“Improve Your Institution's Responses to Mental Health Crises ” - Episode 21

Host: Brine Hamilton, CHPA

Guests: Joel Lashley and Gary Klugiewicz

Subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Google Play or YouTube.

Today, the largest institution in America for the treatment of mentally ill people is the Los Angeles County Jail, followed by jails in New York and Chicago. How is it that we wound up housing our mentally ill and cognitively disabled people in jails? Is it just a fact of life that mentally ill and cognitively challenged people commit more crimes than healthy and neurotypical people, so they end up in jail? …Or is the answer more complex?

In addition, emergency rooms absorb around 12 million mental health emergency visits a year. These visits can be not only enormously costly but largely ineffective, due to lack of training by clinical staff to manage their patient’s mental health needs.

On this episode Brine talks to Gary and Joel about how and what kind of trained techniques can have a positive impact on an institution’s collective response to a critical incident.

Some key takeaways from the discussion will include:

- The role of a special management team comprised of various professionals in responding to crisis situations within an institution and how consistent interdepartmental training is crucial to achieve a positive outcome

- How treating individuals with dignity by showing them respect keeps everyone safer

- Why employing “Non-Escalation” can be as important as “De-Escalation”

- Using empathy – what is the other person’s reality vs. your own – is essential when communicating with someone in severe crisis

Brine Hamilton: Welcome to the Confidence in Conflict Podcast. My name is Brine Hamilton. I’m an advisory board member for Vistelar, and I’ll be your host for this episode. I’m joined today by Joel and Gary, and I’ll give them an opportunity to fill you in on their backgrounds and why we’re having this discussion today about mental health awareness.

Joel Lashley: Hello, Brine. Nice to see you again. My name’s Joel Lashley. I work for a Vistelar, a conflict management company. I worked for 30 years in healthcare security, which I know is near and dear to your heart. My particular interest is in mental health and cognitive challenges.

Gary Klugiewicz: My name is Gary Klugiewicz, I also work for Vistelar. My background is in law enforcement. I spent 25 years at the Milwaukee County Sheriff’s Department, but why the significant for a mental health week is as spent seven years as the lead officer for the special management team. We’ll talk about that more later.

Gary Klugiewicz: But very simply, we had 300 inmates on psychotropic meds in our jail, and I was in charge of them, working with our staff who work with them. Then beyond that, I’ve trained all over the country and the world, teaching people how to respond to people with mental illness, and especially focusing now on healthcare and education.

Brine Hamilton: Awesome stuff. Now, as I mentioned, we’re going to be focusing on mental health awareness, and we’ll be referring back to Joel’s article as well, Treading Water, which is linked in the description in the show notes.

Rising rates of Mental Health Struggles

Brine Hamilton: Now, depending on the numbers that you look at, the conservative numbers say one in five, the less conservative numbers say one in three adults, do experience a mental health crisis at some point. So, although there’s a lot of stigmas around that, they’re starting to be recognized, but it’s not to say that they don’t exist. What are some of the concerns that we may not be aware of that impact individuals dealing with mental health issues or struggles?

Joel Lashley: Well, I think the way to look at it is from two sides. One is that, mental health and cognitive disabilities are on the increase we know, as are numbers of people with dementia, including age-related dementia, and Alzheimer’s. Our population is aging, we’re going to see a doubling the amount of numbers of people with cognitive challenges by the middle of this century.

Joel Lashley: Also, more children are being born in the autism spectrum, and with other challenges. But also we’re seeing mental health concerns increases in opioid addiction, fentanyl, things like that. These challenges aren’t going away. As a matter of fact, they’re becoming an increasing challenge. We’ve never really gotten the other side is, especially that we have for treatment.

Gary Klugiewicz: One of the things that I look at, I look at from the practitioner side, the person who has to interact with the person with mental illness, and cognitive challenges. The point of the matter is that whether that’s a police officer on the street, whether that’s social services dealing with the amount of homeless that we have through our country, many of them have mental health issues, dealing with the hospitals.

Gary Klugiewicz: Because there’s two ways that people really come in contact with the authorities. One is that they’re picked up on the street by the police and brought to the hospital, or they show up in the emergency room. The point of measure is that from there, it just is blossomed from there.

Gary Klugiewicz: Then add to the fact that dealing with education is that, think of all the people that are in education, the kids that have trauma issues, they have mental health issues, or they have all kinds of issues, poverty, everything. So, all that compiles to make it more and more difficult.

Gary Klugiewicz: Again, they are stigmatized, whether they’re acting a little bit strange, whether you say it, I don’t know if I can dare say it, they’re just crazy. I mean, because that’s how people talk about it on the street. Whether they have you say you have a mental health issue, all those people are coming in contact with authorities, coming in contact with people in businesses, and it’s making everything much more difficult.

Brine Hamilton: Absolutely. I guess historically, when we look at treatment facilities there again, there’s a lot of stigmas around the old facilities that used to exist. They had bad reputations, people didn’t necessarily want those facilities in their communities. Then we had the media influence, so we had movies like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. So, those facilities don’t exist anymore, and Joel, I know you talked about this. There was originally a plan to rectify this situation, but it just never happened. Do you want to unpack that a little bit?

The History of Mental Illness

Joel Lashley: Yeah. Classically, we’ve never really had the kind of facility that we needed, or never really got to that point where we could handle the amount of the challenges that we had with mental illness and cognitive challenges. Back when we look at the old days, we think about what were dungeons for under castles? They were for prisoners, and a lot of times they were people with mental illness because we didn’t know what to do with them.

Joel Lashley: Even as back when we think about the old Civil War, the middle of the last century, just before the war there was a big discovery that a lot of people with mental illness were being housed in prisons and jails, and they were ill-equipped to deal with them. There’s a lot of victimization and challenges there.

Joel Lashley: So, there was a big movement at that time led by a great American named Dorothea Dix, a very interesting person who was really the founder of mental health treatment and hospitals in America, but also influence around the world in her work. She was a leader as a woman, and as American, in making sure that people that we finally started to treat and provide services for people with mental illness.

Joel Lashley: But it was just getting rolling, and then certainly by the middle of the next century, some of the hospitals were huge. They were underfunded, they were overcrowded. I mean, we’re talking 50% over capacity by the time that I was born in the ’60s. It really wasn’t well-managed. So, we saw still large populations of people in jails, and then they started to close them down because of some of these discoveries.

Joel Lashley: Famous incidents like the famous Geraldo Rivera report where his career was born. He snuck into one of these big facilities and filmed it … Because it was a disaster. Because we’d kept this big secret. Nobody funded it, the government didn’t fund it, people didn’t want to know about it. They dropped their loved ones off at the door, and they thought they were going to be protected and well cared for, and that didn’t happen.

Joel Lashley: Then when people discover what they were really like, and as far back as the ’40s even in movies, like The Snake Pit, a famous movie from 1948 that featured a mental health facility that was kind of a hell hole. So, this started this cultural impetus.

Joel Lashley: Then people started to get the idea that we needed help here, so John Kennedy, JFK, because of the bipartisan initiatives inside the government said, we need to do something for the mentally ill. We don’t want to go back to these institutions, so let’s close all those down, and let’s have community clinics.

Joel Lashley: Well, by the time they got that rolling, and still the One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, the novel came out, and then the movie came out, and then famously Robert Kennedy went to that institution that Geraldo Rivera would sneak in afterwards, and saw it. He came out and said, “This place is a snake pit,” and it was the biggest, and most famous mental institution in America.

Joel Lashley: So, the tide had come, the sweeping social contract across America was that we need to do better for mental ill, institutions are a failure, so we’re going to make community clinics. But eventually, they were unfunded starting at the state level. The state said, “Okay, we’re going to get out of the mental health business.” There was no federal funding for them, so less than half of those community clinics that John F. Kennedy wanted to get built, got built. Then they were defunded.

Joel Lashley: So, now we have no institution, not enough trained psychiatrists, hospitals are starting to close their psychiatric inpatient units. Now, finding hospitals with locked psychiatric inpatient unit is an exception now, rather than the rule. So where did people go? Today, presently, I know Gary has a perspective on that because the reaction to what we do for people, where they ended up, and just to lead into that, Gary, is where they end up was, they would go into records in emergency rooms. This started immediately after they were defunded. People would present to emergency rooms, there was no place, no beds for them, nowhere to go. It would take anywhere from three days to a month to get a bed.

Joel Lashley: So where did they go? Back out into the street. They wound up homeless, wound up in jails. So we were back kind of to where we started at the beginning of the whole process 100 years earlier. Now the biggest institutions in America are famously jail. We’ve all heard the reference to LA County Jail as being the biggest mental health facility in the country. The Chicago jail system, also famously large, the second largest mental health facility.

Joel Lashley: We’ve seen, working with Gary all these years, there’s the good, bad and the ugly. But I think Gary, understanding that system we saw started in Milwaukee County that we can do this well, if we’re required to do it. What I mean by that is, if our mentally ill population is going to wind up in jail, and they’re going to wind up in our emergency rooms, then we can train and have systems in place until we finally get a grip on the situation. I know Gary will be able to talk about his experience, which I would consider to be the right way to do that, in a facility like a prison or a jail.

Gary Klugiewicz: One of the things is that, when they decided they’re going to let everyone out of the major state hospitals, and they promised that we’re going to do these community mental health clinics. That was the promise. Unfortunately like many promises from government, is that they didn’t fund them. If you don’t fund them, they don’t happen, or they don’t last because funding runs out.

Gary Klugiewicz: So, the truth of the matter is, today we really do have community mental health clinics. They’re called jails. That’s where they are now, they’re jails. Again, they start out probably at the hospital, but eventually either they get transferred to the jail, or they go off in the street and they get picked up and they end up in jail. So they’re in jail.

Gary Klugiewicz: So the whole point is, how are you going to handle these people that are coming in here, that have really mental health issues? They really don’t belong in a jail, but they’re here. So what do you do? Well, in Milwaukee county, in the early ’90s, we built a new jail. They actually wanted to do it right, and so they actually had a special management unit. For the first time instead of putting them in … When I started out in the late ’70s, our special management unit was a bull pen down in the basement, just like the old castles, where you had people that were just locked up forever, and they’re covered in their your own feces. I mean, that’s the reality of that time in our history. Still, today to some degree, it still exists.

Gary Klugiewicz: But we put together a special management team where we put together specially trained deputies, social workers and a psychiatrist, and we put them together in a team, and we actually were dealing with, at that time, 300 inmates on psychotropic meds. Some were in a special housing unit, and there was single, individual rooms in a special management area. But also we had two pods that just had special management inmates in there, and they were run by our people.

Gary Klugiewicz: It was a great time because these people were specially trained how to manage this. We’ll talk about training a little bit later, but just talking about, they’re specially trained, and they work together, and in fact they love being there.

Gary Klugiewicz: In fact, when we started doing this and even in the ’90s, they always said, “SMT?” That was on our thing, SMT. “What does that stand for?” Some of the deputies would say, “Some More Thorazine.” They would call it, and I’d say, “No, no no. It stands for, Simply More Talented.”

Gary Klugiewicz: I will tell you in my career, I’ve run correction emergency response teams, I’ve run trainings for all kinds of teams. The best team I ever worked on was the special management team because these people really, truly cared about the people they were handling. Some of them were criminals, most of them were, but there was no place else to put them. So that’s where we had them.

Gary Klugiewicz: Again, I just wanted to share this one with you, is that when you think that this can happen in a jail, every year, we had a Christmas party for them where we brought in some people to sing for them, some music, we’d have Christmas cookies, we’d have all good stuff. Now, this is the deputies doing this. Not those social workers. But the deputies along with the social workers who put this all together for them. So it can happen, but it’s still, a jail is not a place for a person experiencing mental health issues. There has to be a better way of doing it. But up until now, we haven’t found it.

To provide proper treatment, training is key

Joel Lashley: What I think is interesting about that experience, and has always fascinated me about Gary’s involvement and experience in the special management team and in that jail is, they proved that if that’s where we are, we can provide the kind of treatment that they need.

Joel Lashley: So, what did they need? They needed resources, treatment, beds, training. So, where are they going now? They’re going to emergency rooms and into jail. So what’s required in emergency rooms and jails? Training. While we’re waiting on those facilities because that’s the only place for them to go right now.

Joel Lashley: I think it’s ironic that in many cases, the first real meaningful treatment that a lot of those people got in their life was probably in that jail. Sadly, maybe the only treatment they ever got after they left that jail. It’s an indictment of the system, but also proof that we can train and prepare professionals, we can prepare environments to receive them and treat them better, not only with dignity and respect, but meaningful treatment, of which treating people with dignity and showing them respect is part of that meaningful treatment.

It’s an indictment of the system, but also proof that we can train and prepare professionals, we can prepare environments to receive them and treat them better, not only with dignity and respect, but meaningful treatment, of which treating people with dignity and showing them respect is part of that meaningful treatment.

Joel Lashley: Because, Gary, I would say that when you have a bunch of deputies putting together Christmas parties for that population, it may not fit with the social narrative right now. These people had that big heart, they had that experience working with people with those challenges, and what did we see? I mean, it’s very encouraging.

Joel Lashley: Right now, if they go to the emergency room on average, they’re going to wait from three to 30 days. If they can’t wait that three and 30 days, or there’s no stop gap, where do they go until we can house them? They’re going onto the street. The average American goes down the street, and they see a guy in the middle of winter in a T-shirt eating out of a garbage can, the average American thinks, “Well, the police will see them, pick them up, and take them to the magic place.”

Joel Lashley: So there’s no magic place. There is no magic place, and the police will sadly tell you in these big cities and urban populations, we drive by. Because there’s no place to take them. They’ll do what they can, there’s famously stories of police gathering up their own shoes and stuff, and passing them off to the homeless. So these are good, decent, well meaning, compassionate people, your average police officer on the street, and the corrections officers in prisons and jails. That’s an indictment of the system though, not of the people working in the hospitals, and the people working in the prisons in jail.

Joel Lashley: That’s very chilling what Gary just shared with us. I mean, you think about it, Dorothea Dix was dealing in the 1840s with people being held in prisons that were basically hellholes. Then we’re talking about in the ’70s, in a bullpen, in a basement, covered with your own feces. Now, is that an indictment of our system? But what he’s proven is that through the right kind of training, and this is what we need in hospitals, as a physician working in an emergency room, those teams.

Joel Lashley: Do they take people that are under stress? They don’t, and they wind up in crisis because we don’t know how to approach them, we don’t know how to manage them. Do they have the kind of training? The entire system is overwhelmed. In less than half the counties in America is a practicing psychiatrist. I mean, there are no resources. We’re doing the best we can. So it really is a crisis. It’s a mental health crisis, a national mental health crisis.

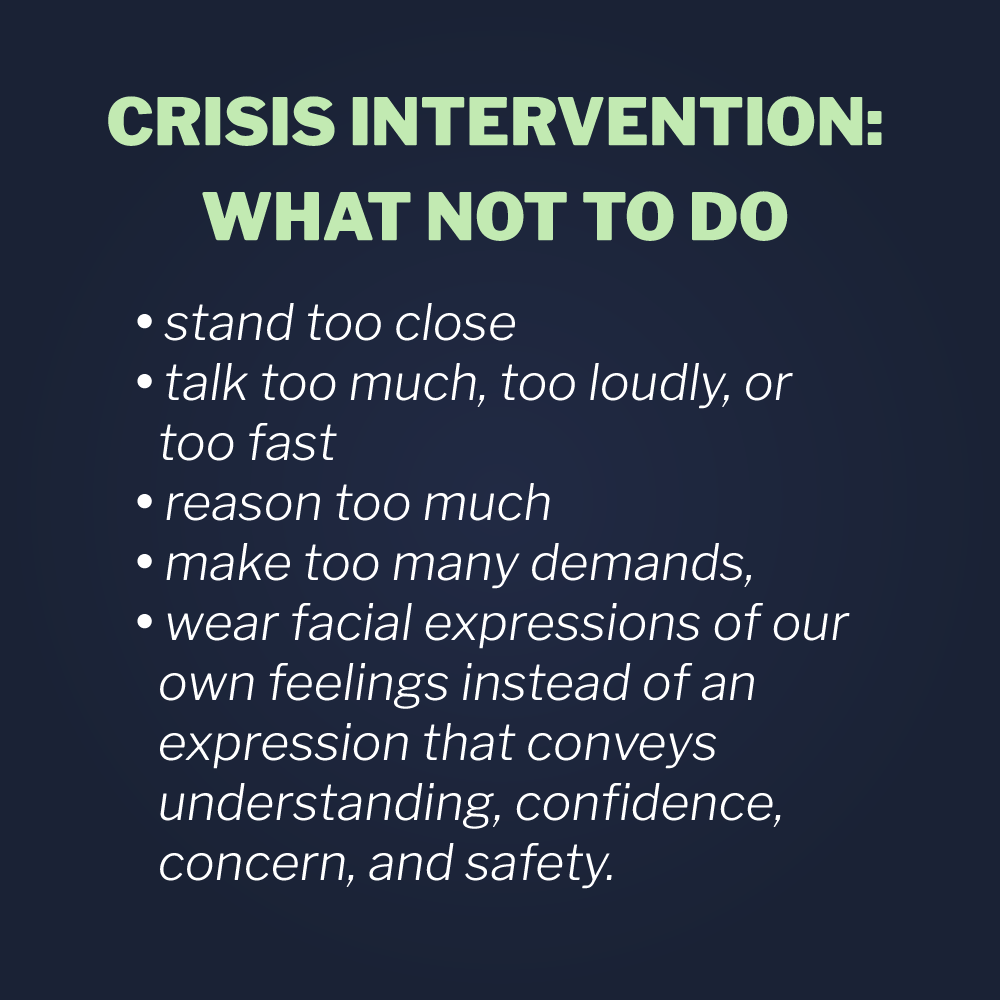

Gary Klugiewicz: I think one of the things that we need to focus on is what we can do to train our people, to be able to respond, rather than react to when someone comes in. Whether that be coming to my store, coming to my hospital, coming to my school, coming to my jail, how to interact best with them. One of the things that Joel has done a great job on, because we want to give some takeaways here of, what to do is that you have to think about what are the mistakes that the common professional makes as they approach someone? What do people do when you get close to people, rather than what they should do?

Joel Lashley: Well, typically we get too close, we talk too fast, say too much, talk too loud, and touch unnecessarily. That’s just a natural reaction because we’re trying to help people, so what do we do? We get in there and we help, and often, if not usually, the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

unnecessarily. That’s just a natural reaction because we’re trying to help people, so what do we do? We get in there and we help, and often, if not usually, the straw that breaks the camel’s back.

Gary Klugiewicz: So, really the first thing that really you need to do is, we need to be able to assess people. We always talk that you arrive at a scene, you assess what you have, evaluate before moving in to see what you have.

Gary Klugiewicz: Again, it doesn’t take a long time to figure out someone is having some difficulties. Whether it be intoxication, mental illness, whatever, I think that’s really important that we understand that. That we could see there’s something different about them, and because they’re different, and they’re not acting as a quote-unquote normal person would, that we have a way of approaching them. That is, not getting too close, not talking too loud, not saying too much, and just slow it down. We talk about how to make that first … We don’t want to have to de-escalate a person with mental health issues.

Using The Universal Greeting

Gary Klugiewicz: It’s very difficult to de-escalate anybody in crisis, but especially if you’re having some cognitive issues yourself, then it becomes very difficult. So we’d rather not start it on that path. So we like to start in very slowly. In terms of how to do that, do what we call a universal greeting, very calm, very collected, how to get some information, and say you’re here to help. Rather than, “What’s your problem, Jack?” It’s a whole different way of looking at it.

Gary Klugiewicz: If you come into a room and someone’s yelling and screaming, it’s not helpful to say, “What’s your problem, Jack?” You may ask, “Good evening, my name is nurse Gary, I’m working here on the floor. I couldn’t help but notice that something’s going on in the room. Are you okay? Is there something I can do to help?”

Gary Klugiewicz: Wouldn’t that be a better way of approaching it rather than putting gasoline on the fire? Then Joel says, there’s somethings you should do in every situation in terms of these cognitive management strategies. There’s certain things you should do whenever you’re dealing with anybody who is in crisis, no matter what the reason, anger, and mental health, intoxication, doesn’t matter. Why don’t you just talk about that for a second, Joel?

Effective Crisis Intervention Tactics

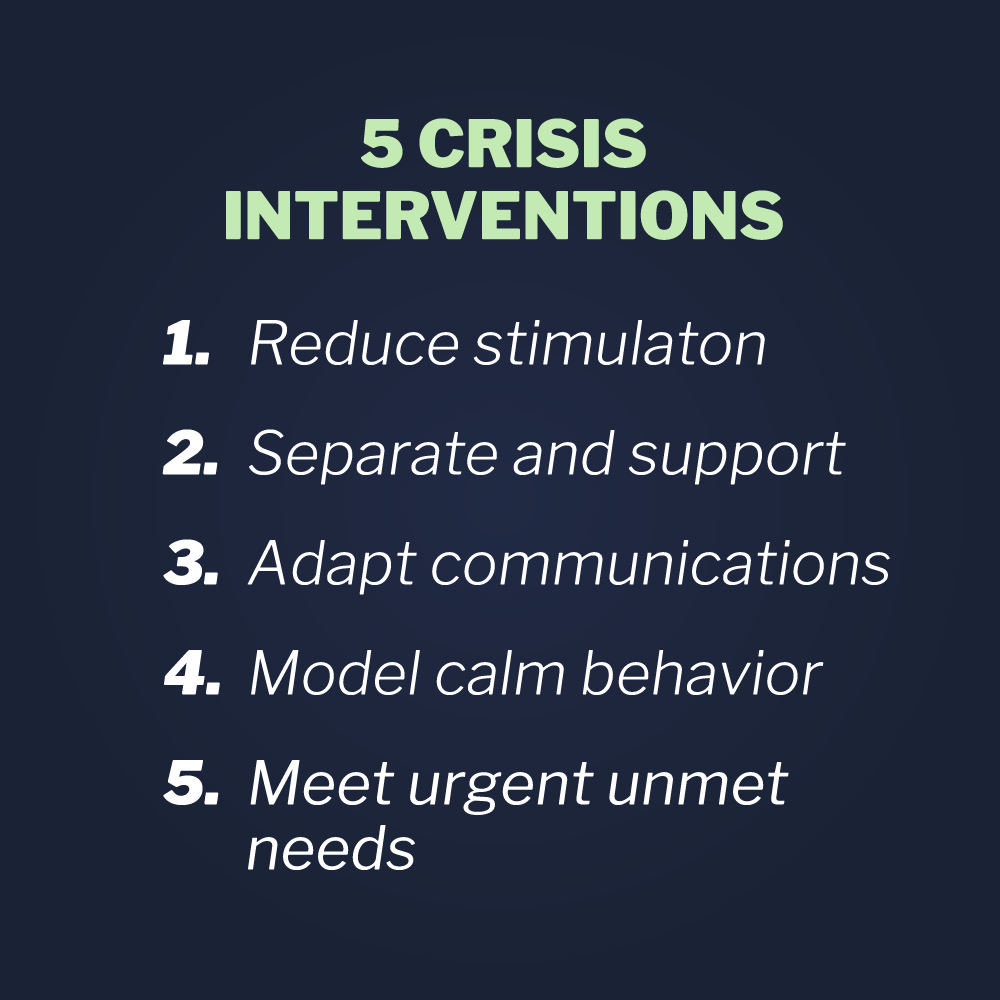

Joel Lashley: Sure. When we talk about individual and team approaches, the first thing we need to do, because it’s natural to match behavior, all behavior equalizes, when someone’s kind of acting manic, and they’re yelling, and they’re loud, believe it or not, our natural impulse is to match that behavior. Get real close and go, “Hi, you’re in the hospital. Sir, do you know where you are? Do you know who the president is? We push people from stress into crisis because we think that’s how you make an assessment of that initial contact.

Joel Lashley: All of a sudden we’ve given them all this stimulation. So, step one is modeling the behavior you want to see, good distance, position, hand placement. My communication alignment, what am I saying with my face, my tone, my voice? Reverse yelling, famously as Gary was in the jail way back in the days. We can’t tell people to calm down, but we can lead them down with our presence.

Joel Lashley: Then reducing stimulation. The rest of my teams, they’re running in to fix, and help, and push people over the edge. Instead, they’re going to say that I’m making contact. I’m having that communication, so they’re going to give me the right kind of support. That’s one voice, that we’re not all talking at once, “Hey buddy, calm down. Hey, you’re going to be all right. Hey you’re good to go,” which is just more stimulation. So, one voice to stimulation.

people over the edge. Instead, they’re going to say that I’m making contact. I’m having that communication, so they’re going to give me the right kind of support. That’s one voice, that we’re not all talking at once, “Hey buddy, calm down. Hey, you’re going to be all right. Hey you’re good to go,” which is just more stimulation. So, one voice to stimulation.

Joel Lashley: Getting them out of that crowded waiting room into a back hallway where it’s nice and quiet, turn the lights down a little bit, a place to sit. That’s separate and support. I can’t remove them from the scene, so I’ll remove the scene from them. I’ll get all the people back, turn down the lights a little bit, close the privacy curtain so I can safely observe them, but cut down on stimulation a little bit.

Joel Lashley: Adapting communication, like Gary touched on already, begins with that universal greeting. I’m this big, scary, strange guy in a uniform. No, I’m not. My name is Joel. I work here in the hospital. The reason I’m here is, my job is to keep people safe. I’m glad you’re here because we can help you. So, can I ask you to sit down and have a seat? Would you like some water?

Joel Lashley: That leads into urgent, unmet needs. People don’t act out for their diagnosis. They act out for reasons. They’re overstimulated, or they have an urgent unmet need, or they feel threatened in some way. So, we train people to manage that triad, feeling threatened, have an urgent need that’s not being met. I’m being overstimulated through those approaches, then we don’t start the negative dance, as Gary always says. We don’t light the fuse.

Joel Lashley: That’s non escalation. Non escalation is foundational to what we teach. It’s what we say and do to keep people from climbing up on that ledge. De-escalation is what you say and do to keep them from jumping. Like Gary said, that’s much harder, much harder. If we know what to say and do to keep them from climbing up there in the first place, we can save a lot of people. Until we can get the grips on the situation where, what do we do next?

Joel Lashley: Because what’s the average psychiatric stay recommended from the experts? Twenty days, 20 days. Think about that. What are we going to do with these people? We’re not going to get them into a bed for 30 days, so what are they going to do? They’re going to eat out of a garbage can in an alley. If they’re desperate enough, behaving strangely enough, being victimized enough, they wind up in police custody with well-meaning police officers.

Joel Lashley: Now, what do we do? Believe me, they would much rather take them to a good facility, much rather. I’ve worked in urban psychiatric facilities, and I’ve seen the squad cars pull up in front of them in the middle of the night, and let somebody out of the car, and point and say, “Go that way.” Because they were so desperate for what to do with these people, and they wanted to do the best they could for them, but they couldn’t take them home and build a cot in the garage. So, that was the best solution they were left with.

Gary Klugiewicz: But the issue is that when you do this right, and the people that do it right, do it really right, and we have to learn from those people that are doing it right right now. I’m going to tell you is that, you can just see it. A person walks into the facility, hospital, mental health facility, jail, and somebody has a smile on their face. I’m already saying, welcome. I know you don’t want to say, “Welcome to the Morton County jail,” but you are, you’re welcome. I’m not a threat.

Gary Klugiewicz: The point of matter is that explain what’s going to be happening to them. I mean, sometimes people aren’t in a place where they can understand, but just hear my tone of voice. It’s very calm. I use my tone of voice, I’m going to tell you what’s happening next. The point of the matter is, you’ve probably been a squatter for a long time. Do you have to use the bathroom? It’s right over there. Do you need a bottle of water? Get something to drink. I’m sorry. Well, you haven’t eaten for a while, those bologna sandwiches look pretty good if you haven’t eaten for awhile. You want a sandwich? I’ll get you a sandwich.

Gary Klugiewicz: Then they get processed, and whether that’s into the hospital, or whether into a jail, they processed in here. I got to take some information. Give me the information, I’ll get you going and move you along quickly. We’ll get you upstairs and get into a bed, if that’s appropriate in a jail. But the point of the matter is, if it’s a hospital, maybe we’ll get you a room so you can sit down.

Gary Klugiewicz: All those things, is how you said it. If you do a lot of non-escalation, you don’t have to do the de-escalation. If I don’t have to do the de-escalation, I don’t have to get the crisis management because we’ve drove them there. So many times, we can drove them there, drove them back. I can just tell you, the way you approach it is everything in terms of bringing it down again. They brought you down. They want to be safe, let them be safe.

Understanding the Patient Perspective to keep everyone safe

Brine Hamilton: That’s good stuff. A lot of that too is they’re simple things, but we don’t necessarily think to do them because it’s just not how we’re trained, like you said. Now, I kind of want to look at the perspective of that patient or, I guess if things go wrong, that inmate, who’s in a crisis situation, again, just so we can see their perspective. But what are some of the things that they’re experiencing in that that timeframe that you mentioned, Joel, that three to 30 days where they’re waiting for a bed? Or if they end up incarcerated instead of in a facility?

Joel Lashley: Well, we know from the studies that if they don’t have family support, and many of them that wind up in the emergency room don’t have that family support, either it’s non existent, or the family just can’t go. They’ve got other family members to care for, children to care for, job to go to. But they’re all going to go slowly down the journey.

Joel Lashley: So, if they don’t have those facilities, they wind up through their own devices, they commit suicide at higher rates, they self-medicate at higher rates. In the current environment, we have things like fentanyl floating around the street, and no end to that in sight. So, very dangerous alternatives there.

Joel Lashley: Or they wind up in police custody, and then they end up in jail. If they’re not lucky enough to wind up in a jail with a special management team, led by people like Gary Klugiewicz, who knows what’s going to happen? The studies are showing very high victimization rates, they wind up in the general population.

Joel Lashley: It’s not like people are going to care for them. Their peers aren’t going to care for them. They’re going to wind up with major recidivism, usually a re-hospitalization if they’ve had any treatment, higher rates of re-hospitalization, higher rates of recidivism, that very much parallel, but are not the same as, a sociopathic personality. Maybe even greater challenges as far as caring for themselves.

Gary Klugiewicz: You asked a question, I just want to answer is that, when you show up there, we have our frequent flyers that come back all the time, whether the hospital to jail. But if they haven’t, and this is a brand new experience, and again, they have all these stories they’ve seen, and they’ve seen One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, they’ve seen the terrible things that happen in jails, and so they are very afraid.

Gary Klugiewicz: So, if we can reassure them when they get here, that they’re going to be safe. Joel has developed a lot, the whole issues of safety statements. We’re here to keep you safe. Let us keep you safe. That by itself, they want to be safe. Very few people say, “I want to be in crisis.” No, I want to be reassured. I want to come down from this.

Gary Klugiewicz: Most of them, by the time they get, whether to the hospital or to the jail, they’ve had a very rough time already. They really, if we can just see them slow it down, and bring them all back in, they’d be much better off. Because the truth of matter is that they’re going to be here. Again, around the country, there’s more and more people that are having issues. The Coronavirus didn’t help in terms of the isolation.

Gary Klugiewicz: I have family members who work in schools. They can’t wait to get these kids back into school. Can you imagine being wild in the streets for a year and a half, and coming back and sitting in a school for eight hours a day or six hours a day? I mean, it’s major issues across the board. So, what we have to do is we have to figure out how we can approach them so when they come here, they can make a transition from there, to now, and that you can be safe here, we’re going to take care of you. I’m going to develop a relationship with you.

Gary Klugiewicz: Because one of the biggest things that, is Jane Dresser was a psychiatric nurse at Marquee County Behavioral Health, and she developed the crisis management techniques that we use throughout the state of Wisconsin. She says it’s pretty simple. We’re using all of the stuff that Joel uses to approach them and do it all, but at some point in time, you have to get their attention without setting them off more. They’re already set off. I want to get their attention without sending them off more. I want to find out their perception of reality.

Gary Klugiewicz: Now, when someone’s yelling at me in my emergency room, my first thought isn’t your reality. I’m thinking about my reality, you’re wrecking my night. But you have to think, why are they acting that way … What is their reality? What are you thinking? We always tell people, and again, I’m telling anyone who works with people they have to get close to people who are in crisis, no matter what the reason, don’t be touching people too soon and not be ready for the reaction.

Gary Klugiewicz: Because if somebody believes that you’re the devil and all his minions, do you really want to touch them at that point in time? Or would you rather know that, I think you’re the devil and all his minions. Now, we’ll deal with that. But first, I want to find their perception of reality, what they think his problem is, why they believe they’re in jail, medically, what do you believe is wrong with you? Now, we’re going to get to the reality later, but first do that.

Gary Klugiewicz: Now, just by doing the non-escalation as we approach, universal greeting and making these safety statements, and then by asking them where they’re coming from, I’m showing you respect, now I’m starting to build rapport. So, that’s the third step, is building rapport with them. Now, once I have that, it’s a lot easier to get them to go where I want to go.

Gary Klugiewicz: Now, at that time, I have to tell them my perception of reality. No, the test came back, no, you’re not having a heart attack. You’re going to have to stay here until next week to meet your court date. That’s my perception of reality. But the point is I have to bring them back to my perception of reality, and how we have to manage this, and now we can move to a resolution.

Gary Klugiewicz: But until we reach that point, it’s not going to happen. Communication is a part of all that. Without communication I can never bring him down so we can deal with them. Because the point of the matter is, we always say we want to bring them down to their baseline. Not my baseline, but their baseline. I want people back over there are our most calm, and therefore we can all be most safe. That’s who I want to bring in.

Concluding Remarks

Brine Hamilton: Absolutely. Now, we’ve covered some really, really great points here and some great learnings now. Do you guys have any final thoughts before we wrap up for today?

Gary Klugiewicz: Joel?

Joel Lashley: My final thought is, and the most important thought, is realizing that hospital emergency rooms, and police on the street are going to be interacting with people with mental health crises more than anybody else. So, they need that training. They need specific training, hospital security staff, hospital emergency room staff.

Joel Lashley: It has to be consistent across the board. I’ve given crisis intervention training to a psychiatrist because they insisted on that consistency. I had a medical college, we would give crisis intervention training to MDs, and this is how we manage our patient. You’d think that they should be teaching us, right? But they reached out because they know they needed to build that consistency, they needed a way to teach it to others. So, training is cornerstone until we’re waiting for the infrastructure.

Gary Klugiewicz: I’d like to close out with, what’s in it for me? I love that, W-I-I-F-M, what’s in it for me? Is that realize that in this day and age, no matter where you work, and something goes bad, they’re going to accuse you of wrongdoing. So, you have to always, always understand this concept we always talk about. You’re not responsible for the outcomes unless you cause them. You’re responsible for a process of trying to keep somebody as safe as you can based on what you have to do, how you have to interact with them.

Gary Klugiewicz: But again, when it’s all over, they’re going to evaluate your performance. Whether you look at the movie, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or any other thing, or any really bad YouTube video that you see of someone acting badly, is they’re going to ask you three questions.

Gary Klugiewicz: We got this from Dave Young, one of our trainers. He says very simply, they’re going to ask you, first of all, did you look professional? Now, you’re screaming and yelling at somebody, that’s not looking professional.

Gary Klugiewicz: Did you demonstrate concern, like you cared? Now, some days at the end of a rough day, there’s not a lot of caring going on in me, but I still have to act professionally, and I have to act like I care, and sometimes they have to fake it til I make it. But I have to act that way because if I don’t look like I care, I’m going to be evaluated poorly.

Gary Klugiewicz: Finally, I have to keep everyone as safe as possible under the circumstances. That’s my job. I’m in the safety business. Your safety, my safety, my organization’s safety. If I remember those things, I’ll do a better job, because remember our job is very simply is to keep everyone as safe verbally if you can, physically if you must. But our job is the safety business.

Gary Klugiewicz: No matter what we are, a teacher, whether we’re healthcare, whether you’re a police officer, we’re in the safety business, and we want to keep people safe. By doing it this way, by bringing it down, we keep everyone safer.

Brine Hamilton: That’s amazing stuff, guys. Again, Gary, Joel, always a pleasure. Thank you for making the time today, and having this important discussion.

Gary Klugiewicz: Thank you.

Joel Lashley: Thank you, Brine.

.png)

.png)