“Seven Common Challenges Teachers Face—Part Two” - Episode 12

Host: Al Oeschlaeger, Vistelar

Guest: Gerard O’Dea, Dynamis

Subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Google Play or YouTube.

Gerard O’Dea from Dynamis Training in the UK joins us again on the podcast today to continue to talk about the decisive moment when school staff must decide if they need to take physical action when faced with conflict. In our 8th episode, Gerard shared the seven most common scenarios when this decision must be made. In this episode. In this episode, he provides a more detailed description of each of these scenarios and discusses the approach he uses to train staff to effectively deal with these situations. We learned a lot and we’re sure you will also. We will definitely be getting Gerard on future episodes.

Al: Welcome to another episode of Confidence in Conflict, your destination for learning how to prevent and better manage conflict in both your professional and your personal lives. Well, we’re on a bit of a roll here with our UK partners, Dynamis. One is a … understand I got the pronunciation wrong. I’ve been calling them Dynamis, but I learned today, you’ll hear on the interview that it’s Dynamis. I think early January, we had an episode with Gerard O’Dea, who is one of the owners, or the owner of Dynamis. Then last week we had an interview with Alex Hunter, which is one of Dynamis’s trainers.

Al: At the end of the Gerard interview, if you listen to it, we talked about getting back together to finish our discussion, and we finally made that happen. Every time I talk to Gerard, I learn a great deal about conflict management, and this interview is no exception. Listen up, this is really a good one. Good evening Gerard. Welcome back.

Gerard O’Dea: Good evening Al. Great to be here again. Thanks for asking me.

Al: Yep. For the listeners that maybe didn’t hear our discussion, what a couple … three weeks ago, is we talked … Gerard is from the UK, and is with a company called Dynamis. I think I’ve been saying this wrong Gerard. What’s the official pronunciation?

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, we get a couple different [inaudible 00:01:39] from the founders mouth, it’s Dynamis.

Al: Dynamis. I got to change that.

Gerard O’Dea: Right.

Al: Because I’m pretty sure I’ve been saying it wrong, yes.

Gerard O’Dea: That’s okay.

Al: We had a great conversation about dealing with conflict in schools. We ended that with a list of the kind of problems you see. We were going to expand on that in another call. I do want to just spend a minute, you moved here recently from close to London up to some other part of the UK.

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah. We had a fantastic opportunity come up for my wife who’s involved in the education sector. She was offered a new post in a place called the Lake District in the UK. We have moved about 300 miles north from London up to the Lake District. I think it’s the least populated part of the UK as a county. It’s very wild and sparse place with hills and lakes and lots of weather. But it’s a beautiful place. We’ve got three kids. We’ve taken the opportunity to help them to grow up in a very natural and wild place and amongst a great community up in Penrith. We’ve been there about three weeks now. We’re really enjoying it so far.

Al: Well any place called the Lake Country must be pretty nice, right?

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, it’s true. The only problem with the Lake District that the lake has to come from somewhere, and the lakes come from plenty of rain. So you have to get used to the weather up there.

Al: There we go.

Gerard O’Dea: It rains quite a bit.

Al: I think you know I grew up in Seattle. We’ve talked about how the UK and the Seattle area have a similar weather pattern. So yeah, I grew up in that.

Gerard O’Dea: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yes. Yeah.

Al: It’s not-

Gerard O’Dea: You just bring an umbrella with you everywhere.

Al: It’s not hard rain. It’s not like pouring rain, it’s more drizzle rain, is that right?

Gerard O’Dea: I think we get every kind of rain. Sometimes it rains for days, and sometimes it just rains for five minutes. Recently of course, we had this huge storm, storm Keira that just came across the UK and it’s basically been blowing a gale for several days, and raining as well. I don’t know, we’re going to see how it turns out. But I’m spending a lot of time on various online sights looking for waterproof clothing and rain-proof accessories and things like that. That gives you a little flavor as to where I’m at.

Al: Yep. Yep. I think that was the joke in Seattle. If you’re in Seattle, there’s Mount Rainier, right? Which you can see from Seattle, and the joke always was, in terms of the weather, is that, if you can’t see Mount Rainier, it’s raining, and if you can see it, then that means it’s going to rain, yeah. Pretty much the plan. Anyway, you told me that you’re actually down south of where you live, and you’re in a … you’re close to Stonehenge, which is very cool.

Gerard O’Dea: Yes, so I’m on a training assignment right now. We’re actually visiting one of our clients at Great Western Hospital in Swindon. We do work for Circo Health. Circo is a big government services organization that work globally. In the UK they have numerous hospitals that they manage facilities for including security. We’ve been involved with them for about two years now, and helping their security teams to kind of baseline their approach to patient and visitor interactions, how to deal with their more high-stakes encounters. And of course then the natural progression is how to deal with the physical encounters that they have in the hospital setting with people who are very distressed or being violent.

Gerard O’Dea: I’m here in Swindon. I’m staying at a very unusual hotel that has a kind of Japanese theme in terms of it has Japanese signage everywhere, and it has a Japanese library upstairs. They have a fantastic Japanese restaurant. I think it must have something to do with the big Honda Motors factory or assembly plant that’s just down the road.

Al: Oh cool.

Gerard O’Dea: They must have some Japanese engineers who visit and who like a little bit of a taste of home. So it’s really interesting to stay here.

Al: You know a little Japanese. How many years were you in Japan?

Gerard O’Dea: I lived in Japan for about four years many, many years ago. I studied Japanese at university and spent some time at university there. Then I lived in Tokyo for about four years.

Al: Oh, cool. Yeah, yeah.

Gerard O’Dea: Seems like a long time ago now.

Al: You don’t know what a long time ago is yet Gerard. As you get older, a long time means different things.

Gerard O’Dea: Thank you Al.

The Seven Challenges Teachers Face

Al: Little younger than me. Let’s look back to what we talked about last time, we had the … You identified the seven issues, or whatever, how you ever described them. Why don’t you review that real quickly, and let’s get into what you do to address those.

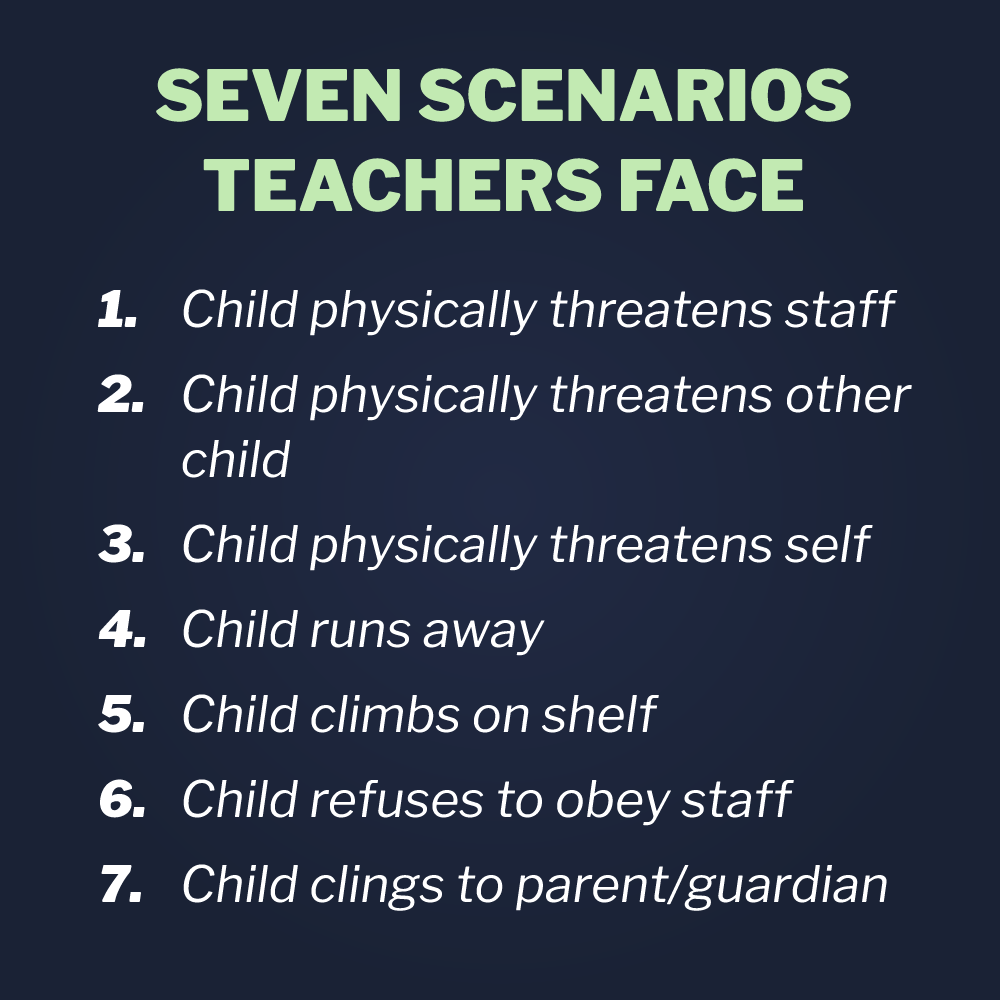

Gerard O’Dea: We use a framework to describe what we understand to be the seven key scenarios that school staff face when it comes to making a decision, whether to put their hands on a child or not in a given school day let’s say. Now most school staff don’t have to make this decision very often, but you have various teaching assistants who are maybe on a one-to-one relationship with a child, or you have deputy-head teachers whose job is inclusion, or you have SENCOs which are special educational needs coordinators, and those people sometimes have students at their schools who display violent behaviors. We use a framework of seven scenarios that when the decisive moment arrives, you’re probably in one of those seven scenarios, that’s how we do it. That’s what we talked about last time.

staff face when it comes to making a decision, whether to put their hands on a child or not in a given school day let’s say. Now most school staff don’t have to make this decision very often, but you have various teaching assistants who are maybe on a one-to-one relationship with a child, or you have deputy-head teachers whose job is inclusion, or you have SENCOs which are special educational needs coordinators, and those people sometimes have students at their schools who display violent behaviors. We use a framework of seven scenarios that when the decisive moment arrives, you’re probably in one of those seven scenarios, that’s how we do it. That’s what we talked about last time.

Gerard O’Dea: The first three scenarios have to do with direct violence. Number one, two, and three are the child is so upset, distressed, and frustrated that they might hurt, or they’re going to, or they look like they’re going to hurt a member of staff, that’s one. Number two is another child, they might hurt another child by lashing out at another child near them. Number three is that they’re so distressed and upset that they actually might turn that violence against themselves and try and hurt themselves in a scenario we call self-injury.

Gerard O’Dea: Then we look at pretty much every school that we’ve ever visited, they have a report of students who might try to run out of their classroom, or run out of the school building. And indeed, some pupils who are in that state will try and leave school altogether and go off premises. That’s a particular issue in primary education let’s say, because the risk of a young child out abroad in the community unsupervised is really quite high. We call that absconding, or a runner, a child who’s running away, that’s number four.

Gerard O’Dea: Number five is different to the first four in that we say, number five is a child who’s not necessarily upset, frustrated, or distressed, in fact they might just be having so much fun that they forgotten to be safe. That’s the child … the joke there is that the child who you turn your back on them for a moment and they’re doing a merry jig, dancing a merry jig on top of a bookcase that they’ve climbed up on.

Al: Exactly.

Gerard O’Dea: Number six is a child who then isn’t being directly violent or aggressive, but they have resisted a request of staff, which is being disruptive, and not just a little bit disruptive, but it’s being significantly disruptive to the learning task that the teacher or the educators are trying to achieve in that classroom. Usually in most environments the educator will want that child to leave the classroom so that their disruption isn’t affecting all the other pupils learning. That sometimes can make the teacher face a decision whether to prompt the child to leave the classroom for example. That can then develop, but that’s number six.

Gerard O’Dea: Number seven was like the most recent addition to the list, where we saw some teachers being prosecuted in the courts here for using force with a child early in the morning when the child wouldn’t separate from their parent, and there was a request for the staff for help, and then things got complicated, and the parent wasn’t happy with how the situation was dealt with. We call that last one separation in the morning.

Gerard O’Dea: To recap, you have broadly speaking, these seven scenarios where it’s violence to staff, violence to another child, violence to the child themselves, a child running away, a child exhibiting risky behavior, a child who’s being extremely, we call it significantly disruptive, or a child who is experiencing separation issues in the morning, and those are the seven we use.

Al: What would you say … Obviously the ones that are the most concerning are the first three, because there’s potential harm, or harm in process, but what have you heard or you experienced with the most frequent? What do you hear the most, where the people go, “Oh yeah, this happens all the time?”

Gerard O’Dea: I think it changes between primary education and secondary education I have to say. What we tend to find, and this is anecdotal, is that in primary education we find that staff are the brunt of the violence when it does happen. Primary-age children tend to direct their lashing out, or kicking, or spitting, or biting, whatever it is, against the staff who are dealing with them. That seems to be the most obvious and most frequent that we are told about when we visit the schools. It’s often the reason we get called, by the way … so often what sustains our business throughout the school-year, is the emergency calls that we get from schools who, if school starts on the fourth of September, we’re getting calls two, three weeks later from very persistent management saying, “When can you get here to help my staff?”

Al: Oh wow.

Gerard O’Dea: What that means, they’ve all arrived in after the summer break, there’s some new children in the class, there’s some children who’ve moved school and so on, and maybe the child’s paperwork didn’t follow them, which of course is a massive issue, so the teaching staff are dealing with an unknown quantity so to speak. Maybe the child isn’t settling in so well. One day they have an explosive event, and then the next day they have another one, and a week later they have another one, and all of a sudden they’re realizing that they’re not quite equipped to deal with what’s happening.

Al: Your point being-

Gerard O’Dea: To give you a-

Al: … that’s more on … the staff harm is more on the primary school side, is that what you said earlier?

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah. That’s absolutely true. What we see in secondary then is that the children in secondary school tend to understand that if they do hurt a member of teaching staff, if they lose control of themselves in a moment where they’re very distressed and they actually direct that towards a member of staff and they hurt a member of staff, most secondary children know that that’s going to invoke some very serious consequences. That just tends not to happen. What we do see in the secondary environment though is that all kinds of status and hierarchy issues and cliques and relationships kind of come into play. You can have pupil-on-pupil violence happen where the pupils aren’t really able to control themselves the same way as if it was a member of staff they were upset with. As you know Al, the bystander effect in terms of conflict, the bystander effect is that if the bystanders are watching me, then what I’m feeling in this scenario is 10x.

Al: Right.

Gerard O’Dea: What I mean is, if everybody’s watching me being disrespected or everybody’s watching me being made a fool of in front of my peers, then it’s very hard for a teenage brain to control that. In the secondary environment we see … we get asked if you like, to help the teams to make the decisions around breaking up fights.

Al: Yep. Got it.

Gerard O’Dea: That’s the clearest, probably most popular example that we have. That by itself is just fraught with difficulty and really good decisions need to be made. Maybe we can circle back to that later on. But those are the most popular, I think in terms of seven scenarios.

Al: Popular in terms of driving a request for your training, is that the best way to-

Gerard O’Dea: I think so. Yeah, I think that’s an accurate portrayal of it.

Al: I think I mentioned we were down in a school district here near Milwaukee, and we talked about these seven things, and we’d never really organized our thinking in this form, but it was very helpful. Because we were talking about the specific methods we would be teaching, and a lot of times you get into the specific method, and it’s just … you don’t have an application for it. It’s like, well I’m going to teach you a how to escape from a choke, well, that’s … I just … after listening to you, I go, “It’s got to be much better to put that in context as to, you know, what are we dealing with here,” in terms of it … on a staff member, whatever.

Al: Anyway, the feedback we got is similar to what you described here. There was both principals from elementary schools and high schools and middle schools in the room. It’s for a whole school district we’re doing here, so it’s the entire school district. But when we showed them the list, the thing that came up the most in terms of frequency, not necessarily what would drive them to call us, they’ve already called us, we’re already going to do some training there, but they said the most frequent thing is the runner, right? Is the kid that’s running, just running, running outside, running away, running out the door, and not … and the teachers just not having any idea what to do, right? Should they get in their way? Should they play goalie? Should they put an arm out? What should they do in terms of …

Gerard O’Dea: Well that’s really interesting. It’s really interesting. I think it does mirror what we hear here. My joke about that, sort of flippant comment that I make on almost every training course is that every school in England that I’ve ever visited has what they call the runners. In terms of the frequency, you’re absolutely right, but the problem with running, children running, is that they can run much faster than the adults.

Al: Right. Right. Yep.

Gerard O’Dea: They’re smaller. They’re fitter. They have less joint issues. Generally speaking, they can just run. One of the strengths I think of our training approach here in the UK, because of the regulatory environment that we work in and so on, is that we have to risk-assess every recommendation that we make. If we were to say, and it would be nonsense, but if we were to say that staff had to run after these children, the risk-assessment around that would then mandate certain fitness requirements and we’d have to go in the sports center and do sprint tests and make sure that everybody was up to standards. It would start to sound very ridiculous very quickly.

Gerard O’Dea: Of course, we’re not going to be running after children. That sort of begs the question then, well what are we going to do? We have to then make our way around the problem and make sensible precautions and sensible advice for staff. I also think there’s an interesting behavioral issue with the running. When I talk to my friend Sarah Naish about this, who runs the National Associations for Therapeutic Parenting here in the UK, and they help lots of foster parents and adopters who have … they look after children who probably have some kind of trauma in their history. Sarah’s approach to this idea of running is really interesting, because she said, “Look, if the child is so dysregulated and upset that they absolutely want to get out of the room that you’ve put them in, then you should open the door, step aside, and let them run.”

Gerard O’Dea: Because if you don’t, then the escalation that they’re feeling, the arousal, the panic, the survival instinct that has kicked in, that means they want to run out of the room, that’s only going to be, if you like, pressurized and contained, if you shut the door, or you play goalie, I love that phrase by the way, I love the image that comes to mind of playing goalie. But I thought it was a really interesting perspective is that sometimes when we try and contain a behavior, we’re really not listening to the thing that’s driving it.

Gerard O’Dea: If the child’s behavior says, “I need to get out of here right now,” then I would encourage staff to really listen to that and to, as we say in Vistelar, to try and see that perspective and acknowledge it and then anticipate the needs that are driving the behavior, it’s really important.

Al: We only had a chance in this meeting for a couple of examples, but that was, what you’re describing is exactly what happened. If I pictured it right, you had a hallway, kid is running down the hallway like crazy, and there was a teacher in a head of the student, and kind of played goalie and ended up kind of having the kid try to run between the teacher and the lockers, right? And then the teacher moves over, puts their arm … try to stop the kid, and it just gets crazy, right? I don’t know what happened afterwards, but they said it escalated from there. It was kind of a mess. The kind of [crosstalk 00:21:14]

Gerard O’Dea: But I think one of the things about our seven scenarios is that it makes those things predictable, and then we can drill into them in the training sessions and say, “Right, what’s a good idea here?” Or, “What are the risks?” What is your job as a teaching assistant, or learning support, or teacher, or classroom teacher in that scenario? Because we’ve identified the scenario, we can then talk about it in the training. I think that’s so valuable for people.

Deciding on the Best Course of Action for the Situation

Al: By the end of the meeting, probably the biggest issue was that, and these again, these were mostly principals, there was some student services people in the room and whatever, but it was mostly principals, associate principals. They said, “The biggest question we get as a principal, I get called by teacher and they say, ‘What we do in this case?'” And the principal appropriately so says, “Well, it kind of depends. How well do you know the kid? What’s the kids’ background? What’s their history? What’s the circumstances? What’s happening otherwise? Where are they running to?” Whatever it is, and he goes, “It’s just not satisfactory to the teacher. They want to know what the rules are.”

Al: It’s really hard to write hard and fast rules in these situations, right? Does that come up? How do you deal with that? Because as we know, Gary [inaudible 00:22:44]

Gerard O’Dea: I think so. We do come across people who … yeah.

Al: Well I was just going to say that it’s the totality of the circumstances obviously. It’s always [inaudible 00:22:53]

Gerard O’Dea: Sorry, Al, go ahead.

Al: It’s always going to depend, right? For a teacher, they’re going, “Well, okay, I understand, but help me make a decision, because I don’t know what to do.” I’m assuming that comes up over there. How do you deal with, “It depends,” as the answer? And then they go … Yeah.

Gerard O’Dea: Absolutely. I think we do have a lot of people, and I think this crosses over between all the different sectors that we work in. I mean, here in the UK, we as a company work in security for hospitals, we work in education heavily, but in different parts of education, primary, secondary, and special schools, for example, or mainstream and special schools, then we work dementia-care homes, then we work in for areas. I think this problem comes up in lots of different areas. I would call it, give me an easy answer.

Al: Right. Exactly. Yep.

Gerard O’Dea: Here we’re dealing with people who have lots on their plate. I mean a teacher, to be fair, their job is to deliver the curriculum, set tests, assess their students’ progress, that’s what they’re trained to do at university, that’s where they get all of their training. They don’t really, especially in the UK, I think it’s acknowledged that teachers don’t get a great deal of behavior management training to start with. So when they call somebody up, they call up behavior support team, for example, a local authority, they’re looking for somebody to come in and say, “Oh, I’ve got it. I’m the specialist, here’s a ready answer to your problem.” Unfortunately, while I totally accept why somebody would do that, I think it’s such a difficult thing for us to produce, which is a simple answer to what is ultimately a very complex problem.

Gerard O’Dea: I think we need to just educate people that this isn’t going to be an easy answer, you are going to have to apply your judgment skills, instincts, knowledge of the child as you see them every day in your classroom, and perhaps even engage with other professionals and the parents to find out what’s going on here. That’s quite a complex series of events that need to happen and lots of discussions and meetings to find out what’s driving the child’s behavior. I’m afraid that that would be my answer. What we can help people with is at the point of impact, and that’s of course a terminology we’ve picked up from Vistelar, at the point of impact, when the person needs to make that decision about what to do, then we have this decision-making framework that I spoke about in the last podcast, which has to do with the legal requirements for whether or not a person should put their hands on the child.

Gerard O’Dea: We do work on that in the training. We very seriously deal with the needs of staff to understand that there is a legal framework in place for that, and they must really carefully consider whether they need to put their hands on that child or not. Yes, so that would be the beginning of my answer.

Al: I think there’s a … just in listening to you and when we were over there in the … during our nine days together, that there’s the legal framework on what’s allowed or not allowed, and obviously they need to understand that, but then there’s still this judgment thing. I think, it sounds like you do a great job of getting people just to think about what are the issues that I need to consider? Like your example of taking the perspective of the child that’s running, right? You got a choice to make, but if you think of it from a certain viewpoint, you’re going to maybe make a different decision than if you think that your job is to make sure no kid gets outside the school, and you got to do whatever it takes to get there. I think there’s some fundamental, I don’t know what you’d call it, what would you say? Just kind of just decision-process? Empathy?

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, there’s some fundamental values [crosstalk 00:27:00] well every decision that a person makes would be based on their value-system. I have to say we do provoke our team sometimes with value-judgment questions. For example, I think I mentioned in the last podcast, or least I’ve been talking with somebody recently about the fact that if a child was about to step off a road in front of a bus, then even if the school has a no contact policy, or a no touch policy, pretty much every born and bred and dyed in the wool educator at that school would grab that child and pull them off the road so that they don’t get hit by the bus.

Al: Right.

Gerard O’Dea: That’s a natural decision that almost everybody would make, and it’s the right one, and yet it’s not based necessarily on a complex decision-making framework. It’s just a values thing. I’m here to protect children, and I won’t let bad things happen to children if I can at all help it. Where it gets more complex is in the classroom when behavior is happening, and the risks aren’t so obvious maybe, that’s where we need to work a little bit more on the decisions and how they’re made and make sure that they’re coherent and congruent with the legal framework.

Al: Let’s go back to the harm staff one, which you said was the biggest issue in the primary schools, and just talk a bit about it.

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, and I wanted to come back to that. Yeah, for sure, because one of the most transformative moments in my career so far was I was standing in a classroom teaching this positive handling material that we teach, and at the break, about 10:30 in the morning of the first break, I’m making a cup of coffee, and a woman sort of sidles up next to me and she says, “I’m really glad that you’re emphasizing the safety of staff, because I don’t take my safety for granted anymore in the classroom.” I turned to her as I was stirring my coffee, I said, “Oh, tell me why.” She said, “Well, I’m just coming back into work, I’ve been away for two-and-a-half years because a young man I was looking after put me in a coma when I was in the classroom working with him.

Al: Oh wow.

Gerard O’Dea: I stopped stirring my coffee, I looked at her, I said, “What happened?” She was happy to tell me the story. I won’t go into the story just now, because I think it’s quite identifiable and I wouldn’t want to put somebody under pressure like that, but what we are very sure of doing is saying to people, and I’ve been in various scenarios over the years, in various schools where I’ve visited and worked with teams, where we’ve heard of the real extreme results that can happen even with primary-aged children. We always ask the question, we say at some point on a training course, “Can everybody agree with me, that a primary-age child has the capacity to put you in the hospital or give you a life-changing injury?” The staff teams who’ve been there, who’ve seen it, who’ve been on the receiving end of a very distressed child, whose gone to that place where they’re being violent, they all nod, and they agree with that statement.

Gerard O’Dea: I think that’s a shocking thing for most people to acknowledge if they’ve never seen it, is that a primary-age child, and I’m talking about five, six, and seven year-olds, can actually produce situations where the adult that they’re dealing with has to go to hospital to have something fixed or worse. I think that’s a really key and unusual thing for people to understand about what can happen in the classroom.

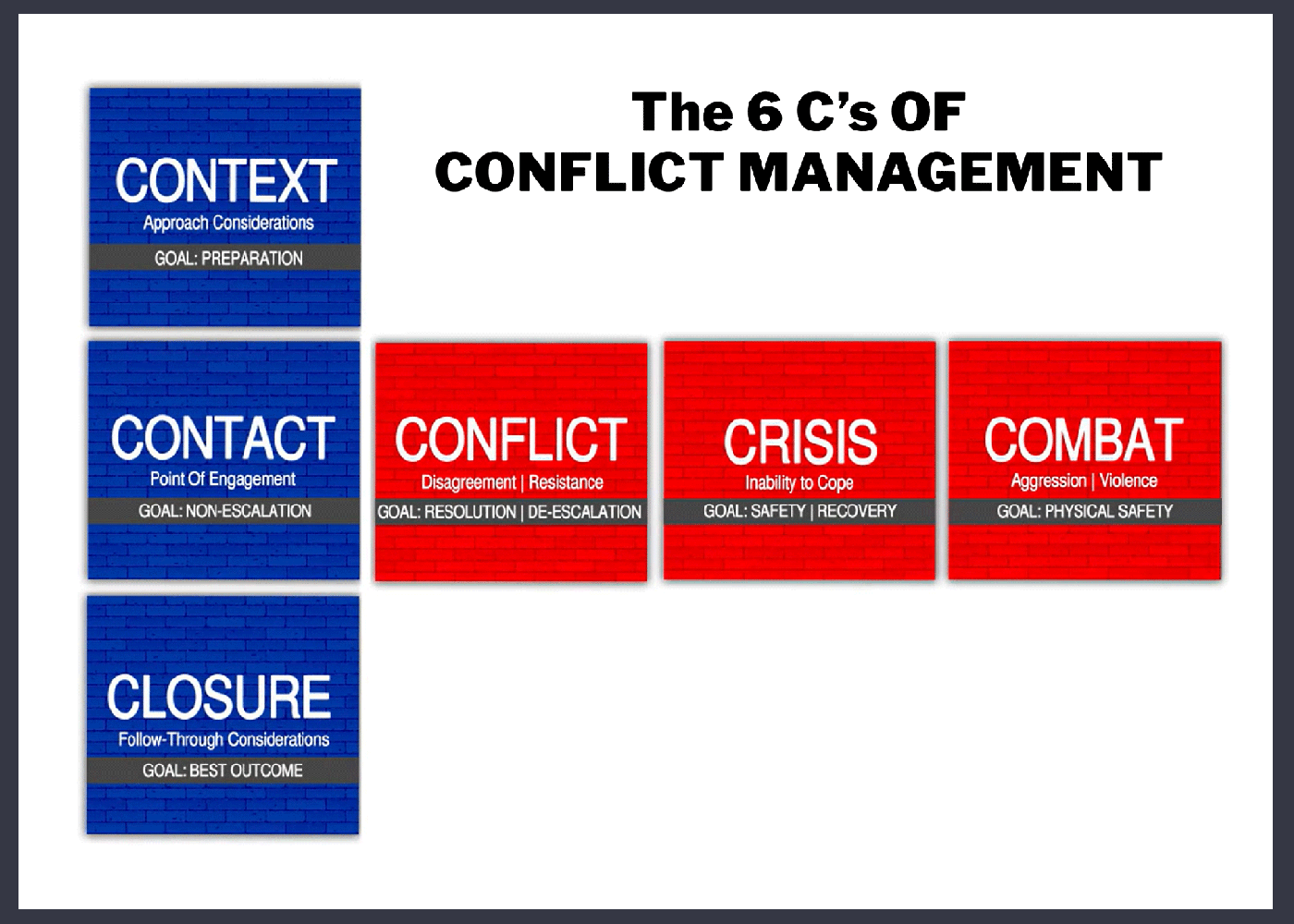

Al: We have this … our framework, we call it the six Cs of conflict management, but we talk about the blue-brick road, which is context, which is understanding everything before you approach somebody, contact, which is when you actually are interacting with them, and then closure being how do you end the interaction. But on the what we call the red-brick road, is when things escalate, and we have conflict and crises, and then combat is the third one, and you’re describing combat, where somebody’s actually getting hurt. When we’re dealing with administrators, sometimes we have people that they don’t want to admit that that combat can happen. But like you describe, you talk to the frontline staff, and they either have a personal experience where it did happen, of they’ve certainly maybe heard of somebody where it’s happened and they readily admit that, “Yeah, that’s a reality and we got to be ready for it.”

road, which is context, which is understanding everything before you approach somebody, contact, which is when you actually are interacting with them, and then closure being how do you end the interaction. But on the what we call the red-brick road, is when things escalate, and we have conflict and crises, and then combat is the third one, and you’re describing combat, where somebody’s actually getting hurt. When we’re dealing with administrators, sometimes we have people that they don’t want to admit that that combat can happen. But like you describe, you talk to the frontline staff, and they either have a personal experience where it did happen, of they’ve certainly maybe heard of somebody where it’s happened and they readily admit that, “Yeah, that’s a reality and we got to be ready for it.”

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, and I think it can be shocking for people who aren’t involved in it to know that is the level of violence, that’s the kind of thing that can happen when really distressed children need to express their distress and their frustration and their panic sometimes through violence and they direct that towards other people. For me, in my career, it’s been just a strange place to end up. Like I always thought we would be teaching people to use force on adults, so hospital security is a great example of that. But, in my career, certainly the vast majority of the situations we’ve been asked to help in have been to help adults deal with the violence of children.

.png?width=2000&height=2000&name=Vistelar-Blog-Call-Out-Campus-Life%20(2).png) Al: Interesting. It’s too bad, it’s the reality. We talk about when/then thinking. Thinking when is this going to happen so you’re ready for it, versus if/then thinking, of going, “Well, maybe it’ll never happen, so let’s not worry about it a whole bunch.”

Al: Interesting. It’s too bad, it’s the reality. We talk about when/then thinking. Thinking when is this going to happen so you’re ready for it, versus if/then thinking, of going, “Well, maybe it’ll never happen, so let’s not worry about it a whole bunch.”

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, very much so.

Al: Describe a little bit then, what do you … let’s use that example, so what do you … you have a staff of elementary school teachers, or maybe the response teams, or the special needs teachers or whatever, and you go in and you’re going to help them with that issue, just give a little summary on … for our listeners as to …

Gerard O’Dea: As we begin a training session with these groups, we’ll gather sort of a training these analysis from the management, before we ever arrive at the school of course. But then it’s really important to touch base with the staff. As I think Alex touched on … Alex Hunter who you did a podcast with recently, he touched on, is that we need to really get the staff to trust that we know where they’re coming from and that we empathize with their position. So we do work with the staff in the initial part of the day to kind of get their feelings on what situations are bothering them and concerning them most. We talk about that very much, and we get some examples, and we try as much as we can in the time we have to understand very much the specific scenarios they’re getting into with the specific children that they’re having issues with so that we can try to help with specific strategies.

Gerard O’Dea: Then we set up scenarios and we try and replicate some of the behaviors and some of the things that the children do. We will take the staff through a series of tactical tips that should help them to stay safe and keep the child safe throughout. Those tactical tips will include from our Vistelar methodology, some non-escalation tips, some de-escalation tips, but very quickly our staff who we train on these positive handling courses, really want to know the physical ways they can keep safe. Because they’re already trying everything they know to de-escalate situation, and to not to have them happen. They really want us to get to the physical.

Four Types of Force to use when things get Physical

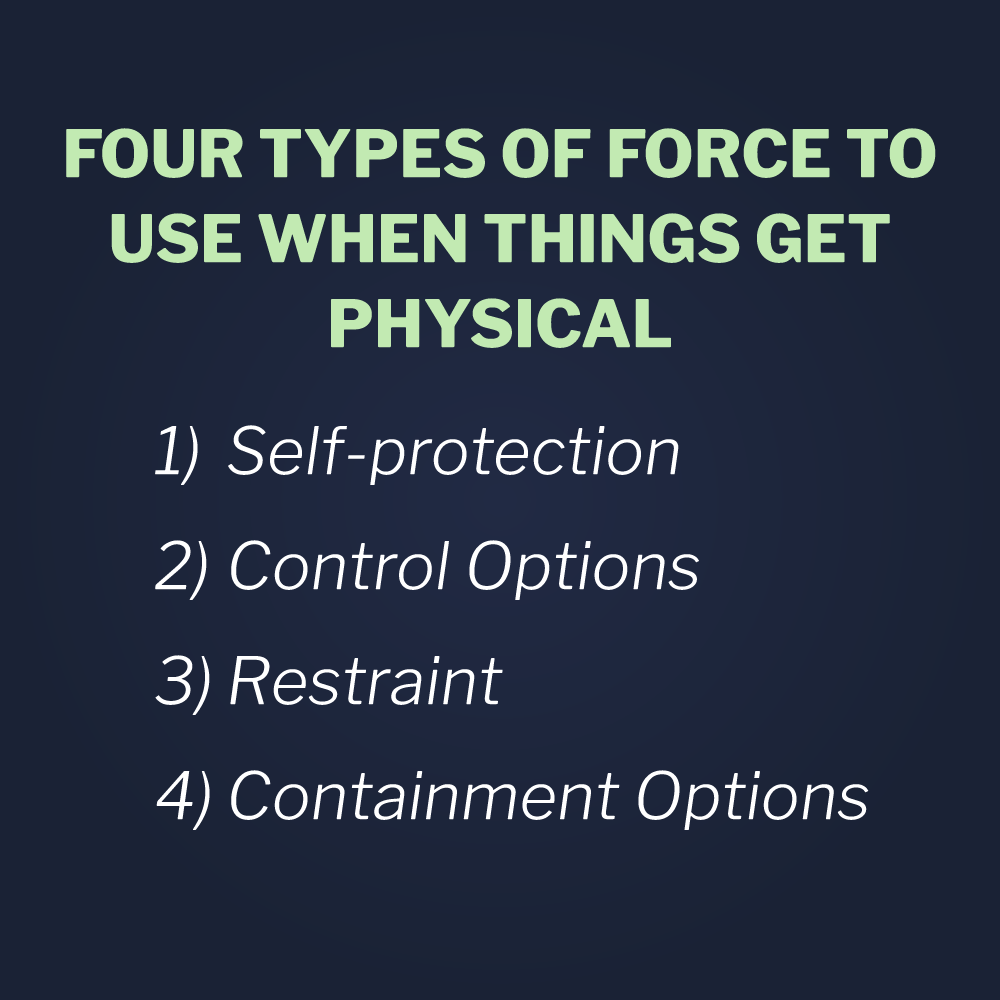

Gerard O’Dea: Within the physical, we teach four options, or four types of force that the staff will probably have to become familiar with. Those four are; self-protection, control options, what we call restraint, and then lastly, containment options. Those are variations on a theme, which is called use-of-force. Self-protection’s quite obvious. That’s if something’s happening to you, and you have a child trying to hurt you, what are the things you can do to keep yourself safe? Control and restraint come together as a pair, because they are early and late phases of the same activity.

containment options. Those are variations on a theme, which is called use-of-force. Self-protection’s quite obvious. That’s if something’s happening to you, and you have a child trying to hurt you, what are the things you can do to keep yourself safe? Control and restraint come together as a pair, because they are early and late phases of the same activity.

Gerard O’Dea: Let’s say you have a child who is maybe trying to hurt another child, well you have to probably, if you make the decision to do so, you go over there, and you put your hands on the child, and the child will still be moving, and those initial attempts you have to make the child safe to maybe move them away from the other person that they’re trying to hurt. That would all be described in our methodology as the control phase, IE, it’s quite frenetic, there’s quite a lot of chaos, there’s movement, and so on.

Gerard O’Dea: Once the staff has moved through that, and they have a more secure stable element of control happening, we then call that the restraint phase, or the immobilization phase where the child isn’t able to move as much and certainly isn’t able to hurt anybody. That’s kind of a continuum, self-protection, control, restraint, those phases. Throughout all of that, the teacher has, or the team I should say, the teacher, the teaching assistant, the people involved, always have, or should be considering the option of containment.

Gerard O’Dea: Containment is where because of what’s happening and the level of violence that the child might be presenting, the question becomes, can we all withdraw and pull the other children away from this person and keep them in an area where they can’t hurt other people at this moment? That is what we call containment. It generally might involve shutting a classroom door, and letting the child feel like … work out their frustration and violence, but with anybody near [crosstalk 00:37:32]

Al: So you get everybody out of the room.

Gerard O’Dea: Now I just want to make a distinction in that … Yeah, and it’s an emergency intervention that you do in the moment. It’s very differentiated from a practice called seclusion, which we don’t really as a training provider, we don’t really

think you should be secluding primary aged children, and that you’ve no business really secluding a secondary-aged child unless there are very specific circumstances that have been very clearly documented and so on. I which want to differentiate that, containments this emergency [crosstalk 00:38:07]

Al: Make sure the listeners understand the distinction between containment, or I think our term would be separate and support, and then seclusion. What’s the difference?

Gerard O’Dea: Yes. I’m not really a specialist on seclusion, but because we’ve never advocated it in schools for sure. It’s a very controversial issue here in the UK right now. I think if you’re watching the news generally across the world, there was a big expose on some stuff they were doing in Illinois recently, where if a child misbehaved in a classroom, then somebody would lead the child out of the classroom into a corridor down to a special room that was maybe six feet by six feet, maybe padded on the walls, put the child in the room, shut the door and seclude them from their peers, and seclude them from the rest of the school, with the door shut until [inaudible 00:39:08] they decided to behave.

Gerard O’Dea: That idea of leading a child to a place where you put them in a room or a box and then shut the door on them is something that probably in all likelihood is very

traumatic for the child, especially if they have a history of previous trauma or adverse childhood experiences. That’s different to some emergency happening, a child smashing a chair on the ground or pushing furniture over in a room, and we just ask everybody to get out and remove themselves from that area and then we have a cordoned, if you like, the child is in one place being very violent, and everybody the child could hurt is another place.

Al: Yep, makes perfect sense.

Gerard O’Dea: We’ve asked everybody to leave, that would be my decision.

Al: Let’s go back to control, so I think self-protection, I think people have a basic understanding what that means, you’re protecting yourself from getting hurt, and protecting your head, whatever, you showed us some of that when we were over there, and then restraint is more of a … like an escort hold or something to say, “Okay, let’s …” basically you’re keeping the child from hurting others, in a simple … we use the word escort-hold, I don’t know what you call those, what name do you put on those? Control-hold?

Gerard O’Dea: We refer to them as holds. We just have names for them-

Al: The specific hold.

Gerard O’Dea: … which describe the parts of the person we’re holding, maybe like a wrist hold, or a-

Al: Yep, okay.

Gerard O’Dea: … something like that. We don’t use words that describe the purpose necessarily, if you understand what I mean.

Al: Yep. I think people can imagine what that, but what would a control-thing look like? Give me [inaudible 00:41:13]

Gerard O’Dea: For me coming into this 14 years ago and looking at tactics, it was … and then working very much on realistic … a study of the realistic things that happen when bodies collide, I was always interested in the fact that when people were taught how to hold somebody, the person was generally … when you looked at the practice in the training rooms, the person was often just standing there and then a team staff walked up to them and they helpfully put their arms in a certain position.

Al: Exactly.

Gerard O’Dea: The staff standing to the side of them put them in a hold. I was always interested in that that does not replicate in any way how you would have to enter that person’s space, and then secure their arm in an effort to put them in that hold.

Al: Exactly.

Gerard O’Dea: I would describe the control phase as all the bits and things that you do between let’s say to use Vistelar 10-5-2 framework, between being at 10 feet and then being at 2 feet, zero feet, all of the work you’re doing before the hold is secure, that’s the control phase.

Al: Okay got it.

Gerard O’Dea: We have various of way of exploring that with staff. I think our experience is that in contrast to some of the other types of training, methodologies and providers, we found that the staff who see our methodology in terms of control tactics really helpful, because it fills in that blank for them, which they’ve always had this kind of … what’s that word for when you’re trying to hold to their front [crosstalk 00:42:53]

Al: Cognitive dissonance, yeah.

Gerard O’Dea: Thank you Al, I had blank on that just now. But staff always have that cognitive dissonance where they go, “That’s hold, and I’ve practiced the hold just now, but I’m not sure, there’s a blank in my brain somewhere as to how I get there safely.”

Al: Exactly.

Gerard O’Dea: We’ve always tried to help staff with that.

Al: Give an example of just one thing, just so the listeners can have a sense for what that looks like. What would be a control method that would fill in that gap?

Gerard O’Dea: We have a block of training that we refer to as in various ways, but it really has to do with, what are the optimal grip points, or the optimal contact points between me and the other person when they’re moving really rapidly? So there are various places on the body where I might put my hands that suppress their movements and keep me safer.

Al: Got it.

How not to hold someone

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, so we have various things like that. In that block, we explore with the staff where are better places to hold onto somebody and less optimal places to hold somebody. I’ll give you an example of a negative if you don’t mind, the negative is one of the … historically one of the things that the martial arts teaches is releases from wrist grabs, and that’s always fascinated me because … and I’ve practiced Aikido for a long time, and I’ve studied classical and traditional martial for a long time, and they spend a lot of time on releasing wrist grabs, but the truth of the matter is when everything’s going very kinetic, and people are moving very fast, if you grab somebody who’s moving very fast and violently by their wrist, that grip is not ever going to be very secure, just because of the angles that are created and so on.

Gerard O’Dea: If we said to staff, “Go in there and grab hold of that person’s wrist,” it’s extremely difficult thing to achieve, and then it’s easy for the person to get out of. That would be not an optimal point of contact between us when things are moving very violently and I’m trying to control the other person. We have other ideas for staff, and we soon dispel some of the things that they may have been trained to do which is to grab a wrist, and instead to focus on other parts of the person’s body.

Al: Yeah, love it.

Gerard O’Dea: That has been really helpful for them. Just think about it, the fastest moving part of the arm-system, when you’re looking at somebody who’s flailing around, the fastest moving part of that system is the person’s hand and wrist.

Al: Right. Right.

Gerard O’Dea: And so we have to ask what’s the slowest moving part of that system, and that’s probably where we should try and put our hands.

Al: Love it.

Gerard O’Dea: Yep.

Al: I mean this makes so much sense, right? Again, I think that the average teacher or first-responder would understand self-protection, they’d understand restraint, they’d understand containment, but I think this gap thing is an incredibly important point, that there’s gap between showing up and getting them into a restraint situation that nobody knows-

Gerard O’Dea: A hold.

Al: It’s like, “What do I do? How do I do that without getting hurt?” Right? Yep.

Gerard O’Dea: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Yeah, it’s just that mental, what do we call it? Like a psychological void, and that cognitive dissonance I think is a really interesting thing to explore because when we show it to people, they really start to nod, they go, “This is going to help me. This is going to help me.” I know how to do holds. A lot of the people we train, they’ve had training from other providers. Because in the UK, this positive handling training is very deeply embedded in the school cultures, so people get training almost every year in schools where they have a wide population of pupils, and they have different behaviors.

Gerard O’Dea: It’s very common that people will come to us and they’ll have had training before, but this really is a different thing, different approach that we’ve taken. You can see some light bulbs going off in the training room when we cover that material.

Should all staff members receive this training?

Al: When you say that it’s embedded in their culture, is it the entire staff, or a subset of the staff that’s getting this every year?

Gerard O’Dea: That’s a great question. We have in the long and distant and dark past been asked by schools to teach the whole school. If you can imagine trying to corral, and we did try this, I’ll admit, put my hands up, years ago we were asked to train a staff team of about 60 at a school. For safety-ratio purposes, we had to gather a huge team of trainers to do this, because the school wanted to put them all in a big gym and train them all at once in the one day. Yeah, if you can imagine, and I have to say, this was a awful long time ago, and we were still figuring some stuff out as a business. But all the teachers came back from summer holidays, on their first day back, they ushered them all into a hall and they put them in front of me and my trainers. It was trying to corral a convention of … I can’t even … You can imagine though, right?

Al: Oh yeah. Yep.

Gerard O’Dea: I then very quickly came up with a decision that said, “Look, schools probably shouldn’t train all their staff.” If you think about a distribution curve, on the left-hand side of a distribution curve in a school, you have people who really don’t want to, and aren’t psychologically ready, and maybe even disagree with the restraint of a child, so those are people you probably shouldn’t train and shouldn’t be putting into situations where they might have to do that.

Al: Right.

Gerard O’Dea: At the upper-end of the scale, the upper-end of the distribution curve, you probably have people at your school who aren’t that great at behavior, they’re not great at controlling their own behavior. They maybe have a short fuse, and so they’re more likely to be in trouble in terms of making good decisions if they’re faced with that kind of situation. You don’t want to put those people in those scenarios either. Then, what you’ve got left is everybody else in the middle and I think the analysis there for a teacher, or school, sorry, a head teacher, is to say, “Who are my people who are most often dealing with these kinds of behaviors that then require this kind of decision-making?” Those are the people that we need to train.

Gerard O’Dea: In a school staff of about 50 or 60, you probably finding 12 people who need the training. That’s often the size of group that we’re dealing with give or take. It includes all those people I mentioned before, the inclusion manager, the special educational needs coordinator, the deputy head teacher in terms of pastoral care, and so on and so forth, maybe the teaching assistants who are specifically designated to those children who have the additional needs. By the time you’ve made that list, you’re already heading towards probably the right number of people.

Gerard O’Dea: The good thing about that I think is that those people, because they’re with the children who display those behaviors more often, they know the children really well, and they’re also getting more experience in how to do de-escalations.

Al: Right. Exactly.

Gerard O’Dea: How to prevent and how to behave during an incident. The more experience those people develop, the better they get at it and the better outcomes I think we’ll get. Whereas training everybody and saying that everybody at the school is responsible for this, you’re distributing the experience across the whole school team and you’re making everybody responsible and I think you’re going to get poorer results, poorer outcomes.

Al: Love it. You do the math on what you just described it sounds like that’s what? 15 to 20% generally, is that what you think in terms of? You said 10 or 12 [inaudible 00:51:29]

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, that sounds about right.

Al: Yeah, the school district we were at-

Gerard O’Dea: Sounds about right.

Al: … earlier this week was … they were basically right in the middle of thinking this through right now. We’ve already gone in and done our non-escalation, de-escalation, the non-touching training for the staff. I think that makes all kinds of sense of making sure that people know how to prevent conflict and then prevent it from getting to a physical engagement. But then, on the physical side, they’re thinking about 15% that would ultimately get trained on the physical skills.

Gerard O’Dea: I think that’s about that right. We refer to that team as the behavior team at the school.

Al: Okay.

Gerard O’Dea: When a teacher comes across a situation and it seems to be escalating, they have a means of calling assistance. When they call for assistance, that team responds, or members of that team respond. That seems to be working out really well.

Al: The term that I’ve heard here is response team, same idea, but exactly. They did mention … I’m curious what you do here, they said, “Obviously if you’re going to do this, you need a good communication system,” and that not everybody has their … has a radio and whatever, but what happens in the UK in terms of notifying the behavior team, do you know? Is it just cell phones and stuff or …

Gerard O’Dea: We have a really neat analog way of helping some schools.

Al: Just yelling.

Gerard O’Dea: And then we have right up to giving advice that … Well I’ll explain that to you in a second, we call it the card system.

Al: Oh, okay.

Gerard O’Dea: Then with some teams I say to them, “Look, I really think you guys should be using radios, really need to consider going down to the hardware store, or wherever you get them from and buying a set of four or six really, really good quality radios, because of the levels of behavior you’re seeing and the risks that you’re facing.” These are the people who probably need them. That again would be born out by risk assessment. But what we generally recommend to schools is absolutely that, they need a means of calling for assistance. For years in the UK, there’s been this idea abroad that you could use this red card system.

Gerard O’Dea: How that works is, you have a red laminated piece of card, and it might have the room number that you’re in on it, and it’s stuck with a piece of blue tack next to the light switch in your classroom. At the beginning of the year you would brief your kids, your children in your classroom and say, “If I fall over and I don’t look like I’m very well, or if Jimmy over there has an asthma attack and he needs help, or if Jemima over here, who has really bad allergies and might need an EpiPen, or if there’s some behavior issue, I might say to you to please take the red card. And what that means is I want you to take the red card off the wall where the light switch is, and I want you to go to where you’ll find some adults and I want to hand the card over to them.”

Al: Oh, love it. Yep.

Gerard O’Dea: They hand the card over, and the card says, “Mrs. Jones in Sycamore room.” That person who received the card knows that there’s an emergency of some kind in Sycamore room. That can trigger all kinds of things. In a way, it relies on the most reliable child in your classroom, the very responsible children that are in every classroom. We rely on them to do this particular task when we’ve decided that there’s an emergency in the room. That’s called a red-card system. It’s very analog. A lot of schools use it to my knowledge, and they use it quite effectually.

Al: The idea is … so the card gets in the hand of a responsible adult, and then that adult either … they would know then who to recruit then to get to respond, yep.

Gerard O’Dea: Yep. The alarm’s been raised, and now we test the response. Of course, we’ve always said to the schools that if they do use a red-card system, they should test it for … whether it’s fit for use.

Al: Exactly.

Gerard O’Dea: I have to tell you, I think you’ll enjoy this, is that I was at one school recently and they had kind of corrupted the red-card system because if a teacher needed to go to the loo, or if a teacher was having … she had a headache and she wanted somebody to bring her some paracetamol or something, that she would send the emergency card. Eventually it broke down to the point where, whereas in the beginning they would have a 90-second response time, it got to the point where the response time was like 20 minutes, because it was, call it being corrupted. It was being used for the wrong reasons. [crosstalk 00:56:17] we have a 10,000-year-old fable about a crying wolf to teach us not to abuse these alarm systems, right? But I just found it really funny. It’s just human nature-

Al: Gerard, you just … you brought up a … I was over at our local YMCA, I don’t know, do you have YMCAs in the UK?

Gerard O’Dea: We do, yes, yep.

Al: One here locally, so I’m actually in the hot-tub and we’re talking about whatever, and somebody, I don’t know why the question came up, but somebody said, “If you thought about English, and you said, ‘Okay, we have the US English and the UK English, is that a different language, or just a different accent?'” We didn’t have a good answer. People say, “Well I think it’s just an accent, it’s the same language,” but then I said, “Well, I just was over there, and there’s certainly … they use words that we don’t use here, so it’s also a different language like loo, you just made … had two loo-

Gerard O’Dea: Like loo, yeah.

Al: … what was the drug? Paracetamol, is that what it is?

Gerard O’Dea: Yes. I’m not sure what you guys call that.

Al: I think that’s our acetaminophen actually, yeah. Pretty sure it’s the same.

Gerard O’Dea: Oh wow, okay, I never heard of that, but-

Al: Paracetamol, never heard the word. Way back in my past, past history, long time ago I was a pharmacist, so I’d know that word from then, but, yeah, nobody in the US would know paracetamol is, yeah.

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, we could get into that, it’s probably not relevant to this discussion, but yeah. I know it’s interesting for people when they go to the US and they need to find a pain killer, everything’s got a different name for it over there.

Conclusion

Al: Exactly. Gerard, I mean, we’re coming up on an hour, so this is great. I think there’s certainly an opportunity to talk again, probably multiple times. As you know we had a podcast with one of your trainers, Alex Hunter, which was just brilliant, and we’re going to have multiple more with him. We might ask you to join one of those, because that was just fascinating, this whole empathy thing and his experience with empaths, and his resilience training. I’m just over [inaudible 00:58:36]

Gerard O’Dea: I’d have to say I really enjoyed the podcast. Even though we’ve been working with Alex and having him visit our customers for years now here in the UK, we

don’t get enough time as a team to sit down and dig into everybody’s individual experiences, and Alex certainly has a lot to offer. We’ve got, I think, one of my jobs over the next year, and with your encouragement I think, is to try and demonstrate the teams’ expertise a little bit more, because we’ve got really good trainers. It’s a small team of really good trainers. I want to make sure that we’re supporting them and making sure that the world knows what it is they’re particularly that they’re good at and just how deeply they study their topic.

Gerard O’Dea: When I was listening to your interview with Alex the other day, I was just blown away by the depth of interest and the committeemen that he brings to his craft, and that’s something we all enjoy.

Al: The depth of his expertise, yeah … again, everybody knows Gary and I were over there for nine days. We had an opportunity interact with your, what you have, five or six trainers in the room I think?

Gerard O’Dea: I think, yep.

Al: Plus some of these customer, like Circo was there that you mentioned at the beginning of the call. [crosstalk 00:59:51] over the top impressed of the range of

backgrounds and the commitment. I was just like, “Wow.” I mean, this is a very cool group. Some of the relationships that they have with you go back years, right?

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, for sure. Yeah. We’re very lucky. We’ve kept the team small over the years because it’s just so important to me that when we go and we stand in front of a customer that we’re not just reading from a manual, but that we have answers for people that are really well considered, and that we have depth and substance when we give advice. We’re delighted that all of the trainers who work with us have that. I think what’ll be interesting for you as we go on, and [inaudible 01:00:42] develops more is just to find those areas where that training team we have assembled has really specific specialties in different areas and interests in different areas.

Gerard O’Dea: Just as it’s been interesting for us to explore Joel Ashley’s extraordinary experience in hospital security and so on, and Gary’s experience. For me, when I speak with Gary about defensive tactics and tactical training, I’m always learning new things, because his depth of knowledge is just so deep. I really want to encourage my team to just keep going, just keep digging deeper and deeper into their subject matter.

Al: Love it. Okay, well we’re going to talk again Gerard. I think what you’re suggesting, which I’m 100% supportive of, is that we do this other members of your team beyond Alex. I think we’d learn a lot. Thanks so much.

Gerard O’Dea: Always a pleasure.

Al: We’ll talk [inaudible 01:01:43]

Gerard O’Dea: Great stuff. Great [crosstalk 01:01:44]

Al: Enjoy the new house and the new lake.

Gerard O’Dea: Thank you very much.

Al: Is it Lake Country or Lake District?

Gerard O’Dea: We call it the Lake District.

Al: The Lake District, I love it.

Gerard O’Dea: Yeah, the Lake District.

Al: Okay. Take care. Well that wraps up another episode of Confidence in Conflict. Hope you enjoyed this followup discussion with Gerard O’Dea of Dynamis. As always, if you want more expert advice in how to prevent and better manage conflict, subscribe to this podcast at Apple Podcast, Stitcher, or wherever you get your podcasts. If you like this episode, please write us a review. Also, visit vistelar.com/blog to get notes for this show, share your comments, and access additional conflict management resources. Take care and stay safe.

.png)

.png)

.png)