“How to Manage Intra-Organizational Conflict - Part Two ” - Episode 17

Host: Allen Oeschlaeger

Guest: Dr. Jim Bohn

On this episode, Allen Oelschlaeger is joined by Dr. Jim Bohn (https://www.linkedin.com/in/jamesbohn), a change management and leadership expert. He has decades of organizational executive experience and is the author of several books. He currently runs his own consultant practice and is a certified speaker for Vistage.

The discussion focuses on the issue of intra-organizational conflict – i.e., conflict that is internal to an organization (rather than with clients or the general public). It is the second episode of a three-part series on this topic.

Some of the core principles discussed include:

- How seemingly mundane issues can spur bigger conflicts within an organization

- Why intra-organizational conflict is actually a bigger issue within organizations than conflicts with clients or the public

- How the issues of power, turf, and fear drive a lot of conflict

- The value of having a common goal and leadership focused on driving their team towards that goal

- The role of the annual performance review

- When a new team is put together, the need to form, storm, norm, perform.

- Why leaders need to demonstrate their values, not just talk about them

To learn more from Dr. Jim Bohn, check out his books on Amazon or connect with him on LinkedIn.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Well, good Morning, Jim. Great to have you back on our show. Thanks so much for meeting here on a Saturday morning in Wisconsin.

Dr. Jim Bohn: It’s always great to talk with you Allen. Always enjoy our conversations together.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Yeah, well this will be a fun one. So, rather than me trying, why don’t you introduce yourself? So everybody knows your background and where you’re from and whatever, and then we’ll get into our topic.

Dr. Bohn's Background

Dr. Jim Bohn: Sounds great. Yeah. My name is Dr. Jim Bohn. I have an earned doctorate from the University of Wisconsin. My research skill is in organizational analysis. My specialties are change management and leadership development; also along with that, I have taught in multiple universities in the Southeast Wisconsin area, worked in a Fortune 100 company for 33 years. That would be just controls and also opened up my own consulting organization, which is PROAXIOS. I’ve written four different books in the area of change management, IT change, organizational engagement, which is a compliment to employee engagement and a book called Nuts and Bolts of Leadership. So I have a dense background over four decades of working with literally hundreds of leaders and thousands of people in multiple different ranges of markets ranging from oil and gas to banking, to retail, to telecommunications. So I don’t want to say I’ve seen it all, but I’ve seen a whole lot.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Exactly. I think we did talk Jim, about how, when you go from organization to organization, this was early in my career. There was a guy from General Electric who came to our organization and I was a new guy coming out of business school and he goes, “Allen, you’re going to have a long career. And I’ll just give you one little piece of advice.” He goes, “Nothing changes, but the part numbers.” And it’s so true, I’m sure you’ve seen the same stuff over and over and over again, no matter what organization you’ve worked with.

Dr. Jim Bohn: I had a friend who used to say, the bodies had been moved, but the tombstones are in the same place.

Allen Oelschlaeger: There we go. Yeah. So, just give that one example you’ve shared with me about when you were with Johnson Controls on how you would go into an organization and people’s jobs would change pretty dramatically. So just share that. So people get a sense for how bigger changes you dealt with.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Do you mind if I use a different one?

Allen Oelschlaeger: That’s fine. Yeah.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Well, the one Allen was referring to was in big pharma and the work that we did had to do with what we called, facilities management, and essentially what happened to those people’s jobs would move from their organization into Johnson Controls. But the one I want to share with you today is a little bit more relevant, I think, to the subject that we’re talking about. And that is the hardest change process that I ever did, which was standardizing uniforms for 5,000 people. Now that may sound very mundane and very boring. It may sound like, well, all you do is just tell them what to wear tomorrow. But the reality is that is extremely complicated because when you’re talking about people’s attire, when you’re talking about their clothing, you’re one step away from the thing that is most valuable to them in the workplace, of course, which is their pay.

So that was one very, very complicated change process. And I just recall a vice president walking past me in the hall saying, “Can you get those uniforms standardized in a couple of weeks?” And I took a breath back and I said, “No, this is going to take a little longer than that for us to do this right. I mean, we can force anything, but to get this to really be adjusted and adapted, we’re going to have to do some work.” So anyway, real quick story on that one. Of course there are people out in the field who were very, very frustrated about the idea at all.

So one of the most important things you can do in change is engage the people who are rejecting the idea. And so what I did is I contacted one guy out in Oregon and I said, “What do you think about this?” Of course, he was very brusque and [inaudible 00:04:28], “This is never going to work.” I said, “I’ll tell you what, we’ll send you a couple of different versions of this.” And the funniest thing happened. He ended up putting one of the shirts on his dog and having the dog roll around in the dirt and run around for the weekend to test the shirt, if it would hold up. And then we used him as an example on our conference call, I had him talk about what he did with his dog. And it was a great way to get people to adjust to the new idea, but we surveyed almost a thousand people. We got the responses, it sounded really simple, but it is by far the hardest change that I ever conducted.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Very, very interesting. Yeah. A few years back, I talked to an attorney who had been in private practice and then joined an organization. And he said, the biggest issue that he’s seen is who got to sit next to a window.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Yeah.

Allen Oelschlaeger: And if you move somebody into a different cubicle or office that didn’t have a window, it was… it couldn’t be any worse. Right?

Dr. Jim Bohn: Well, the interesting thing about that is that really sets the table on the subject that we’re talking about. It’s many times those mundane issues that tend to spur on bigger issues and bigger problems. So, that’s the subject we’ll be talking about, but I’m more than delighted to say that one other issue that I faced was two teams had been in the same building and one team was forced to move across the street. And I remember one team saying to me, “That road has now become the greatest obstacles of our progress.”

Allen Oelschlaeger: Wow. Yeah. Well, so people have been listening to this podcast know that I work with Vistelar and we are a conflict management training company. However, what we normally focus on are working with contact professionals, meaning anybody that’s dealing with either their clients or with the general public for most of their day. So that would be obviously police officers, teachers, healthcare workers, parking officers that are dealing with parking tickets, casino workers, hospitality workers, transit workers, anybody that’s dealing with the public or their clients regularly. Salespeople are in that category. But usually those interactions are fairly brief. It’s a few minutes, maybe 30 minutes, the length of a flight, whatever. And then you might never see that person again.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Right.

Intra-organizational Conflict

Allen Oelschlaeger: And what we want to talk about here is something we’ve been working on for a while. We’re not there yet, but we want to expand our market into what I describe as intra-organizational conflict, meaning people that are in the examples we’ve already shared here, but it’s where the people within the organization are either dealing with their boss, they’re dealing with an employee, they’re dealing with different departments, they’re interacting on issues related to budget, whatever. Where it’s inside the organization and conflict obviously arise there and it creates all kinds of problems. And Jim, you’ve had probably as much experience with this as almost anybody on the planet. So I just thought it’d be great to have a conversation. We’re in the process of putting this program together, you’re going to help us with that as we move forward. But I just thought we talked through what those issues look like and get some of your insights on how to deal with them.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Yeah. I’m really pleased to hear that someone was actually taking this on. I think Allen your organization may be one of the few that is actually looking into something bigger than just the local stuff. And I know you guys are experts at the local stuff. I have high respect for that, but intra-organizational conflict, it starts with something as simple as maybe even a four, five person team. Then it can move up to a divisional conflict between teams and organizations. And what I mean by that is, whether it’s HR, legal, manufacturing, production and sales; operations and sales is a historical area for ongoing conflict for obvious reasons.

And then it can go on to even higher levels where you have a one product division that is working against another product division, where there’s competition that’s built in for good reasons, which is to “bring the cream of the crop to the top.” But because of the notions of competition between groups and the notions of having to get things done, very, very often, people forget one crucial thing when they’re working with an organization and that is this; no matter how big the organization is and I could name some marquee companies here but I won’t, I’m talking about multi-billion dollar companies. There’s only so much to go around.

And what I mean by that, I know you know, whether it’s money, whether it’s retail facilities, or even like a window, like you talked about, whether it’s leadership competence because there’s limits to that; limits to the amount of people you have, limits of the staff. You have to put in your mind a box that says, no matter how big this company is, the market cap is still $8.6 billion and that’s it for today. It may go up a little bit, but you know what I’m talking about. And so that’s the beginning of all organizational conflict, because ultimately it reduces down into different groups, different divisions and different teams, ultimately even down into small teams, because someone’s going to ask the question; who is getting what and why? And that is sort of a perennial question across human nature, that sort of thing.

So there’s a pretty deep issue there, but the notion of organizations only have so much to go around. So that’s a starting point, that can breed conflict any day of the week. If you have 12 windows and you’ve got 14 people, somebody’s not going to get that window. And so that comes into the next issue of-

Allen Oelschlaeger: Jim, let me jump in and just this issue reminding me of a… I was clearly involved with that big corporation, actually big pharma. And every year we did the annual business plan and because they wanted to use a good process. So everybody contributed, we built it up from the ground up yada, yada, here’s what I want to do whatever. Got up to the highest levels. It was always way more money than anybody had to spend. So then it became the whole process. Okay. Now we’re going to whittle it down. Well, that’s where [inaudible 00:11:31].

And I remember we had a vice president of engineering, just brilliant guy, but he said, he goes, “I don’t understand why we just don’t say right upfront that 15% of our budget is going to engineering. Boom, go figure it out.” And I’m sure there’s organizations that work that way, but because we wanted to get everybody participating, it was, “No, we’re going to build it up from the ground up, make sure what projects you’re going to do and let’s forecast out.” But it was always a mess at the end because it was always like twice as much money as we had to spend.

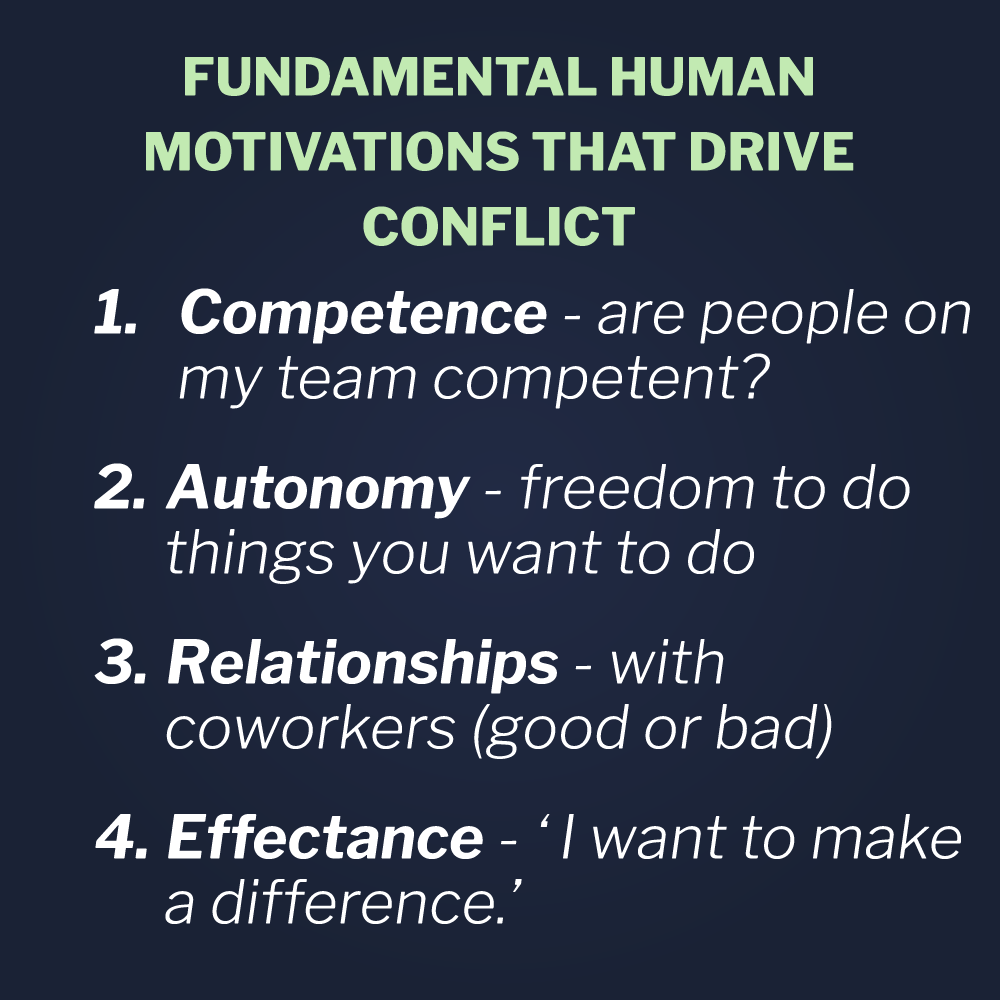

Dr. Jim Bohn: And again, that presents a bunch of new problems along the way, you’ve got too much money and now what are we going to do with the excess and so forth? So what I want to do is just take that broader sort of umbrella notion of there’s limits in an organization and put the other side of the tension out there, which is human motivation. People come to work for a lot of reasons. Primarily they come to work I believe… I’m trying to think of, there was a very famous actor that said, “I act so that I can do the things that I want to do.” It’ll come to me in a while, but there are some very fundamental human motivations that we don’t talk about a lot, but these are the ones that drive conflict and they are as follows.

Number one is competence. Are people in my team competent? Can they do the job or the incompetent am I picking up the slack for them? So just think about that one. The second one is autonomy. Autonomy is a… by the way, there’s research behind all of this stuff. I’m not going to bore you with those details, but autonomy is literally the history of the human race. It’s who’s going to be free to do something, who is not going to be free. Who’s going to resist being oppressed, who is going to rise up against it. Now in organizations, we talk about that stuff, and of course we’re much more polished in our speech, but the reality is everyone in an organization wants to have a voice and that that’s becoming more and more prominent. That started probably in the ’90s.

But in the times we live in now, especially with the power of LinkedIn and some other social media, having a voice has become almost a rallying cry for any employee that their ideas and their concepts should be brought forth and admired and such. And if you say that’s not going to happen, now you’re starting another spark of conflict because, “Well, I wasn’t respected. I don’t get the freedom to have a voice,” and so forth. That’s a really big one.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Yeah.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Go ahead.

Allen Oelschlaeger: No, just [inaudible 00:14:15]. Every time we talk, my brain goes back to my corporate life and I go, “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” I mean, it’s just universal. Go ahead.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Well, what’s interesting about that, Allen, you and I have some others storied careers, we’ve been with a lot of different people, but the same issues, even if they’re four or five decades all will keep coming up. Because again, I’ll say that human nature is consistent across time. A third real important motivation for people is the notion of relationships. People have friends in the workplace or relationships that they like to because it gives them some meaning. So if you tweak with those relationships and you move Joe Smith next to an Ann, who he doesn’t like, that’s going to start to create conflict.

And this stuff just happens naturally as you assembled teams, I’m sure that in your career, you had times where somebody said, “Allen, you’re going to work for Jim Bohn.” And you’re going, “Oh my God, that guy’s a tyrant. I don’t want to work there,” but you’re forced into this relationship circumstance; which again, so you’ve got competence, autonomy, relationships, which can be good or bad. Then we’ve got issues, real powerful one, which we don’t hear unless we ask a person, what do you want to do with your life? And they say, the following statement is, “I want to make a difference.”

And that goes back to 1958, there was a researcher called White who came up with this concept that you don’t hear very often. It’s called the effectance motivation. It’s the idea of, I want to make a difference. I want to know that I mattered and even little kids have this; they want to know that they matter, that they’re important. So if you start tweaking with that, any of those four motivations, and I can talk about efficacy and some other stuff along the way, but if you tweak with any of those, you’re going to start getting into the reasons that people come to work and that’s going to cause some problems along the way now.

don’t hear very often. It’s called the effectance motivation. It’s the idea of, I want to make a difference. I want to know that I mattered and even little kids have this; they want to know that they matter, that they’re important. So if you start tweaking with that, any of those four motivations, and I can talk about efficacy and some other stuff along the way, but if you tweak with any of those, you’re going to start getting into the reasons that people come to work and that’s going to cause some problems along the way now.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Tell me, I got to get this down. So the make a difference motivation, is called what?

Dr. Jim Bohn: Effectance; E-F-F-E-C-T-A-N-C-E and researcher’s name was a White; W-H-I-T-E. I can’t remember his first name.

Allen Oelschlaeger: No, I love it. Because I’ve never heard that term before used in that way. I’ve heard effective, not effectance, but it makes all kinds of sense. And you’re a 100% right. With all these just as you’re talking, it seems like, and you made some reference to it, but with this and I know they hate to be called millennials, but the millennials have in some of these actually more of a motivation along these lines, is there some validity of that or not?

Dr. Jim Bohn: I would say it’s the relationship piece and the autonomy piece is really, really big. And the autonomy piece, I could go into a whole soliloquy on that, I’m not going to do. But if you think about… As you and I were growing up, the notion of autonomy was somewhat limited, even by the way that our parents acted coming out of World War I, World War II, Korea, and so forth, but that has changed dramatically. And so the notion of autonomy and freedom and my voice, that’s a really, really big deal in the millennial workforce.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Yeah. Heard that.

Power, turf & Fear

Dr. Jim Bohn: So I just want to lay one more thing down before I start talking about some things that we can do to change this and to do it well. The issues of power, turf and fear; those three issues. I know you bump into this in the workshops that you do, you’re doing this just one-on-one, but the issues of power who is going to be controlling resources, that’s power. And if you’re interested in whether or not that’s an important subject, you can contact Jeffrey Pfeffer, he’s a Harvard business professor who’s spent this whole life studying the concept of power and he says things like, it’s not a question of whether or not there will be power because it will be, but it’s a question of how we will use it. It can be used for good, and it can be used for bad.

There’s issues of turf. And the place that you find this intra-organizational conflict is when people have data, for example, if they don’t want to share with other people, because it might reveal number one, that somebody was hoarding some information that’s important, or because it keeps those people in business. I’ve met people who’ve had spreadsheets they protect it with multiple passwords because they didn’t want anybody to know the cross-references for part numbers and so forth because they were the ones that knew it and they protected their jobs. So there’s a turf element there.

And then of course the last thing that causes problems in organizations is fear. And that goes in the whole change management business and what we do to manage anxiety. So those are some of the things that are important in this subject matter. And again, I could spend a lot more time on every one of them individually, but I think for today, the key to fixing some of these intra-organizational conflicts is, it takes effort. The top thing I would say is it takes effort to manage intra-organizational conflicts. And I’m not just talking about some kumbaya speech where we just say, “We’re going to work together better.”

Allen Oelschlaeger: Right. Exactly.

Dr. Jim Bohn: And again, you’ve noticed that you’ve seen these, you go down the hall, we’re going to be great together. Two doors down, people are fighting. So there’s an element of being careful not to give the employees ra ra speeches without giving them some substance behind it because people are very smart about those things. What it takes is a leadership determination, a leadership effort to say, “All right, we’re going to make things work together.” What that entails very often is getting a team of people together around a common project. And let me say that again, the greatest successes I’ve seen in getting people to work together is bringing them together around a common project. Something that they all can celebrate together when they win something where they all can stand on top of the mountain and say, we did this together. Those things tend to build a great deal of comradery and cohesion and collaboration and organizations.

The impact of good leadership on intra-organizational culture

So the first thing I would say is that, it’s effortful leadership to say, we’re going to work on this together. And that means the executives themselves need to roll up their sleeves and stay in the fray. I can think of one particular merger and acquisition I was involved in. It was massive. I mean, bigger than most people can imagine. We had a 50 person team from all over the company, different people, different groups, different divisions. And we work like crazy to do this merger and acquisition. And we worked with a company that was being acquired and we had a spectacular team, but it was led by a guy who was determined that we were going to work together. He kept a sense of humor, but a sense of expectation, a sense of this is what we’re trying to accomplish. He kept a common sense of measuring progress.

So we knew what we were doing and brought the right people together and got rid of people that weren’t working and things like that. So that notion of having… and this really fits in human nature as well, when people are either aligned against a common enemy, for example, in a war or they’re aligned on a common goal to accomplish something together, like kind of a sports team, the amount of extra motivational power you get from that is just incredible. [crosstalk 00:22:02]

Allen Oelschlaeger: Again, you’re bringing back memories. So I was involved if in the medical advice business back in the mid ’80s and this is when total quality management was a big deal, Deming was red hot, the auto industry was going through a transformation, we brought in, I don’t know if Clark and Wheelwright. Do you know those names?

Dr. Jim Bohn: The name is familiar. I can’t say that I’ve worked with them, but the name is familiar.

Allen Oelschlaeger: So Clark, I think was from Stanford and Wheelwright was from Harvard, one of the two. And they had gone over to Japan to learn how they made cars and came back. And so they were all about Deming and all that stuff. But anyway, the company I was with hired a total quality management company to come in and embed themselves to our organization was called performance excellence member. And this was… I never thought of it in these terms, but one of their biggest thing were these cross functional teams focused on a problem. And it was let’s first figure out what the big problems are in the company. Let’s get the eight step problem solving approach where the first step was, make sure what the problem is. And then they put a team together, cross functional and they gave them time then to go work that problem.

Using teamwork opportunities to reduce conflict

And I always thought of it in terms of total quality management and whatever. But what you’re saying is that probably had a secondary goal of just getting better teamwork going and less conflict.

Dr. Jim Bohn: And also it happens because of a couple things. The funny thing is when Allen starts to learn what Jim actually does, it’s like, “Wow.” You develop a little bit of respect for the fact that maybe I’ve got a skill in an area that you don’t. And the other thing is, which is even more fundamental Allen, which helps to remove some of the fear issues. I got to tell you a funny story. I worked with one large company up in Minneapolis. I won’t name the company, but you can probably figure out who they were. And I remember when I was up there, I said, “We need to get somebody from purchasing to come and talk about this particular thing.” And I was working with the engineering group and we’ve we got this purchasing guy to come down. It was one floor down. And he said, “I’ve never met you. I’ve been here for 20 years.”

Well, it’s so funny. But the reality is, is that very often we’re afraid of people that we haven’t met. And this goes back all kinds of things that you and I could spend a lot of time on, but the more you get to know somebody, the more you realize they’re just another human being like you where they’re trying to get stuff done. And when you work with them face to face, as opposed to email, you sit in a cross-functional team, all of a sudden, you may not like everything about them. They may have tuna sandwiches for lunch that you don’t particularly like, but you come to find out they’re a brilliant engineer or a brilliant HR person that can help get things done or they’re a finance person that caught something and respect develops. All of those things are byproducts of having people work together on one thing. And it’s a whole hell of a lot of fun.

We did a merger, we did in six months. We had to hit the cooling season. It was like people had just won the world series. I mean, it was amazing because we worked together. Now, that’s not to say we didn’t have some quirky issues along the way, and people get frustrated, but those things are more done at the level of conflict. You’re talking about those one-on-one things, getting people to work together around a common goal is psychologically powerful across time.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Love it. Never thought of it in those terms. And have you had any interaction or know much about Michael Cudahy and his work at micro electronics?

Dr. Jim Bohn: I’ve met him several times and I worked with him on a couple of projects that were more non-profit and beneficial, but [crosstalk 00:26:06] interesting dude.

Allen Oelschlaeger: So quite a maverick and, started Marquette back in the ’70s. I was there in the early ’90s. He was, in my opinion way ahead of his time, but when I was there and I haven’t seen this in any other company, I’m curious if you have, we had probably in the building, it was down on, whatever that… I forgot the street they were on, but anyway, in Milwaukee but they had… Tower Avenue, sorry. And they had, I’m guessing seven, 800 people in the building probably. And there was a wall down the hall where he required that every single employee had a big picture of themselves not just some little thumbnail, but a big picture on this long wall where you could go and see the person’s name that was all in alphabetical order, you could find the person, find out what department they were in and see their picture on this wall.

And it was just as a silly little thing, but it dealt with some of what you’re describing there. I mean, you’d say, “Oh yeah, well there John Smith over in purchasing. Before I meet with you, let me go look at his picture.” “Oh yeah. I’ve seen John. Oh, yeah John was at the event. Oh, I even talked to John at the last get together,” whatever. It was a big deal. And it was… I’ve never seen another company do it.

leadership methods that reduce conflict

Dr. Jim Bohn: Well, I’ve seen some companies do it but I don’t think they did it as well as him. And I think part of it was, he was a very irenic fun guy to be around very energetic. And so if he thought this was a great idea, people were going to follow that. You’re moving me right into the next element of what I suggest that we talk about as far as resolving conflict. So nice to put the ball on the tee. Leadership is one of those hackneyed overused words that candidly almost drives me nuts with that. And I look at our LinkedIn, there’s somebody writing a new leadership book every day, and then, executives go through an airport or when they pick up a book, read it and they turn their whole company upside down. But the hardball leadership, day-to-day leadership really makes a difference, when it comes to this stuff.

And I’ve seen people in top levels of organizations, come down to a level of just plain speech, no corporate talk, getting together with people in cafeterias, meeting them in lunch rooms, meeting them after work. And because of the skill sets that they had, not only interpersonally, but also because of their competence; I know people are so smart, it’s just this risk ridiculous. But they also were able to candidly just be part of working with people on a grade level. And when those kinds of people come into a team and they set an expectation for teams to work together, people know that this is not just more stuff that’s written on a wall or a PowerPoint slide. They know this person he or she really does mean to have a white hot team. It just at the risk of personal blathering, I always told teams that I came into in the beginning, even some very, very difficult one says a designated hitter. I said, “We will have a white hot team within two years, and we’re going to do great things in this company and we’re going to do them together.” Now I had to back up my words with that.

And to do that with things like taking care of their pay, making sure that people were properly recognized for the work that they did and so forth. But when you’re talking about intra-organizational conflict, nothing does a better job of fixing that than someone who’s engaged in the broader process. The one boss, I wish I could use his name but I wont, that just emulated this so much, he was all about getting the job done. He just reminded me so much of my dad who was a blue collar guy couldn’t even write, but John was brilliant, but John had a Harvard education. He was the top dog, and yet he just was all about, “Let’s get the job done.” And he wouldn’t countenance things like gossiping. He wouldn’t countenance things like let’s draw up some old story.

I mean, he would call people on old news very quickly and say, “What are we going to do to get the job done?” And eventually what happens when people hear that? They realize that that leader really is about getting the job, that they’re not there to carry a grudge. They’re not there to… which I’ll talk about in a minute. They’re not there to cause people hardship. They’re just here to say, “Okay, you’re on my team. We’re working together. We want to accomplish this big thing. How can I help you do that? And what are we doing to get the job done?” And at a very baseline level, I’m talking about mechanics and getting in trucks and all that kind of stuff makes a dramatic difference in solving team conflict.

Leadership Methods that foster conflict

Conversely,… let me get this point up. Conversely, the leader that consistently talks about how powerful their team is as opposed to somebody else in the organization and runs that other team down, all they’re doing is adding [inaudible 00:31:32]. And so those are the people that very often are setting up the organizational conflicts that you see. In fact, some of them take pride in it. I wouldn’t go so far as to say they’re narcissists, although there’s probably a percent that are, but it’s like, “We’re going to prove that we’re better than anybody else.” And as soon as you do that, you’re starting to put people in a role where they don’t feel respected and all been one of Bohn’s laws is if you push people [inaudible 00:31:58]. And so the two things I’ve mentioned so far, having a common goal and then having leaders who are willing to work with people and drive them toward the goal and to get away from some of the personality stuff, which by the way will never be fixed. I mean, there’s evidence to that. So that make makes sense so far?

Allen Oelschlaeger: It does, but there’s such a fine balance between that last point you made. That between saying, “Okay, on one hand, I want to make sure that my team knows that we’re crushing it. We’re the best on the planet. We’re doing great things for the company. We’re making a difference,” whatever, and then still not making it look like somehow we’re better than anyone else in the company.

Dr. Jim Bohn: I think there’s a way to do that. I’m just a big fan of letting reputation speak for itself, but within the team, you’re always saying, “Let’s do this. Let’s rock and roll. We’re going to be a white hot team. We’re going to do great work. We want to be known for something that’s big. We want to be respected because people want that.” But outside the team, ensuring that we’re there to help the company succeed. I always ask executives this one question when I’m in workshops with them, how easy is it to work with you?

Allen Oelschlaeger: Yeah, there we go.

Dr. Jim Bohn: And if people say, “Oh my God, I never want to work with that guy again.” I’m telling you that that is a place where conflict will start. I want to take a quick aside here to mention this notion of… one of the thing when it comes to human personality and those motivations I talked about before, I always, when I’m in workshops, asking people how they’re dealing with their teams, I asked them this one question, “Have you ever been to a class reunion?” And they look at me and they kind of laugh. Of course some have been 10 year, 15 year, “I’ll be doing my 50 year class reunion next year.” And I asked them, “What are those people like?” And they all say the same thing. “They’re exactly the same as they were in high school.”

Here’s the important point. One of the other things that causes conflict in organizations is when Allen tries to change Jim into Allen because Jim and Allen are going to be who they are. And there’s going to be a very constant over time. There’s something called a big five personality, [inaudible 00:34:22] that proves that it’s been used across hundreds of thousands of people. When organizations try to train people to be different then try to train them to act different, they’re missing the point. The point is, let’s work toward the common goal, let’s work on that together. And Allen may be a little more introverted, Jim maybe a little more extroverted, but the common goal is something both of them can approach together. So does that make sense?

Allen Oelschlaeger: It does. And I’m… and maybe this is another little aside, but I’m curious in your opinion on this, is that what you’re describing; you’re saying, okay, don’t you’re a manager, you’re not going to change that guy that you’re working with them. Either they shouldn’t be in the company, which is obviously another source of conflict, or let’s all get focused on the common goal and understand we’re bringing strengths and weaknesses to the team and let’s go figure it out. But where do annual performance reviews fall with all that? And you could probably go on for four days about that, but what’s your opinion about annual performance reviews?

The importance of "Good" Annual Performance Reviews

Dr. Jim Bohn: Oh, I know that there’s a big push to get rid of them, but I candidly believe that an annual performance review is a very valuable tool if it’s done right.

Allen Oelschlaeger: There we go. Yeah.

Dr. Jim Bohn: If only a punitive action to bring up all the terrible things I've done in the past year, don’t do it. But if you use a performance review in a good way and let that person bring their PR, bring their achievements forward, bring forward the things that they’ve accomplished, bring forward how they’ve benefited the organization. The powerful sub current of that is a person gets to go back and get to what, remember? “I want to make a difference.” And so they find that out and the person that’s leading them says, “Man, you really have made a difference this year.” And when you think about it and people’s lifetime, they spend a third of their lives at work. They want to know they made a difference and if annual performance review can do that… if an annual performance review is only to bring up nasty stuff that happened five months ago, that’s like me and my wife fighting about something that happened 20 years ago. It’s just silly. And it goes nowhere.

And so the tricky hard things should be addressed immediately. And I’m sure you feel the same way. It’s like, you know what? You have to align, let’s get this done. But the performance review, I think, should be to say, we’ve accomplished a lot together this year, let’s set some goals. I never saw them as bad things, unless they were just some sort of punitive action to get rid of somebody in the organization, but that’s not the way to think about it. And I think that that’s probably why somebody along the way had a bad performance review. And so they color everything in there, every performance you’ve ever have is something bad. And no one has a right to review my performance, but the reality is organizations pay people to do work. And if you’re not doing the work there’s always something we can improve on. The greatest managers I ever had said, “You know what you do to all this great stuff. Here’s two things. I really think you got to work on Jim.”

Allen Oelschlaeger: Yeah, there we go.

Dr. Jim Bohn: And because I respected them. And because they had challenged me throughout the year, it was like, “You know what? Oh my God, I didn’t even think about that.” And so I got better. There’s one other element that I touched on it just a little bit. And that’s the notion of executives that don’t hold grudges. The ones that hold grudges will tend to continually build intra-organizational conflict. And what I mean by that is that if Allen doesn’t like Jim, and we hold onto that grudge, that can just… people know about it, they pick it up, they know it’s not on the grapevine.

But I had one boss one time I did the terrible, terrible thing with a project I was working on an insight, skipped a step and caused him some serious, serious pain. I mean, serious pain. And he took me into his office that afternoon and he let me have it and he was right. What I had done was inexcusable. That night at the Christmas party, he saw me, shook my hand, wished me a Merry Christmas, introduced me to his wife, big smile on his face like nothing had happened.

Allen Oelschlaeger: We’re moving on exactly.

Dr. Jim Bohn: We’re moving on. “Jim, you really screwed up and it costs me dearly and you’re going to go fix that right now,” which I did. But I expected for sure when I saw him that night that I have to hang my head down, it was always like that. It was like, “No, we’ve taken care of that.” And I think that’s a big piece of… if you have executives that hold onto those grudges, that builds intra-organizational conflict too. So, the last-

Allen Oelschlaeger: Two quick things, what is… I’m sure you’ve… and I’m sure you have no data on it, but your question of if performance reviews are done right. I think the big issue here is what percentage of performance reviews are done right. And I think there’s a lot that aren’t done right. And they do what you’re describing. Basically it’s an opportunity to beat somebody up for what they did over the last year and eight months ago and whatever. But to your other point is, I’m sure you’ve heard the story. I think it’s a Watson at IBM. And I don’t know if it’s even a true story, but where the guy walks in and he had made some mistake that cost the company $10 million. Did you hear that story? And he came in expecting to get fired and Watson, “Fire you? I’ve just spent $10 million training you.”

Dr. Jim Bohn: I have heard that. I think that was [inaudible 00:39:46] in one of their leadership books.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Yeah.

To be successful, Don't focus on differences

Dr. Jim Bohn: So I’ve got one other thing that I think helps to resolve these conflicts and bring things toward more normalcy in organizations. And I mean, clearly right now, there’s other conflicts that are going on that… I’m just going to express this. I think we’re so focused now on our differences in organizations, and I’m not going to go into all the details on that. We’re so focused on our differences in organizations, especially in HR, that we are losing sight of the things we’re doing together. And that’s why I would always tell people, I don’t care where you came from. I don’t care what your background is. I don’t care what part of the world you kind of came from, or what your beliefs are, any of that. That’s great. That belongs to you. That’s what makes your identity. What I’m interested in, is that you have a skill and you have a persona and you have intelligence that can build this team. That’s all I want. That’s all we need. And let’s focus on that. But I think again, we’re focusing so exclusively, more and more exclusively on these finite slivers of difference that it’s really getting harder and harder for people to say we have things in common as opposed to the things that we have are different. And that’s just sort of an editorial.

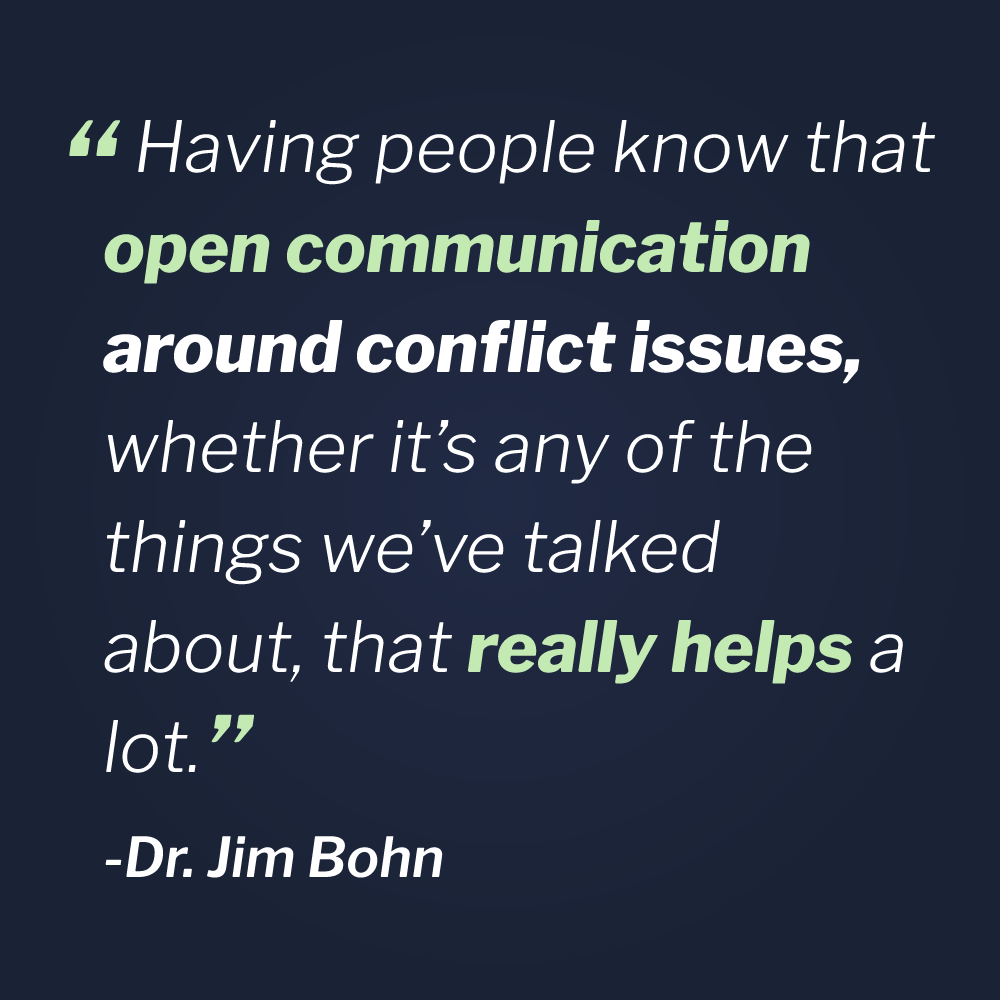

So I want to give one last bit on this, in the big projects that I was talking about, getting people together, in a room together and having them talk about the conflict issues that they’re facing. It goes a long way for fixing things. Let me tell you about what I mean. One of the IT projects that I was engaged in, there were 35 different teams across an organization that were involved in this. It was massive as you can expect. And I know you were involved with some of that stuff too. Everything from data cleansing, to the coding, to how people are going to get trained, to how people are going to get affected. I mean, it was hard. So instead of just letting this sort of free fall and have people get frustrated and start to build the rumor [inaudible 00:41:58].

I got those people into a room at least once a month, while we were going through the early parts of the project, later on twice a month, where we could raise issues in the presence of each other and facilitate the group, get the issues resolved so that people could walk away and say, “Okay, now I know what I’m doing.” And it’s sort of this buildup that needs to get resolved. And once that happens, two things occur. Number one, okay we know the next step in this. And secondly, it was like, okay, we’re going to have a rhythm and routine here where we’re going to come back together and talk about this. And maybe we’ll get to it earlier if we need to get through it sooner. But having people know that open communication around conflict issues, whether it’s any of the things we’ve talked about, that really helps a lot.

project, later on twice a month, where we could raise issues in the presence of each other and facilitate the group, get the issues resolved so that people could walk away and say, “Okay, now I know what I’m doing.” And it’s sort of this buildup that needs to get resolved. And once that happens, two things occur. Number one, okay we know the next step in this. And secondly, it was like, okay, we’re going to have a rhythm and routine here where we’re going to come back together and talk about this. And maybe we’ll get to it earlier if we need to get through it sooner. But having people know that open communication around conflict issues, whether it’s any of the things we’ve talked about, that really helps a lot.

When it comes down to the issues of power and turf and fear, those issues again are best addressed one-on-one by leaders working with the people that are manifesting those things; that’s different than looking at the… for lack of a better word, the collective per se, but getting people up to focus on what we’re accomplishing together, ensuring they get a chance to communicate about it, get a chance to even belly ache about it, complain about it and to address it continued to move things forward. I’ve seen that work, I would say, 80 to 85% of the time.

Allen Oelschlaeger: So you might know the source of this. I don’t know how many, years and years and years ago, I heard some story, probably heard it at a conference or something. I don’t know the source, but it was a… and I’m sure I don’t know who it was, but it was this idea of relative to a team is form storm, norm, perform.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Yes. That’s forming, storming, norming, performing, what’s that guy’s name? He came up with it probably in the late ’60s. It’ll come to me as I’m going along. But he developed this, those are the stages of performance in the team. I want to say Hathaway, but that’s not the name but it does start with an H, it’ll comes to me later on.

Allen Oelschlaeger: It’s from the ’60s so it’s not that long ago. So yeah.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Oh, yeah.

Allen Oelschlaeger: That’s what you’re describing here. You’re getting a team together and you’re saying, performing and storming is that opportunity to bellyache and communicate and what are our issues and let’s work through them. And then you finally get back to, okay, now we finally have a chance to get back to normal where a lot of that stuff’s been working, we’ve worked through it. And then ultimately, now we can finally perform and really make some great stuff happen.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Right. And the reality is that that cycle may happen 12 or 15 times within a long project.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Really

Dr. Jim Bohn: Yeah, it’s going to happen. Especially as you introduce new members or you remove members, it’s going to happen. People need to… it’s no different than any good communication processes. Son of a gun. I didn’t like this with this habit, it gets addressed quickly. You figure it out, we address it. And then when people are working together, they will go through that multiple times. Now, the trust will build more and more as the team goes along.

Good Leaders are good Role Models

The last bit I would say above all this is, leaders need to develop a way to communicate this daily. And what I mean by that, I’ve mentioned that the last time we talked is, if leaders don’t somehow demonstrate this in the work that they do. And I’m talking top leadership and there’s research that shows this. Top leadership has an influence on the effectiveness of the organization, because people are smart enough to say, “Jim and Allen aren’t getting along very well. And we know it, we see them, we hear about their teams, why the hell should I work together if those guys can’t do it?” And that doesn’t mean they’re always going to agree, then there won’t be that there isn’t some hardship along the way. But solving issues quickly and working together at the top of the organization, it’s just a fundamental of human nature.

People are watching the leaders, what their leaders do, and if they do it through that, well, it definitely has a long long-term impact. So the overall, I would say with all this intra-organizationally, there’s more to be done on this clearly. There’s a lot of action behind each one of these points. Is that bringing people together takes effort. It does not happen without some strenuous sweat bearing effort. It takes hard work and it takes persistence as well.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Well, I think you’ve said it a few times during our time together here about how it’s not some mantra on the wall. And I know you’ve spent a lot of time in manufacturing. So how many signs have you seen of the poster where it says, “There’s no, I in teamwork.”

Dr. Jim Bohn: People laugh at that stuff because they… These are things that you use in kindergarten. I’m not even sure if the kindergartners quite get that, but I see stuff like that all the time on our LinkedIn. It’s like, yeah, we know all about it… it becomes cliché. It becomes silly. And then it loses… Clearly we know there’s a value in that statement, but it needs to be done at the executive level.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Well, yeah, people need to see it, not just read it. They've got to see it demonstrated every single day.

Dr. Jim Bohn: [crosstalk 00:47:40].

Allen Oelschlaeger: And to your point about how people just know, I still remember. I mean, I was once the chief operating officer in a meeting company years and years ago. And there was some issue that got brought up that impacted another department. And the chief operating officer says, “Oh yeah, well, let me go talk to John,” or whatever his name was. “I have a really good relationship and I’ll get this addressed.” And everybody in the room, we just looked at each other because everybody knew that they hated each other.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Right.

Allen Oelschlaeger: This is just silliness, but that’s a… yeah. And not a secret. No. I mean, and it wasn’t like two people knew, everybody knew. Right?

Dr. Jim Bohn: Yeah. And it’s because the stuff gets out on the grapevine, for sure. So I’m pretty much at this point I have covered the primary areas I was going to cover today.

Concluding Remarks

Allen Oelschlaeger: Jim, this was great. I’m really looking forward to working with you as we move forward on this initiative. Obviously, it’s my personal opinion that it’s actually the bigger issue. I’ve told this story. I think you’ve probably heard it before, but I’ll do it really quick. I was in front of 500 state tax collectors and ask them where their sources of conflict came from. And I just assumed it would be in dealing with their clients, they are collecting taxes and shutting businesses down and putting yellow tape around businesses that weren’t paying their taxes and getting the police to show up and on and on. And 500 people, I asked them the question I said, “Okay, let’s contact. You've got your clients who you’re trying to collect taxes from. You've got your employees, that you’re a… because most of these people were managers. You've got between departments and every…” I don’t know, everybody. It’s hard to tell if everybody raised their hand, but a large majority raised their hand and said it was between department conflict was their greatest source.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Oh sure. Oh yeah. There was a guy years ago and the Harvard business review article, I can’t remember his name, but they wrote an article called the white space between the groups. That was the big area where all of a sudden, [Allen’s 00:49:59] got this thing and he’s doing a great illegal, but fails to hand it off to HR properly. And that kind of handoff stuff is critical. I do want to mention this. I was okay. I do want to mention my latest book on the subject that we’re talking about, which is called if your water cooler could talk. And that is about how employees see their organizations working together. It’s the employee viewpoint of whether or not we know where we’re going. Can we work together? Do we communicate? Are we held accountable for the work we do? And are we persistent together? As opposed to just focusing on the individual. So you can get that on Amazon.

Allen Oelschlaeger: And Jim I’ll put that link in the show notes for this, but otherwise, if… obviously people know how to get ahold of me, but if somebody that’s listening, wanted to talk directly to you or interact with you, how would they do that?

Dr. Jim Bohn: Best way to be to go to my website, and there’s a place on there where you can contact me through there.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Perfect. And you have four books and I’m assuming if they… I don’t know how many Dr. Jim Bohn there are on Amazon, but if… Do you know if they put in Dr. Jim Bohn on Amazon, in your books profile?

Dr. Jim Bohn: Maybe Jim Bohn PhD. I’m not sure, but yeah, you can follow me out there. And in fact at the bottom of the email that I will send you, you can see my author site on Amazon.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Oh, there we go. Oh, cool. I’ll include that too. Sometimes there’s not many Allen Oelschlaeger, so… right. But sometimes there’s… Actually, there is a Maxwell Oelschlaeger that’s written a bunch of books on some completely different area. So he pops up. I’m not sure where he’s from, but Maxwell Oelschlaeger, big guy out there with the same spelling of my last name.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Well, It’s an unforgettable name. I find that just absolutely fun to say. That’s great.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Well, it’s fun to say when you’re living in Wisconsin, but I’ll tell you, living Philadelphia, Moscow, Seattle, other parts of the country, they just roll their eyes. Yeah, Wisconsin we have a big German population here and people get the basics of how a German word is said.

Dr. Jim Bohn: You bet.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Yeah.

Dr. Jim Bohn: Well, thank you for the opportunity. I’ve enjoyed this.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Thank you so much. And we’ll hopefully, maybe talk again soon.

Dr. Jim Bohn: I look forward to it.

Allen Oelschlaeger: Take care. Bye-bye.

Dr. Jim Bohn: You too, sir.

.png)

.png)