes possible. That said, some people might be inappropriate to include in-group debriefings. This might include, of course, suspects, victims, patients, and visitors who may have been witnesses.

Every Perspective Is Unique

It is important to understand what you perceived but also what others perceived. These individual and collective parts help assemble a clearer picture of an incident. None of us are looming above an incident and watching it in its totality; we all observe varying parts of the entire event. The truth can only be assembled though a collaboration between the different observers, because no one person saw the whole thing. It may also be helpful to have trainers, risk managers, corporation attorneys, supervisors and other experts present. Not with the intention of spinning the story, but to make sure all bases are covered and that no element is overlooked.

collective parts help assemble a clearer picture of an incident. None of us are looming above an incident and watching it in its totality; we all observe varying parts of the entire event. The truth can only be assembled though a collaboration between the different observers, because no one person saw the whole thing. It may also be helpful to have trainers, risk managers, corporation attorneys, supervisors and other experts present. Not with the intention of spinning the story, but to make sure all bases are covered and that no element is overlooked.

Total recall and a search for the truth is an evolving process. Even if some people are less than truthful, the members of a debriefing group will ferret out and identify discrepancies. When preparing to debrief an incident, get yourself ready by going through the strategies, tactics and techniques taught in this book. An incident is less like a photograph and more like a movie. When filing your report, your articulation must describe how this event evolved and all the influences that exerted pressure upon it. Ultimately you are the one who makes the reader walk in your shoes.

When necessary, creating some emotional distance from an incident can allow you to achieve some professional detachment. Harry Dolan, retired Chief of Police of Raleigh, North Carolina, uses what he calls the 24-hour rule. Overnight, anger or fear may subside. After a short time to decompress, improved recall and collaboration may result.

Although it’s often important to capture information from witnesses and victims while it’s fresh and people are available, when debriefing other responders you can take a brief pause, step back, and cool off, so better information can rise to the surface. Questions like, Why were you there? What did you see? What threat assessment did you do? Did you use a Universal Greeting? Did you use the Persuasion Sequence? Did you use Redirections? What dangers were present? Did you employ a pre-planned and practiced response? Did you follow through properly after the event? Did you learn anything from this incident? Perhaps three of the most important questions you will be asked are: Is everybody okay? Did you respond as trained? If not, did you respond in a manner that was justified under the circumstances? All these questions become clearer when we have cool heads.

When analyzing an incident with an eye on improving future performance, we should always consider the closure principle: Did we leave the people we were dealing with in better condition than when we found them at their worst? How were they ultimately safer because of your presence and your actions? Look at the “big picture” and consider how others were affected by your intervention. Did they benefit from your intervention? Were they negatively impacted in anyway? Is there anything left to do post-incident? Although the incident itself may have been negative, opportunities for positive outcomes should never be squandered because we failed to review and report.