Enjoy this excerpt from one of our published books.

Chapter 7

Uh oh, Cops!

“I’m so glad I didn’t have to do that keg stand. Thank you for stepping in and intervening,” Amanda said to a new friend. “You’re welcome, it was the right thing to do. You looked really nervous,” said Joanna, “I’m glad I could help. Do you want to sit outside and get some fresh air?” Amanda and Joanna left the party and decided to hangout on the front porch of the house. There were dozens of stu- dents outside, some were drinking alcohol, but many were just playing games and listening to music. Amanda looked around, took it all in, and smiled. “I really do love this campus,” she said. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, three police cars pulled up and surrounded the house.

Amanda was struggling to see through the red and blue lights, but she saw several students throwing their cups and running from the house. She even saw a couple students getting chased by the police. Amanda was scared. She hadn’t been drink- ing, but many underage students were. She wanted to run too, but she knew she hadn’t done anything wrong. “Joanna, should we run?” The second she asked the question she regretted it. She was suddenly face to face with a police officer. “Ex- cuse me miss. I’m Officer Thompson with the campus police. I’d like to ask you some questions about this party. Can I please see your driver’s license?” Amanda froze. She had no idea what to do.

There may come a time during your college experience where you will find yourself speaking with law enforcement. Hopefully, it will be because your superior personal awareness skills allowed you to call in a crime that you witnessed. Unfortunately, you may find yourself the victim of a crime and needing to report critical information that could help lead to an arrest. In either case, you will need to know how to be a “good witness” by obtaining the most accurate information possible for the police. Here are some tips about how to be a better witness:

- Take deep breaths, and stay calm.

- Gather as much information about the situation as you If you see subject(s), identify their: name (if known), race, sex, type and color of clothing, body size, hair color, any distinguishing features such as jewelry, tattoos, scars, a distinctive smell, and the last known direction of travel.

- If you see a vehicle, try to identify the: make, model, color, number of doors, license plate, any distinguishing dents or rust spots, and the last known direction of travel.

- If you see a weapon, do the best you can to determine what Was it a knife or club? How long was it? If it was a gun, was it a handgun, rifle, or shotgun?

- If you come across something that looks suspicious, don’t wait to call it in—response time is crucial for law enforcement.

- If you come across an emergency situation with multiple potential injuries, try to identify the number of people injured, their ages, and the extent of their injuries. Are they conscious and breathing? Do they have any gross deformities, or are they bleeding profusely?

Now, it is also possible that at some point you could find yourself in “trouble” with the police. College students usually experience “negative” contacts with law enforcement for actions like:

- Underage drinking/serving a minor/public drinking

- Fighting/disorderly conduct/battery or assault

- Indecent exposure/public urination

- Burglary

- Theft

- Vandalism

- Harassment

- Sexual assault

Recognize that these activities are against the law, and if you are found guilty of perpetrating in any of these activities, they come with heavy fines (anywhere from hundreds of dollars to thousands of dollars!) and possible jail time. So, in the event that you do find yourself interacting with law enforcement as a potential subject of a crime, here are some guidelines for making that interaction as positive as possible, which trust me, is absolutely in your best interest:

- Take deep breaths, and stay calm.

- Keep your hands out of your pockets and make no sudden movements.

- Be polite and respectful—comply with whatever the officer asks you to do.

- Be honest. Do not. Do NOT. Lie.

- Do not try to “butt in” and “be a hero” by defending a friend who got in If you remain respectful to the officers, they will remain respectful to you.

A citizen/law enforcement interaction is generally emotionally charged. If you find yourself being questioned regarding a crime, it will be important to use skills like Showtime Mindset and Emotion Guards and not get overly defensive. Just because an officer has stopped to talk to you doesn’t mean that you necessarily “did something wrong.” Law enforcement officers have tons of different reasons for why they stop and talk to people, and contrary to popular belief, the reasons aren’t always bad!

On a college campus, you will most likely start to recognize many of the campus police and security officers during your first year of school. These officers won’t be like the police officers you encounter off campus, because you will be seeing them and interacting with them over the course of a few years, not just for a brief moment in your life, like during a traffic stop for a speeding violation. And since you will be interacting with them for a few years, I highly encourage you to try and develop the best relationship possible with them. Cam- pus safety professionals are everyday heroes, but behind the badges, they are just everyday normal people trying to help you stay safe. Vistelar Consultant and law enforcement officer Bill Singleton has conducted a substantial amount of work researching police and youth interactions. He has spent a good part of his career developing pro- grams that help foster understanding and collaboration between stu- dents and law enforcement professionals because he knows just how critically important this relationship is to creating a safe environment for everyone. Being an expert on this topic, I asked Bill to write a guest chapter for this book to reiterate these skills and highlight his experience to help you understand the role you play in creating a safe campus environment that everyone can enjoy.

The Moment of Truth

By Bill Singleton

It was a normal September night. Some students were getting settled into their dorms, while others were venturing out to the party scene. It was my third year as a police officer on a college campus.

On this night I was assigned undercover, plainclothes duty. My assignment: underage alcohol consumption prevention. I was to try and detect underage alcohol possession before it led to consumption. Previously, I had worked three years as an undercover narcotics investigator for a different jurisdiction so this assignment seemed rather low key. I was walking with my partner near a well-known intersection when a group of students approached us. They were laughing, yelling and talking loud. More importantly, the majority of the students all had red solo-cups., which likely filled with some type of alcohol. My job that night was to stop them, make sure they were 21, and to educate them on the dangers of binge drinking and college parties. As the group approached, I pulled out my police-issued badge (which I was wearing around my neck) and identified myself as a police officer. The 9 students in the group froze. I asked them if anybody was 21. There was silence. I asked them for the ID’s. Again, nobody moved. I told them that we needed to see their ID’s.

As the students began giving us their ID’s, a male student about 5’ 9”, 140 lbs., looked at me and said, “My friend has my wallet.” I asked him where his friend was and he turned and yelled in a different direction. As he yelled, I made the mistake of turning away from him and looking. When I looked back, he was gone.

The chase was on. He was running so fast that there was no way I was going to catch him. He probably ran about 500 yards before I lost him. I had no idea where he had gone, but I knew he was in the area. We looked and looked for him. After about 45 minutes of looking, he popped up out the bushes (about 15 yards from me) and began running. Little did he know that he was running right into the path of my partner.

My partner (who was also in plainclothes) went to apprehend him, but missed. My partner’s department-issued firearm fell to the ground sliding on the concrete. By the time I reached my partner, he was fighting with the student on the ground and his gun lay exposed to all the students walking by.

After a brief struggle, we were able to secure the student in handcuffs. I was able to secure my partner’s firearm and nobody was seriously hurt.

Good ending for all? Not so fast. It turns out that the student who ran from us, fought with us, and was eventually placed into custody was a star soccer player on the University’s team. He was charged with battery to a police officer, fleeing from a police officer, and underage alcohol possession. His parents, his coach, my partner and I, along with the students and the district attorney, met at the District Attorney’s office to discuss the incident.

During the discussion, the district attorney asked the student why he didn’t cooperate right away. The student said, “Because I didn’t know what was going to happen. I have never had any contact with the police. I didn’t know what to do.” Because the student didn’t know what to do, he panicked. That panic caused him a suspension from the team and academic probation along with 500 hours of community service. He lost his scholarship. Why? Did it have to happen? Could it have been prevented?

The answer is YES! For the last 17 years, I have been a police officer in the State of Wisconsin. I have worked undercover, patrol, community prosecution and in the Officer of Community Outreach & Education. In this last role, my job was to educate the public as to what it is police do, why we do it, where we do it, and how we do it.

My goal was for the public to have a better understanding of who we are so that if they are ever stopped, we can have a conversation rather than the situation I just described.

I’m very honored that Jill asked me to write a chapter in her book about “Police/Citizen Encounters.” I’ve been fortunate to have had the opportunity to be one of the creators of an International Asso- ciation Chiefs of Police award winning program entitled “Students Talking it Over with Police (STOP)” program. Chief Edward Flynn of Milwaukee Police Department came up with this great idea and trusted myself and my partner, Cullin Weiskopf, to create and develop a program that would address the relationship that exists between police and youth with the purpose of decreasing an initial hostile interaction. I have personally delivered presentations to over 2000 students and adults on the topic of police-citizen encounters, and have been on the advisory board for police-youth encounters for the Center of Court Innovation in New York City. In addition, I won The Milwaukee Business Journals’ Top Forty Under 40 in 2012 for my work on the S.T.OP. Program.

Outside of my work as a law enforcement officer, I’ve had the luxury of working with the team at Vistelar. They have helped me grow both personally and professionally. My passion is educating people about what police do and why we do it so that the first encounter they have with police can be easy rather than difficult.

As a student, there is a high probability at some point you will have police contact. That is very important to understand. Just because you are stopped by the police doesn’t mean that you did anything wrong. That’s right. Think about it for a second. If a police officer approaches you and begins asking questions, what is the first thing you think? How do you feel? Scared? Nervous? Anxious? Angry? Confused? Do you immediately think you did something wrong? Do you think that something is wrong?

All of those are great examples of what students have told me about what they’re feeling when stopped by a police officer. And it’s perfectly normal. Heck, when I’m driving in my personal car and a police car pulls behind me, even I begin to get nervous. What did I do? Are my lights out? Am I speeding? And I’m a cop!! I can only imagine what a citizen would be thinking at this point.

In my program created with Vistelar, “Moment of Truth,” we talk about this. We ask students the question, “You’ve just been stopped by the police. Why did it happen? What do you do?” By utilizing the skills you’ve learned in this book from Jill, your encounters with police officers will become more positive.

Every city, town or municipality has their own rules. They are called city ordinances. College campuses have their own rules as well. In the story I told in the beginning of the chapter, one of the rules on campus was that students under the age of 21 were not allowed to possess alcohol. Due to my experience, training, time of night, location, the behavior of the students and the fact that all of them illegally crossed the street (jay walking) I chose to stop them and investigate further. City ordinances or rules are created for public safety. These are situations in which police officers have the discretion to stop you and educate you as to what you’re doing wrong and how you can improve your behavior.

You might be asking, “Illegally crossing the street? You mean we can’t cross the street in front of cars when we have the DON’T WALK signal?” Actually, that constitutes jay walking and you can be stopped by a police officer and questioned. “You mean that I can’t carry a red solo cup and walk down the street at night?” Sure, you can carry the cup, however keep in mind that your behavior, time of night, location, speech, smell of intoxicants all play a factor in determining whether you can be stopped by a police officer.

In the program, “Moment of Truth” we also discuss how suspect descriptions play a role in police encounters. I describe the process and there is a neat interactive game that allows students to learn how difficult it is being a police officer and knowing when or when not to stop a person. And don’t forget, cops can walk up to you and have a casual conversation at any time. But, just because an officer stops you or stops and talks with you it doesn’t mean you did anything wrong. What do you do?

By now you have mastered Vistelar’s conflict management skills, right? Vistelar provides you with a template to overcoming any difficult situation – not just an encounter with a police officer. This time-tested program has been used for over 30 years in law enforcement. The skills are effective and necessary for a productive encounter. I’ve been able to use Vistelar’s conflict management tactics in law enforcement, as a youth coach and as a parent. They are powerful skills and a great addition to anyone’s tool belt.

Vistelar Tactics

If you’re stopped by the police, what happens next? Let’s talk about your emotions. How are you feeling? Scared? Nervous? Anxious? What happens when you get these feelings? Do you begin to zone out and not hear what the person is saying because you’re too scared or nervous? There are five Vistelar tactics you can use to help you effectively manage any difficult situation:

- Showtime Mindset

- Beyond Active Listening

- Universal Greeting

- Redirection

- Showing Respect

Showtime Mindset

The first thing you need to do is to breathe. In the “Moment of Truth” program we discuss having a “Showtime Mindset.” This tactic helps you prepare for the moment. Have you ever given a speech in front of a large crowd? How nervous were you? At some point, you knew that you had to give that speech. You knew you were nervous. While you were getting ready you probably said to yourself, “It’s Showtime!” When you see that officer approaching, you should say the same thing. You know something is about to happen so begin to plan for “Showtime” and understand what your next step will be.

Beyond Active Listening

Second, you should immediately begin to listen to the officer. I talk about this in great detail in the “Moment of Truth” program. At some point the officer is going to ask you a question, so you should be prepared to answer because you know it’s coming.

Listening is more than just hearing words come out of someone’s mouth. Listening involves empathy. If you truly understand where the other person is coming from then that encounter will be much more productive. This is what the “Moment of Truth” program provides to the student. This program shows the student the difficulty of being a police officer and in having to make initial contacts. It shows the student how quickly an encounter can turn bad if handled poorly, how quickly it can turn positive if handled well, and the importance of Empathy in having things go well.. Empathy is defined as the ability to understand and share the feelings of others. Put yourself in the officers’ shoes. How much difficulty would you have going up to a complete stranger and beginning a conversation, especially if you have reason to believe that this person or someone near or around him has committed or is about to commit a crime?

Show some empathy during your encounter and I guarantee that it will change the outcome to a more positive interaction.

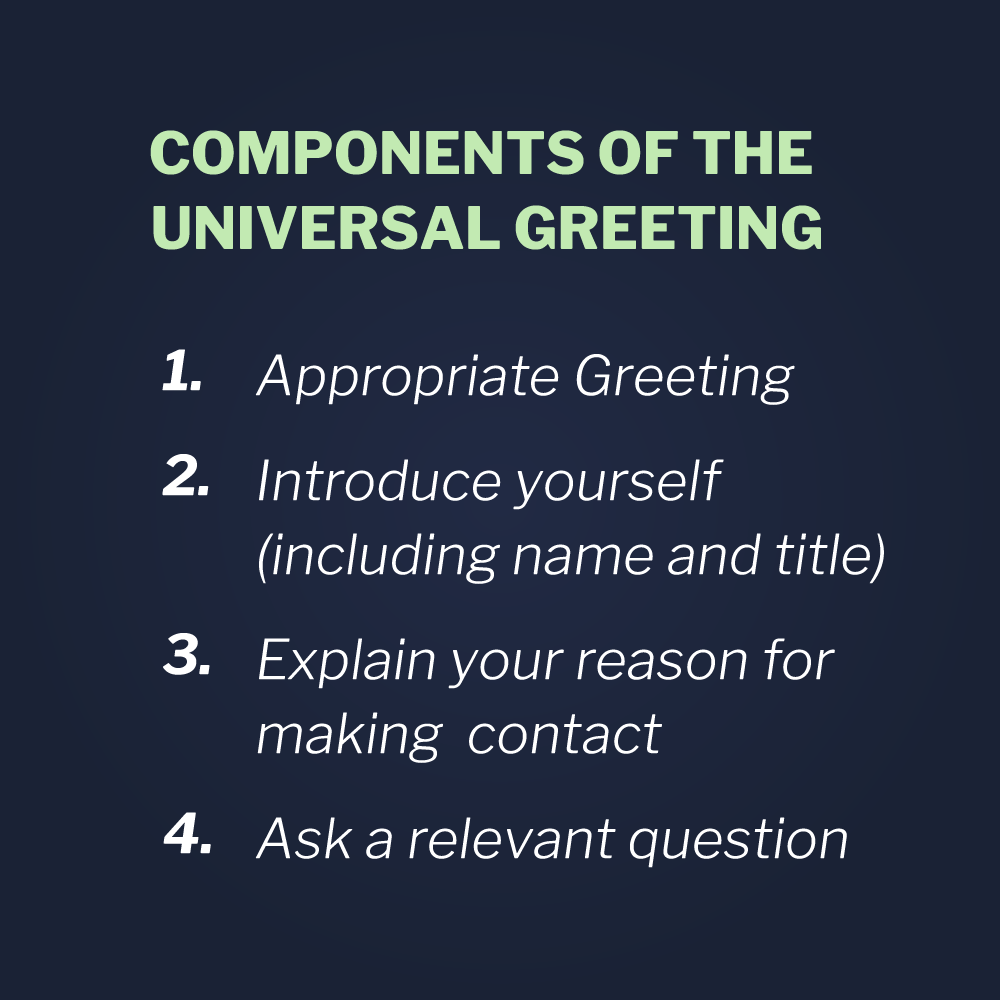

The Universal Greeting

The third tactic you should use when interacting with a police officer is Vistelar’s Universal Greeting:

- Appropriate greeting

- Name and affiliation

- Reason for contact

- Relevant question

Police use this tactic all the time.

Step 1 “Good evening.”

Step 2 “I’m Officer Smith with the Acme Police Department.”

Step 3 “The reason why I stopped you is because I got a report of loitering on this corner.”

Step 4 “Is there any justifiable reason why you’re on this corner right now?”

This is the Universal Greeting and it is vitally important to the initial contact between police and the community. This template provides the officer with a starting point on how to begin a conversation with a complete stranger. In the “Moment of Truth” program we talked about each of the four steps of the Universal Greeting in great detail and explain the power behind each step. This tactic has helped me tremendously in my 17 years as a law enforcement officer. I’ve never been in a fist fight with a suspect and I’ve never had to use pepper spray or my baton on a suspect. I attribute that to the Vistelar conflict management tactics I’ve learned. I’m a defense and arrest tactics instructor and I understand threat assessment. But I also understand that it is a lot easier to deal with someone when you’re not getting punched by them. I’m proud of my ability to communicate effectively with an individual and I believe this ability is one of the most important of the tools I have to manage conflict. Now that you understand why police use this skill, what if cit- izens used it as well? Imagine you get stopped by the police. You know at step 4 of the officer’s Universal Greeting, he or she is going to ask you a question. What if at that moment you were able to flip the script and use the Universal Greeting on the officer.

Step 1 “Hello Officer.”

Step 2 “My name is Tim Johnson.”

Step 3 “The reason I’m standing on this corner is because I’m waiting for a ride and he’s late.”

Step 4 “My identification is in my wallet. Would you like for me to get it for you? Is there anything else you need from me?”

Can you imagine the look on the officer’s face if you were to answer his question with this sequence? Everything the officer needs to know will have been answered in a short time frame because you kept your cool, you listened and you answered by using the Universal Greeting. That stop is guaranteed to be more positive because of it.

The Redirection Tactic

The fourth tactic you will need when interacting with a police officer is the Redirections tactic. This too is a very powerful tool. Redirections comes in many forms; here are three:

- Funny

- Apologetic

- Serious

Redirections are not always needed, but are very powerful if practiced and then used properly. For instance, if an officer approaches you and asks, “What are you doing standing here on the corner?,” you might be feeling a little nervous and want to try to lighten the mood or make conversation by saying:

“I’m sorry officer. I was standing on the corner because I was waiting for a ride. Is there anything I can assist you with?” (apologetic Redirection)

- or -

“Hello Officer. I can tell that something is wrong. I was stand- ing here because I was waiting for a ride. If that is a problem, I can easily wait somewhere else.” (serious Redirection)

In the “Moment of Truth” program, we discuss a variety of Redirections that can be used in everyday life and we emphasize the importance of being prepared.. Practice them so they sound conversational. Redirections are a great tool for getting out of difficult situations.

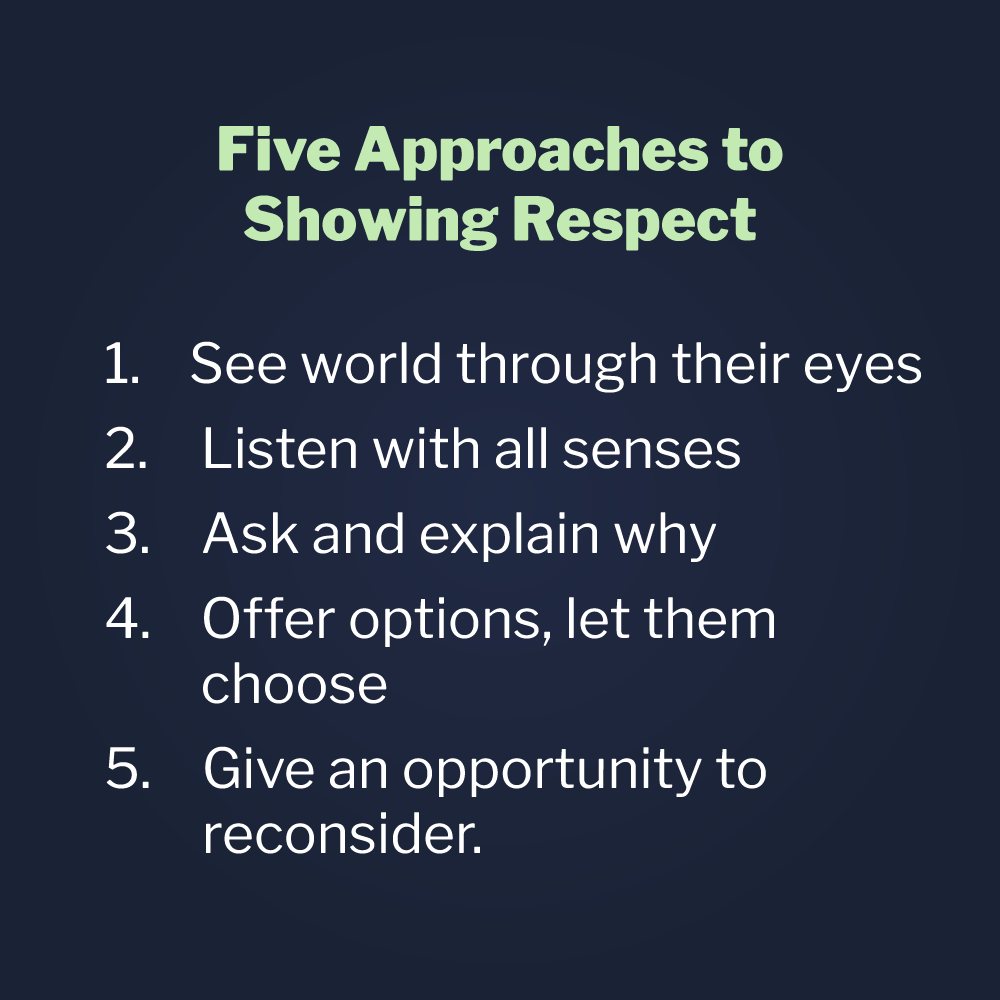

Five Approaches to Showing Respect

The fifth tactic you will need when interacting with a police officer are Vistelar’s five approaches for showing people respect.:

people respect.:

- See the world through their eyes

- “Listen” with all of your senses

- Ask and explain why

- Offer options, let them choose

- Give opportunity to reconsider

If you always try to treat people with dignity by showing respect, I’m confident the majority of your interactions will be positive. By showing respect and having empathy, you immerse yourself into the situation and demonstrate a good understanding of both sides of the interaction. By preparing what you are going to say and when you should say it, your interactions are sure to be more effective.

This chapter provides you with a brief overview on how to deal with police encounters. I provided you with insight as to how police think and talk, tactics you can use when interacting with a police officer. And ways to handle difficult police officers.

I’d like to thank Jill for allowing me the opportunity to be a guest in her great book.

“One of the downfalls of crime prevention training is that you will never know exactly how

many crimes you’ve prevented.”

.png?width=150&height=150&name=Podcasts-%20Newsletter%20Featured%20Image%20Template%20(12).png)