Enjoy this excerpt from one of our published books.

Chapter 5

Communication Tactics for Campus Life

Amanda walked into the party, still shook up from the walk over. She couldn’t believe what had happened, and was scared to think about what would have happened if she hadn’t run into Jordan. The party was packed. The music was so loud that the bass was vibrating the pictures on the wall, and it even knocked a few onto the floor that was covered with beer and red solo cups. Everyone was shouting and laughing and doing something different. Some were dancing, some were playing a drinking game she had never seen before, and several people were out front lighting off fireworks. “Ouch,” she said, as she got run into by two guys who were play fighting. “Whoa, my bad ‘bout that girly. Haven’t seen you before…freshman?” Said one of the guys. “Hi, I’m Paul, and that’s Brian. Have a drink!” Paul handed her a red solo cup filled to the brim that smelled awful- it was some concoction of booze and juice, one that Amanda had no intention of drinking. “Nah guys, thanks… but I don’t drink. You drink it.” And almost as fast as she said it, it seemed the music stopped and everyone stopped and stared at her in disbelief. “She doesn’t… drink?” Said one. “Ha, well she does now!” Said another, as she pointed towards several people trying to grab her. “To the keg then! Congrats freshman, you’re about to complete your first keg stand!” Amanda was terrified, and suddenly found herself being drug into the kitchen by several people she didn’t know.

So far, this entire book has been dedicated to personal safety awareness, and what you can do to evaluate your environment and stay safer in it. Now that you know how to manage your space and how to identify and avoid threats, we are going to completely shift gears and look at several communication strategies. These communication strategies are meant to be used in tandem with all of the physical skills you just learned about. As mentioned before, you must mesh the verbal and non-verbal skills together in order to avoid conflict and defuse it. Unfortunately, conflict may come to you when you least expect it, just as it did for Amanda. I couldn’t write a book about campus safety without including the communication skills necessary to try and prevent situations from becoming physical. In fact, if you look at law enforcement statistics, you will find that the majority of all law enforcement encounters end without having to use force. If cops, firefighters, teachers, and nurses can use these communication skills to manage conflict and maintain their safety during extremely stressful circumstances, so can you.

It All Starts With Respect

At Vistelar, we believe that one of the best ways to manage conflict between people is to identify and recognize the things that all people have in common. In the middle of a conflict, it is important to recognize how you’d like the conflict to end, and if you see someone else getting into an argument or in an uncomfortable position, you should try and put yourself into their shoes, and see the situation through their eyes. This demonstrates empathy, and it is a highly useful tool in figuring out the most respectful way to resolve a situation. In the previous scenario, Amanda just found herself in a horribly awkward position, and she may not be able to get out of it unless she can convince the partygoers to change their behavior. Unless one (or more) of her friends decides to step up and intervene, Amanda will have to talk her way out of it.

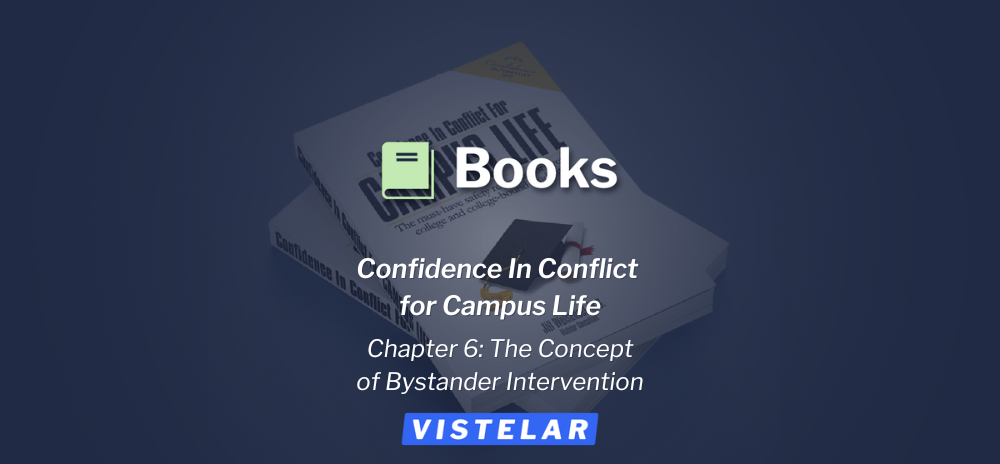

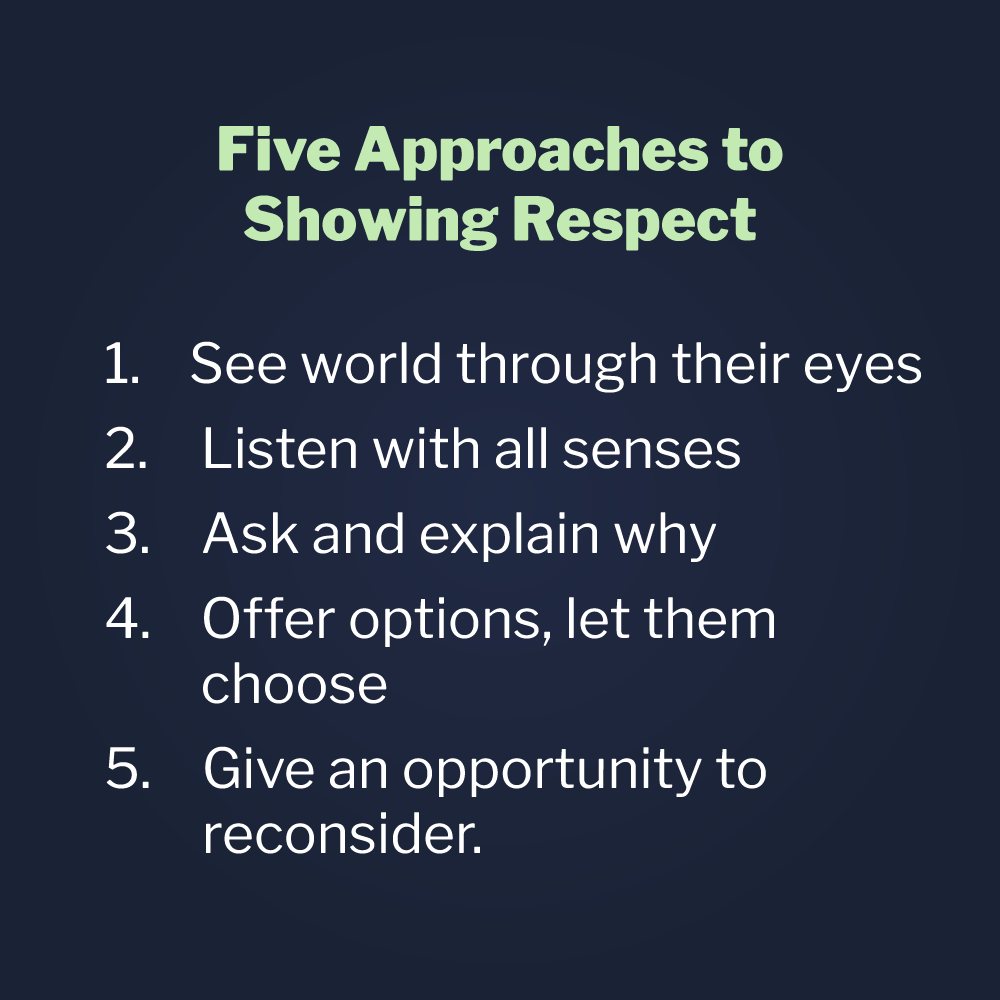

Vistelar teaches this core principle of conflict management: treat people with dignity by showing respect. Over the last thirty-plus years of working with almost every profession, Vistelar has learned that treating people with dignity just works better in managing conflict and had identified these five approaches to showing respect.

- See the world through their eyes

- “Listen” with all of your senses

- Ask and explain why

- Offer options, let them choose

- Give opportunity to reconsider

These five approaches describe how all people want to be treated. Everyone wants to be shown empathy, listened to, asked to do something rather than told to do it, be provided with an explanation for why they are being asked, offered options from which they can choose, and given an opportunity to rethink a decision. It is important to understand that Vistelar does not teach that you need to respect everyone. That would be impossible, since respect is based on your personal values and must be earned. However, it is essential – if you want to be effective at conflict management – that you show everyone respect. All people deserve to be shown respect.

To see the world through the other persons’ eyes and to listen with all of your senses, is the starting point for any successful interaction. If you aren’t paying attention to what a person says, observing what they do, and noticing how they respond, you won’t be able to persuade them to cooperate or collaborate with you. Vistelar emphasizes listening with all of your senses because there’s a lot more to notice than just what someone says. We’ll get into this skill more when we talk about Beyond Active Listening later in the chapter.

Let’s use our example above, and pretend that an onlooker at the party was paying attention enough to notice that Amanda was terrified of having to do a keg stand. That onlooker would have been listening with all the senses—not just hearing what was happening, but seeing the fear on Amanda’s face, feeling her worry about how to handle the peer pressure, and empathizing with her desire to get out of that situation.

When just listening isn’t enough to resolve the situation, you need to speak up. Approach three (ask and explain why) works off of the human desire to know “why” we are being asked to do something. Think of a small child who is begging his mommy or daddy for some candy at the store. The parents say, “No, you can’t have any candy right now.” What’s the first thing the toddler says? “Why? Why mommy why?” The usual response you hear from the parent is “because I said so,” which usually results in the toddler asking “why” again, several more times. We know that you are more likely to persuade someone to do something if you ask them to do it, rather than order them to do it, and you may even be able to get them to do it willingly, if you can explain to them why it is important or in their best interest to do so. Lots of times people in authority believe the question “why” is a question against their authority. It isn’t. Being able to give people the answer is actually empowering!

To continue with our onlooker: imagine if this person walked up to the guys “playfully” dragging her and said, “Let her go now! This is stupid.” That sentence is a command, and would most likely generate resistance from the group. However, if the friendly onlooker came up to the group and said, “Hey guys, could you please not force her to do that? I really don’t want her puking on all of our stuff later.” The onlooker is now treating the group with respect. Which approach is more likely to get a positive result?

And if they didn’t let her go and would’ve responded with laughter and told the helpful bystander to get lost? They could then use approaches four and five, and offer the guys options and an opportunity to make things right. They could then say, “Look, I realize you guys are just trying to have a good time, but this clearly isn’t fun for her. What do you say we let her go so we can get back to having a good time? I’d hate to see her get drunk and sick and then tell the campus police tomorrow that people were drinking underage. What do you think?”

The dialogue used by our interventionist is also known as a “Persuasion Sequence.” The Persuasion Sequence works hand in hand with Vistelar’s five approaches to showing people respect, and you are already starting to see how effective it can be. We will learn more about the Persuasion Sequence a little later on.

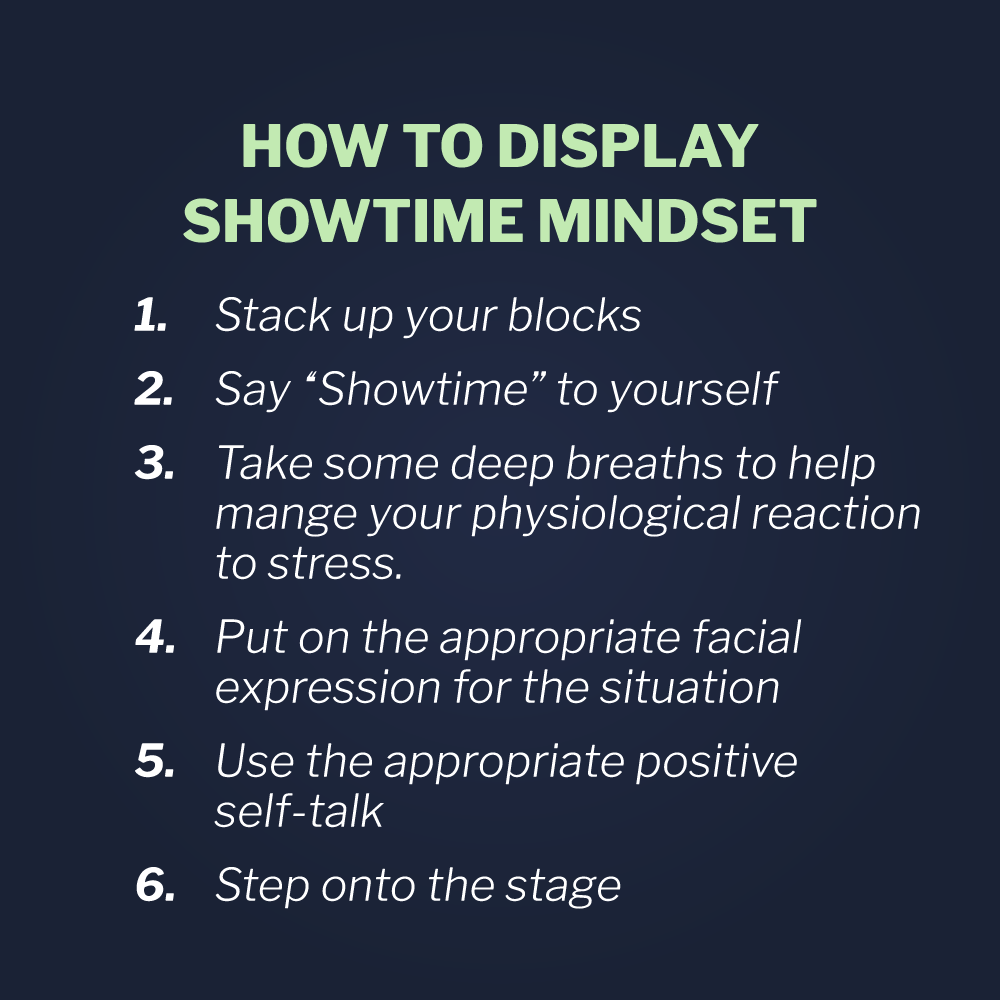

The Showtime Mindset

Another Vistelar concept is adopting a “Showtime Mindset.” Showtime helps us remember that the entire world is a stage, and that people perceive us differently than we perceive ourselves. Think of a time when you spent a lot of time getting ready before going out, and you took one last look in the mirror and thought “Man, I’m looking goooood.” Then right before you walk out the door one of your parents said to you “You’re not leaving the house looking like that… are you?” The idea behind the Showtime Mindset is that the way you present yourself matters for communication, so you should adopt an attitude that projects confidence and self-assurance.

Remember in Chapter Three when I said that it is imperative for your non-verbal behavior to match your verbalizations? What you say has to match how you say it, and what you look like saying it. Research has shown that the majority of what we communicate is delivered through our delivery style. This means that the message we are trying to deliver, at any given time, is delivered mostly through our non-verbal mannerisms, and the pace, pitch, and modulation of our voice. Very little of the message we deliver is in the content of the actual words. So, if you say the exact same thing, but deliver it in a different way, it actually means something different. The skill of Showtime is being conscious of the presence we project through our non-verbals and our tone, so that people will believe the words we use.

verbalizations? What you say has to match how you say it, and what you look like saying it. Research has shown that the majority of what we communicate is delivered through our delivery style. This means that the message we are trying to deliver, at any given time, is delivered mostly through our non-verbal mannerisms, and the pace, pitch, and modulation of our voice. Very little of the message we deliver is in the content of the actual words. So, if you say the exact same thing, but deliver it in a different way, it actually means something different. The skill of Showtime is being conscious of the presence we project through our non-verbals and our tone, so that people will believe the words we use.

Sometimes it is hard not to let our body language give away our true feelings. Have you ever had a really bad day and your mom asks you what’s wrong and knows something’s wrong even though you said you’re fine? A Showtime Mindset helps you guard against that by allowing you to put all of the negative things in your life aside just long enough so you can step up, appear confident, and handle the task at hand.

Think about a basketball player on a free throw line. You can easily tell which players are super confident and look like they will make the shot, versus the ones who appear scared and unsure of themselves. You’ve probably also noticed when a friend has a really bad day at school, and then they play a really bad game. Ever notice how some people can have a really bad day at school and then still somehow man- age to play an awesome game? That’s because they are able to mentally turn off one version of themselves (the student version) and turn on the athlete version. Showtime is a complete mental shift, allowing you to put other things aside, and appear confident, even if you’re not. Sometimes in conflict, you have to fake it until you make it, and put on the face you need to succeed.

To help you understand how you appear to others, I want to introduce the “Less Than, Greater Than, Equal To” drill to help teach the point of appearing passive, assertive, or aggressive. This drill was developed by Vistelar Consultant and martial arts trainer Master Chan Lee to help school kids protect themselves from bullying. In this drill, you think about the first 5-10 seconds that a new person meets you. During that time, they will make a quick determination to assess if they are “greater than you, less than you, or equal to you,” and based upon that designation, they will treat you as such. Now this sounds somewhat superficial, but as a concept, you can see it with how people talk to each other: people who think they are “greater than” someone else, tend to talk down to other people, command them, and use a condescending tone. These people will also “puff up” their postures, increase their gait, hold their head high and start acting like they are better than other people. These types of people become bullies. People who naturally feel “less than,” will tend to “shrink” their posture, avert their eyes, act passively, and speak meekly. These types of people become bullied.

What does “equal to” look like? It looks like confidence without being overbearing. If you show yourself as “equal to”, you will stand up straight; you won’t be hunched over or sticking your chest out. You will look the other person in the eye—not staring them down, but also not avoiding their gaze. When you speak, your voice will be calm and will be at an appropriate volume, neither whispering nor shouting.

The purpose of this exercise is to be specific about what confidence looks like, so you can project it even when you’re not feeling it. The concept shows us that it is possible to “up sell” our posture. Therefore, you can become a less desirable target for bullying, harassment, or victimization. We want you to do everything you can to prevent yourself from becoming a target, while also recognizing that if something bad does happen to you, it isn’t your fault. As mentioned earlier, the only person who can actually prevent the crime from happening is the person committing it.

Emotional Equilibrium

Talking your way out of conflict is a real life skill, and we realize that it isn’t a natural thing to do. At Vistelar we teach many communication concepts that can help make the art of talking out of conflict easier for you. One of the concepts is Emotional Equilibrium. This concept is a complex one, but at its most basic level, it will help you identify and protect against the emotions that make it difficult for you to keep your cool and communicate under pressure during a seriously awkward or confrontational situation.

Think of a time that you were really angry and you got into a fight with your best friend. You notice how hard it was to say exactly what you meant, and exactly what you were upset about? That’s because people rarely say what they mean when they are upset. This means we must try to stay calm so that we can respond to their meaning, rather than react to their exact words. Emotional Equilibrium encourages you to maintain a “still center,” recognizing that in times of conflict you must stay calm, breath, and have your emotions—not “be” them. This means that even when you’re angry or frustrated in an argument you will be able to control your emotions, rather than have your emotions control you, so that you will remain clear headed enough to make good decisions.

In order to maintain your Emotional Equilibrium, you have to take some time to recognize your weaknesses—those things that are likely to set you off and make you really angry. Everybody has “hot buttons” that really makes their blood boil. It is important that you identify what makes you angry and know how you react to them, so that you are prepared to respond appropriately when someone says it to you. For example, one of my hot buttons is having my opinion blown off by someone, who doesn’t know anything about me or my level of experience, just because I’m a female. I have worked very hard my entire career to remain physically and mentally fit by pursuing additional training opportunities, and seeking out advanced education. Essentially, I have worked my whole life to become technically proficient and competent at my job, and that has nothing to do with being female. Because I have worked hard to maintain my skills, I have developed an “Emotion Guard” to keep me from becoming angry when someone disrespects me. My Emotion Guard allows me to project a strong, confident, and unphased image, and it protects me from displaying emotions that I may not want to share with other people.

I have found it extremely useful to adopt the Showtime Mindset in order to maintain Emotional Equilibrium. Conceptually, the two go hand in hand. I know that even if I’m having a bad day at home, I need to put aside all of my problems when I go to work. I’m a supervisor, and if I drag my personal issues into the workplace, it is likely that they will also drag down my crew. Having the Showtime Mindset allows me to go to work and temporarily put all of the negative things in my life on hold, so that I can better perform for my team. By maintaining my Emotional Equilibrium, and remaining cool, calm and collected, my crew is better equipped to do their job, knowing that I’m capable of doing mine even under the most stressful circumstances.

The Universal Greeting

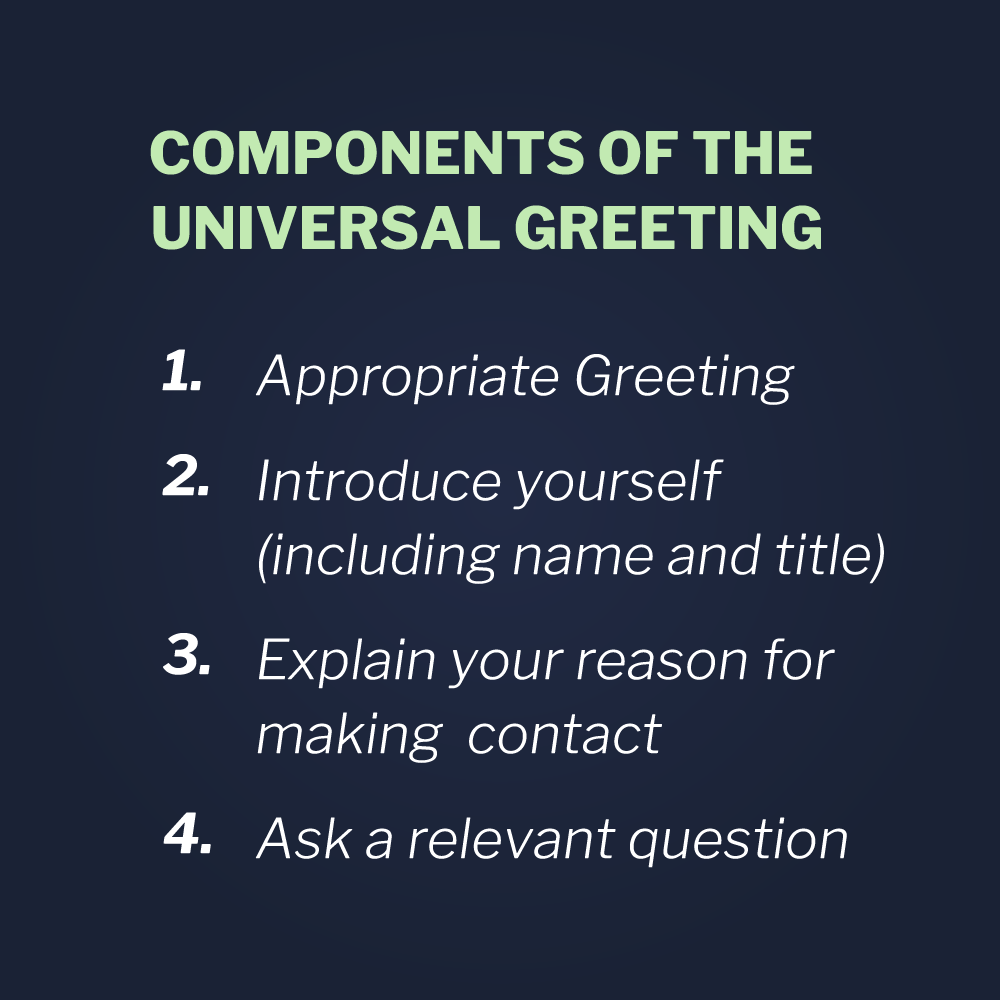

Are you generally shy and nervous to talk to new people? Do you have a friend who just seems like they can talk to anyone, and they make it look easy? There are many skills that you can learn that can help you get through the awkwardness of talking to new people. In light of treating all people with dignity and respect, we teach a communication tactic called the Universal Greeting. The Universal Greeting is a standard, pre-planned way of initiating a conversation with someone that will help you set the stage for a positive interaction. The components of the Universal Greeting are:

- Use an appropriate greeting, such as “Good morning,” or “Excuse me.”

- Introduce yourself and your affiliation, such as “I’m Keith Jones, and I live down the hallway.”

- Explain the reason you’re talking with them, such as “We’re hosting a dorm meet and greet spaghetti dinner as a fundraiser”

- Ask a relevant question, such as “Would you be interested in buying tickets?”

Using the Universal Greeting makes initiating that first, somewhat awkward contact a lot easier, and it sets the stage for a better outcome because you appear confident and courteous. The Universal Greeting allows you to state the reason for why you’re talking with them and makes sure that both individuals engaging in the conversation know what the conversation is actually about. Another benefit of introducing yourself this way, is that it aligns seamlessly with the Persuasion Sequence, in the event that they say “no” to your question or generate some sort of resistance to your inquiry. I will show you how to put both of these skills together in the Bystander Intervention chapter.

Beyond Active Listening

Now that you’ve identified your hot buttons and found a way to stay calm and appear calm under pressure, we are going to talk about going Beyond Active Listening—developing skills that will allow you to truly hear what other people are saying. Other people teach active listening skills, and that’s a good start, but to be effective you have to go beyond just “active listening.” Fully understanding another person’s message requires more than just hearing what someone is saying—you must truly listen to their side of the story and be open and unbiased. Vistelar Consultant Doug Lynch, explains it like this:

“There is a difference between hearing and listening. It is the difference between acknowledging and understanding. Between reacting and responding. Let me share a brief example. Driving back from a presentation in Prescott, Arizona to my home in Phoenix, while coming down a twisting mountain highway, a loud metallic bang emitted from under the rear of my truck. It was time to quickly pull over and examined the vehicle very closely. This stretch of road combining: highway speeds, small guardrails and hundred foot drop offs is not the place you want to lose control of your vehicle. Finding nothing obviously wrong and having no cell phone signal to call for help, I started back down the road but, now, attentive to every sound coming from the truck. In anticipation of a further problem, both hands were placed firmly on the wheel alert to any unusual vibrations in the vehicle, the radio was turned off and I slowed my driv- ing pace to the minimum speed limit. If something started to malfunction, I was in a better place to guide the vehicle safely to the shoulder of the highway. I was now listening to the vehicle until arriving safely at home. Hearing something can force a reaction, listening to something helps you to form a response. In human conflict, this can be the difference between reaching peaceful resolution and not.”

In this scenario, Lynch was hyper-vigilant about what was happening with his car. He was paying attention for anything that might have indicated a problem—an unexpected vibration, an unusual sound, even the smell of something burning or leaking. When we approach a situation with potential conflict, we need to be as tuned in to what the other person is communicating. As I mentioned before, people rarely ever say what they mean when they are upset, so if you were only listening with your ears, you will most undoubtedly fail to hear their message. Beyond Active Listening means also “listening” with your eyes so that you can observe their body language, non-verbal cues, voice tone, and their distance from you. When you are listening to someone, your goal isn’t just to “get the facts.” Your goal is to truly understand the context of their situation. If you find yourself having trouble understanding the meaning of a difficult conversation, use these steps:

- Ask To Clarify: Use skillful questioning to clarify what the person believes, as well as why they hold those beliefs.

- Paraphrase: Put their meaning into your words to ensure understanding. Paraphrasing provides an opportunity to ensure that what you heard is what the other person intended to communicate.

- Reflect: If you need to interrupt, start with “Can I ask a question to see if I understand?” Then state your view of what the other person is feeling and why – and ask if you are correct.

- Mirror: Subtly imitate the other person’s subconscious body orientation, posture, mannerisms, eye contact, tone of voice and talking pace, but never his or her negative body This helps build rapport, trust, and liking so the other person is more open to communicating with you.

- Advocate: Acknowledge the issue and express how you and the other person should work together to address it, for example, say “That sounds like a big problem; let’s work together to figure out how to fix it.”

- Summarize: Use a summarizing statement to make sure everyone agrees with what has been said so you can move forward towards resolution.

The first technique, empathizing, means attempting to understand how the other person is experiencing the situation. Empathy is a challenging skill because you are trying to imagine what is going on inside another person’s head, and often you don’t have the full picture. For instance, you may not know that your roommate just got her first “F” and her fear is affecting your conversation. But, you can recognize that your roommate is more on edge than usual, and you can genuinely try to understand her perspective. When you empathize with your roommate, you acknowledge that something is amiss. As a result, you can ask, “Is there something else bothering you right now?” instead of plowing ahead with your complaints about the dirty dishes in your room.

The second technique, asking questions to clarify, helps establish common ground in the conversation. When done well, asking ques- tions also shows that you are genuinely interested in what the other person is thinking. When combined with empathy, asking questions to clarify helps defuse confrontational situations because the techniques demonstrate an openness to hear what the other person thinks. In order to ask questions well, it is important to choose ques- tions that don’t put the other person on the defensive. The way you ask the question matters. There are five generally understood ways to ask a question:

- Fact-finding: This is good for acquiring specific information or data, and has a neutral effect on the If you ask too many fact finding questions in a row you could appear unempathetic.

- General: This would be an open ended question, such as, “What’s going on here now?” This lets the responder answer the way she or he chooses, and because they can choose their response, it makes them feel good.

Opinion-seeking: Everyone loves to give their Asking a question such as, “What’s the best way to solve this problem?” displays empathy and could give you much more valuable information than just fact finding questions alone. - Direct: These questions require as simple “yes” or “no” They are useful in moderation for focusing the discussion, but like fact finding questions, this could make a person feel interrogated or cornered if done repeatedly.

- Leading: These questions tend to anger respondents, as they feel they are being pressured a certain way and it appears that you already have your mind made up regarding the answer.

A third tool you have available during a confrontational discussion is paraphrasing. Paraphrasing allows you to put another person’s meaning into your own words, and state it back to them to ensure you understood their meaning correctly. If a person is going on and on and you are having a hard time figuring out their point, paraphrase is a good tool because it forces the speaker to pause long enough to make sure you’re understanding them. Generally speaking, this results in the speaker modifying what they originally said, because they will realize they were upset and didn’t say exactly what they meant.

Paraphrase also allows you to “interrupt” someone and not upset them, as if you were trying to cut them off as they were speaking. You can simply say, “Hold on. Let me make sure I understand what you just said.” That will force the speaker to pause and give you a second to process what they were saying so you can make sure you understood it. Doing this also shows the other person that you are in fact listening to them, and that displays empathy!

Finally, summarizing ensures that both parties are on the same page. After you have empathized with the other person, asked questions to clarify their position, and used paraphrase to make sure you understood what they meant to communicate, you still need to move forward—either towards a resolution, or into another tactic like the Persuasion Sequence. A summary is a brief statement of how the situation stands. When you finish summarizing, both parties should understand what each other is thinking.

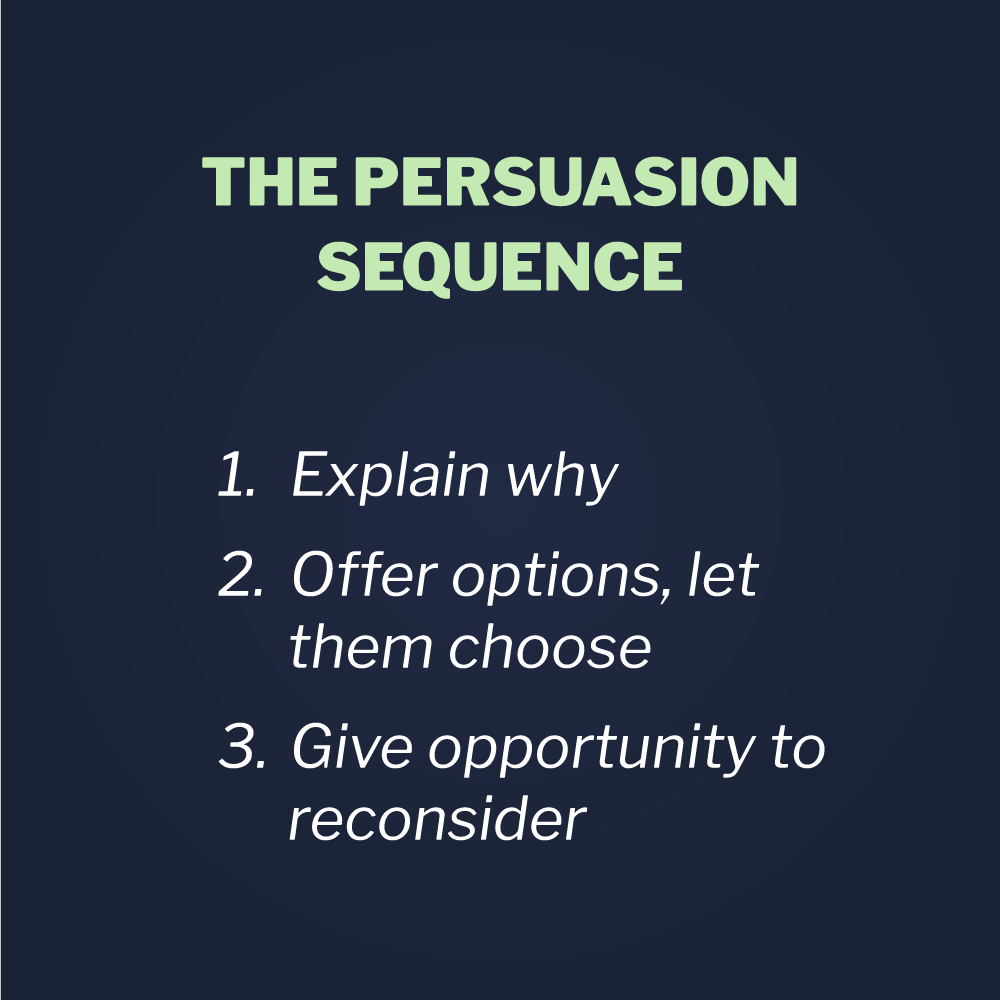

The Persuasion Sequence

The Persuasion Sequence is another pre-planned communication tactic that will help you persuade others and generate cooperation. This communication method is a critical conflict resolution skill. Just as the Universal Greeting ended with “ask a relevant question,” the Persuasion Sequence picks up with what to do if you “ask” someone to do something, and they say “no,” or refuse to respond or change their unacceptable behavior. The need to persuade people usually starts with someone requesting cooperation of another person. Then, if the person questions, resists for refuses the request, the Persuasion Sequence can be used as follows:

as follows:

- Explain why you are asking them to do something and confirm their understanding. You can do this by providing your explanation and telling them why your explanation is Then ask if they understand your explanation.

- If they continue to not cooperate, then you would offer them options and let them choose. Present a vivid description of a positive option and then a negative option. Tell them it is their choice and ask again for their cooperation. Make sure when you do this you use a friendly and cooperative tone so as not to come across threatening.

- Give them the opportunity, one more time, to reconsider their behavior.

If the other person has not cooperated after this third step, your options for Taking Appropriate Action will vary depending on the situation.

Taking Appropriate Action could mean following through on the options you presented, or taking the next best course of action. In a less serious situation, such as an argument with your roommate, the appropriate action might be to decide that it’s not worth pursuing the issue further. In more serious situations, you might call for help or find a way to leave the situation.

Let’s put this into our keg stand scenario from earlier. A bystander stepped up and tried to help Amanda from getting dragged into the kitchen to do a keg stand. The bystander verbally set the context of the situation for the subjects, and then offered options to them, stating, “Look, I realize you guys are just trying to have a good time, but this clearly isn’t fun for her. What do you say we let her go so we can get back to having a good time? I’d hate to see her get drunk and sick and then tell the campus police tomorrow that people were drinking underage. What do you think?” If the guys were to respond with, “Nah, this is more fun anyways,” our interventionist could then say, “Is there anything I can say to you guys so you will leave her alone?” And if not, the interventionist will have exhausted all of their verbal options and will have to follow through with some sort of action (act).

In this case, an appropriate course of action could be to talk to the party host and let them know that they are forcing underage students to drink. It could also be enlisting a couple more friends to help get her out of there (literally “tag teaming” to remove her from the situation). Ultimately, this situation could also result in calling campus security to resolve the issue.

The Persuasion Sequence is highly effective if used properly. You must make sure to set the full context of the situation, so that you can present people with options. When you appropriately set context for people you “change the reality of the event” for them, as it changes their perspective. When you give someone perspective (perspective giving) it forces them to rethink the position of the other person (perspective taking), and will most likely result in an empathy-driven change of behavior.

Tip: Drawing a blank trying to set the context? Think about what the person has to gain from the situation going well or what they’d have to lose from the situation going badly. If presented tactfully, this reality check could provide just the right amount of perspective they need to change their behavior. Some trainers refer to this concept as “WII F.M.”… the “radio station that everyone listens to.” It stands for “What’s In It For Me.” If you can explain to someone how they’d benefit from a situation, they are likely to cooperate!

Redirecting an Argument

No matter how well intended your conversation is, people still may come at you with verbal resistance. People don’t like to be told what to do, and if you’re asking them to change their behavior, they may in fact “verbally assault” you. The first thing you need to do is keep calm, and remember Emotional Equilibrium, Showtime Mindset, and your hot-button Emotion Guards. But just because you’ve managed to keep your cool, doesn’t mean that the other person will. If you continue to get verbally assaulted and you say nothing to address the situation, you will eventually get angry and leave, or get angry and start screaming back at the other person. Another communication tactic that we teach involves using certain pre-planned phrases that are non-escalatory to deal with a verbal assault. Vistelar calls this tactic, “Redirections.” You can also think of this tactic as “word blocks” — defensive shields to protect yourself from verbal assaults.

Redirections have two steps: 1) acknowledge the tactic and 2) move past the attack and either get back on point or leave.

- Here are a few examples:

- “I appreciate that, however . . .”

- “I understand that; . .”

- “I hear that, . .”

- “I got that; . .”

- “I’m sorry you feel that way, and . . .”

- “Unfortunately, someone gave you some bad ”

- “I can understand why you’re angry and under the same circumstances I would probably be angry However…”

- “I can understand that you don’t like me and that’s OK, but if we get into an argument here… we both lose.”

Note that, in all these examples, the attack is acknowledged but it isn’t addressed. With a Redirection, your message to the other person is that a) you have heard them, b) their attack has no impact on you and c) the interaction must be focused on your agenda, not theirs.

One time I got into huge argument with my best friend. She was really upset and started yelling at me, and she was so upset that she wasn’t really telling me what she was angry about. I was able to get her to stop yelling by saying, “I can see that you’re angry, except I can’t help you if you don’t stop yelling.” That sentence was just enough to get her to stop and think about what she was saying. She then said, “I’m sorry, I’m not angry with you. You’re just the only one here.” That made me a feel a lot better.

Precision of Word Choice

The less time you have to communicate a message, such as in a bystander intervention situation, the more critical it is that you mean what you say, and you say exactly what you mean. One word can make all the difference! This means you need to articulate and remember “Precision of Word Choice.”

Precision of Word Choice simply reminds you to be mindful that even a slight change in word choice can drastically change the meaning of an intended message, as words can mean very different things to different people, as a result of prior experiences, biases, and assumptions. You can clearly see how much a single word can change your meaning by trying a word association drill. Test several of your friends. Tell them that you are going to pick a word, and when you say the word out loud, you want them to tell you the first thing that comes to their mind when they hear it. Try using a word like “fast” or “pizza.” You will be shocked by how many different answers you get! Understanding how words are interpreted differently by other people will help you choose the exactly right words you need in any given situation. Because word choice matters so much, it is important to use when-then thinking and plan out what you would say in a confrontational situation. How would you ask your roommate to turn down the music? How would you support one of your friends who was being pressured to drink? The reason we script out tactics like the Universal Greeting and the Persuasion Sequence is so you can find the right words easily when you need them.

This chapter just serves as an introduction to these important communication skills. Just like any other physical skill, such as hitting a baseball or shooting a basketball, these skills take practice. I highly encourage you to practice these skills any chance you get, and use the online companion to this book to access many additional training resources to help you improve your communication skill set.

“The single biggest problem with communication is the illusion that it has taken place.”

– George Bernard Shaw

.png)