Enjoy this excerpt from one of our published books.

Chapter 6

The Concept of Bystander Intervention

Amanda stood in the kitchen surrounded by at least thirty people, and she didn’t recognize a single one. Paul and Brian were trying to set up the keg and she realized she was going to have to drink or risk getting made fun of for the whole rest of the night. Desperately, she looked around the room to see if anyone cared…if anyone cared at all that she didn’t want to drink. “Outnumbered thirty to one,” she thought, “This isn’t going to end well…my parents are going to kill me.” Amanda looked up, and her eyebrows rose slightly. Jordan had just walked in, looked at her, and shook her head in disgust. Jordan looked at Amanda, looked at the crowd, and then looked carefully at Brian and Paul. “Now what?” Jordan thought.

Jordan was faced with a tough decision at a critical point in time. She could join in the (not) “fun” and force Amanda to drink, or she could help her get out of there and risk being shunned by her peers. Unfortunately, this is a scenario that plays out over and over again on college campuses.

Now that you have learned about concepts such as the Conditions of Awareness, 540 Degree Proxemic Management (for safety), Beyond Active Listening (for information gathering), and the Universal Greeting, Persuasion Sequence, and Redirections (for de-escalating conflict), you have been exposed to all of the skill sets you will need to recognize situations that are going badly and require intervention. You see, “bystanders” actually comprise of the largest number of people in the cycle of violence. Let me put that statement into perspective. If we look at the social cycles of discrimination, bullying, harassment, alcohol abuse, physical abuse, and on up through sexual violence, the number of people, in terms of a percentage, that are actually “perpetrators” of the behavior or are direct “victims” as a result of the behavior, is actually very small in comparison to the number of people who are “bystanders” to the behavior.

Concepts of bystander intervention and ethical intervention are well understood as they pertain to law enforcement and security professionals. They are also commonly understood by managers, supervisors, and disturbance resolution specialists. It’s easy to “sell the need” for bystander intervention strategies to people in positions of power. People in positions of authority generally realize that they SHOULD act and that they have a professional responsibility to act.

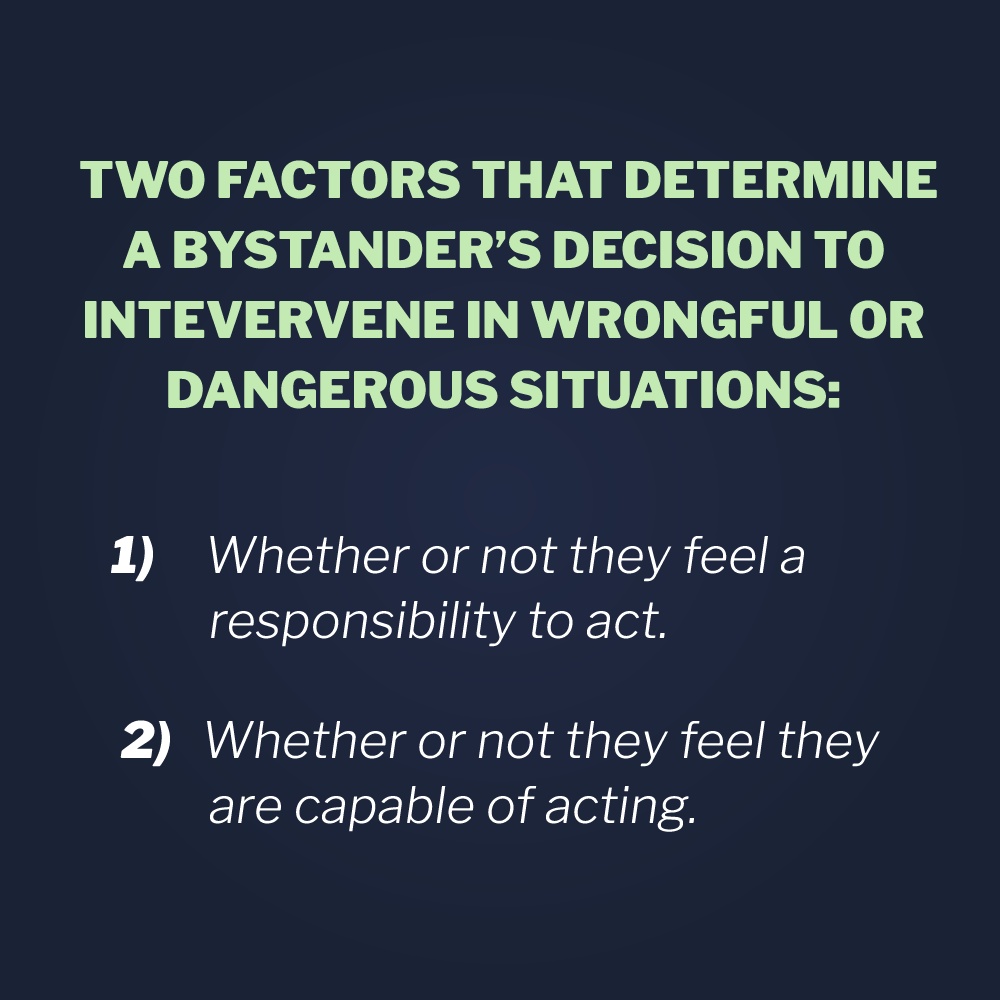

It’s a whole different story though when trying to convince the average student, employee, or citizen to intervene when they become aware of a wrongful or potentially dangerous situation. There are many factors (above just assessing the nature of the offense and whether it would be safe to intervene) that will determine whether or not a “bystander” will choose to step-up and engage in the prevention a potential harmful situation. Research has shown that arbitrary factors such as the potential victim’s attractiveness, or the sex of the person being wronged, will impact a bystander’s decision to act. More so, a bystander’s decision to intervene will hinge greatly upon two factors: whether or not they feel a responsibility to act, and whether or not they feel they are capable of acting.

whether or not a “bystander” will choose to step-up and engage in the prevention a potential harmful situation. Research has shown that arbitrary factors such as the potential victim’s attractiveness, or the sex of the person being wronged, will impact a bystander’s decision to act. More so, a bystander’s decision to intervene will hinge greatly upon two factors: whether or not they feel a responsibility to act, and whether or not they feel they are capable of acting.

Let’s take a closer look at this. First of all, for the average student, employee, or citizen to feel a responsibility to act, we have to assume that they have a “community based” belief system by which they live. Most people aren’t generally motivated to do something for someone else unless there is a specific benefit or reward for them. That should sound familiar, as it is closely related to the “WII F.M.” principle.

In the case of bystander intervention, very rarely is there a specific benefit for the person intervening, other than for them to know that intervening is simply the “right thing to do.” Banking on the belief that “most people will act because it is the right thing to do,” is misguided. Research has shown that when there are several people aware of a bad situation or recognize that a person needs help, the LESS likely it is that they will intervene. Most of the time, it is because of the assumption that “it is someone else’s problem,” or that “someone else will take care of it.”

By collectively mobilizing, engaging, and becoming intolerant of unacceptable behavior (no matter how small), we can prevent the escalation to more harmful and dangerous behaviors. Inappropriate behavior (think: disrespectful language, actions, bullying, predatory behavior) cannot survive in an environment that won’t allow it. We need to create that environment, and we especially need to create that environment on college campuses so that it is a physically and emotionally safe place for everyone to learn, live, and work. The entire campus community plays a valuable role in preventing acts that harm the community or violate basic human dignity.

A lot of people have been asking me about “these new bystander intervention strategies.” “What’s the big deal? Why does this really matter to students anyway?” My direct response is that bystander intervention programming actually matters to everyone, and the concept of helping behavior is far from “new.” It’s easy to think of situations in which a person who is neither the perpetrator nor the victim observes an event and has the power to change the outcome for the better. What these “new” bystander intervention strategies offer are the tools for those observers to actually step in appropriately and safely.

For many people, the problem in understanding “bystander intervention” strategies lies with the word “bystander” itself. “Bystander” literally means someone who is standing by, a witness to, but not participating in. So trying to mobilize people who are “standing by” is a tough concept for people to wrap their heads around. For example, many people, regardless of their work context, witness social injustices such as racial slurs, passive aggressive workplace discrimination, or maybe even not-so-subtle forms of coercion. People who “witness” these things, or who are aware of these behaviors, usually choose not to get involved in stopping the problem by rationalizing that “it has nothing to do with me,” “it’s not my problem,” or “someone else here will take care of it.” This is known as the “bystander effect” and the “diffusion of responsibility.”

The error in this type of thinking is that when people witness events, such as bullying, racism, or dating abuse, they are condoning the behavior they are witnessing. People assume that ignoring the problem, or acting like they didn’t see the problem, will make it go away. The reality is that ignoring the problem does not make it go away, and just like a wound left unattended, the problem will actually grow and possibly become more dangerous. People also assume that since they are not engaging in the inappropriate behavior or are not a direct victim of the injustice, that “standing by” seems like the safest and most “neutral option.” Doing nothing is never a neutral option.

Doing nothing tacitly empowers the perpetrator, and quite frankly, doing nothing is in essence making a choice in favor of the socially toxic behavior further facilitating the creation of an environment that allows it. If you do nothing, nothing changes!

The confusion surrounding bystander intervention goes beyond the word bystander. It also has to do with our understanding of the terms “victim” and “perpetrator.” When we use the nouns victim and perpetrator, we rigidly isolate and categorize people, events, and behaviors. Nouns such as victim and perpetrator are emotionally charged and come with a whole slew of subjective interpretations of what it means to “be a victim” or to “be a perpetrator.” Most of the time, this type of thinking allows us to rationalize and “write ourselves” out of the equation because we don’t categorize or label ourselves as fitting into one of those categories.

With that being said, I challenge you to stop thinking about the cycle of violence as being relevant only to those who are direct victims and perpetrators. I encourage you to start looking at the problem from a different perspective. For example, stop using the nouns and start using the verbs. The term victim refers only to a small percentage of people; however, the number of those who have been “victimized” by the cycle of violence is much greater. I am not a victim of sexual violence, but I have absolutely been victimized by it every time I had to worry if my roommate would make it home ok, when a friend needed my support after being assaulted, and when my campus was profiled in the news as an unsafe place; I am not a victim of workplace bullying or harassment, but I have been victimized by it. I have witnessed how these things affect the lives of loved ones and coworkers, and as a friend, sibling, co-worker, supervisor, and most importantly as a leader, I realize that if I am not part of the solution, I could very well be part of the problem. If you embrace this line of thinking, you will understand why people make the choice to intervene when they see “things going badly.” Make the choice to draw a line in the sand regarding the types of behavior you will allow in your presence, and lets all participate in creating a living, learning, and working environment that is socially healthy for everyone.

The Primary Reasons Why People Don’t Intervene

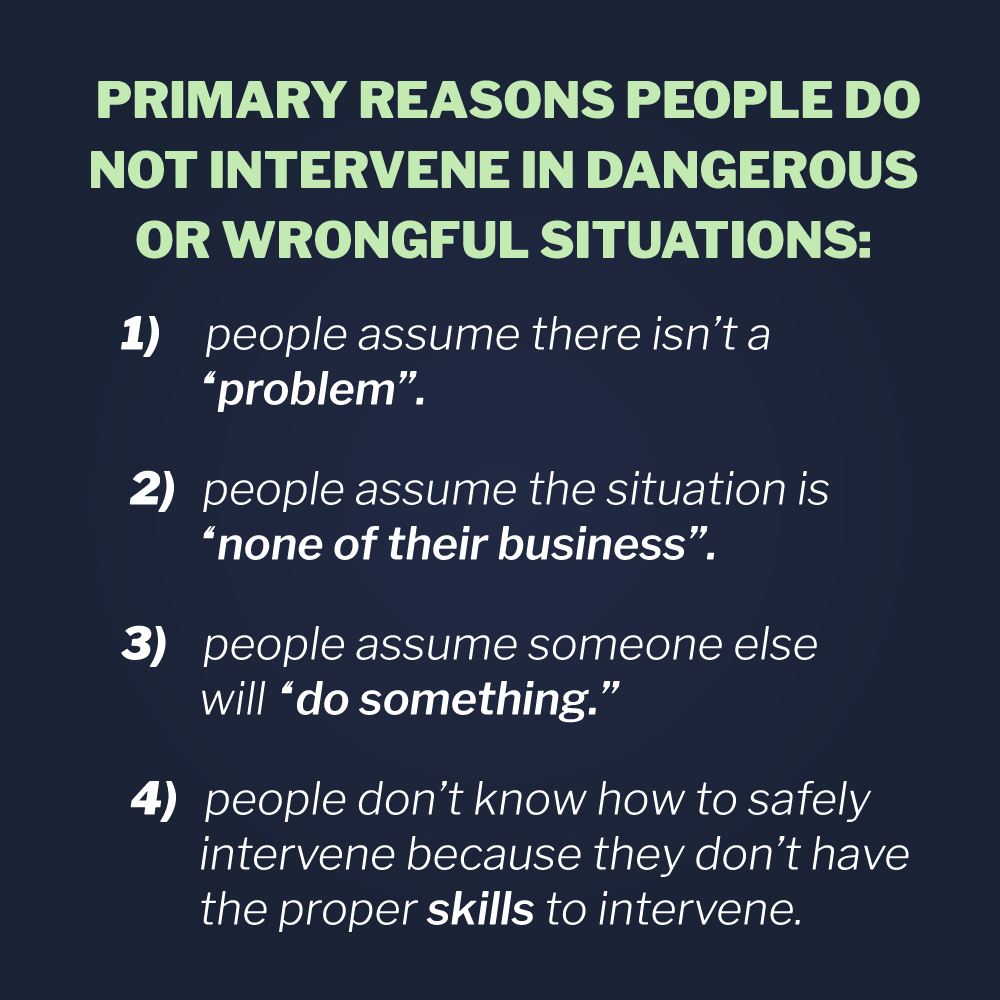

There are many reasons why people choose not to intervene in a situation. Let’s take a look at some of the more prominent ones.

First of all, people will assume the situation isn’t a “problem” and fail to interpret the situation as needing help. If you utilize good risk assessment and threat assessment skills, and learn to identify red flag risk indicators, you will be well equipped to identify a situation as one requiring help.

Most people assume a situation isn’t a “problem” because most situations of discrimination and bullying appear ambiguous. People are generally afraid to inquire if there is a problem for fear that they may be the only one that “feels that way” and don’t want to risk being embarrassed if they are. However, statistics show that when one person steps up, intervenes, or inquires about an ambiguous situation or a potentially discriminatory remark, others are also thinking and feeling the same way.

Second, people assume the situation is “none of their business” and fail to take personal responsibility. Even when bystanders do recognize a problem, most believe that it isn’t THEIR problem, and will choose to ignore it or act like they aren’t aware of it. This is where empathy and perspective taking come into play. Bystanders must ask themselves, “What would I want someone to do for me if I were in this situation?” Usually, the answer to that question provides the bystander with the most appropriate course of action.

Third, people assume someone else will “do something.” This is a dangerous assumption, and is related to a phenomenon known as the “diffusion of responsibility,” whereby each bystander’s sense of responsibility actually decreases as the number of potential witnesses increases. This simply means that most people assume someone else will surely help because other people are there.

actually decreases as the number of potential witnesses increases. This simply means that most people assume someone else will surely help because other people are there.

Finally, people make the false assumption that other people aren’t bothered by the problem, and feel they don’t know how to safely intervene because they don’t have the proper skills to intervene. As stated above, most people are bothered by discriminatory remarks and harassment, but most people lack the communication and social skills necessary to appropriately address the problem. In learning skills such as Beyond Active Listening, the Persuasion Sequence, Redirections, Engagement Phrases, and Emotion Guards, bystanders are better equipped to confidently defuse the situation through conversation. In providing risk assessment skills, assertiveness training, and communication skills, bystanders will have the skills they need to identify problems, mobilize their peer groups, and be prepared to better protect themselves and others.

Here’s What You Can Do to Help: Bystander Intervention Strategies

Bystander intervention should be understood as a life skill. Bystanders who mobilize are known to positively change the outcome of all sorts of situations, including cases of bullying, harassment, and assault. People who intervene can also change the outcome for people who are struggling to get help for things like disordered eating and depression, as sometimes all it takes is for someone to pay attention and choose to show concern.

There is no right or wrong way to choose to intervene, and I am not encouraging you to intervene in a situation that you feel is beyond your ability. If you choose to intervene, do so only when you know you are capable of handling the situation, and you know that you won’t make the situation worse.

However, there are many college bystander intervention programs out there, which teach you how to directly and indirectly intervene, in both emergency and non-emergency situations. Programs such as University of Arizona’s Step UP! Program, the Marquette University T.A.K.E.S. A.C.T.I.O.N. Program, and the Men Can Stop Rape Program are just a few. Below is a summary of the best bystander intervention strategies to come out of those programs.

Presence

Sometimes your presence alone is enough to deter a situation. Think about surveillance cameras in a room; people will generally alter their behavior because they know their being watched, and they know they could get caught. If you are known as a person who won’t tolerate bullying or hazing, the likelihood of it occurring in your presence will decrease. Presence as a strategy is also useful because it allows you to “monitor” a situation from a safe distance. This way, if you’re unsure if a situation requires help, you can observe it and take mental notes of what is going on, in case something does go wrong.

Group Intervention

There is safety and power in numbers. This strategy is best used with someone who has a clear pattern of inappropriate behavior where many examples can be presented as evidence of their problem. This strategy is designed to let others know that they are not alone in their discomfort. For example, you might simply turn to the group and ask, “Am I the only one uncomfortable with this?” This creates options by allowing you to evaluate the situation and recruit the help of friends to determine your best move.

Clarification

People who express negative attitudes towards people expect other people to go along with them, laugh, and join in. They do not expect to be questioned. By asking a question like, “I’m not really sure what you mean by that. Could you explain that to me?” you create the opportunity to either rethink the assumptions that underlie their statements and attitudes or to empower others to express their disagreement.

Bring It Home

This strategy is designed to give perspective to whomever is acting in a degrading manner. It “re-humanizes” their target and makes them think about what it would be like if someone was treating somebody they knew like that. For example, if someone makes fun of another student saying they’re a “total loser” because they have Attention Deficit Disorder (ADD), you could simply say, “Whoa, time out. How you would you feel if you’re brother had ADD? You wouldn’t think he’s such a loser then.”

“I” Statements

Think about how you feel when someone points the finger at you, and someone says in an accusatory voice, “YOU really need to stop acting like that, you’re embarrassing the family.” Instead think about how “I” statements are easier to hear since they are about the feelings and thoughts of the person making the statement, and not criticizing and accusing the other person. People are less likely to become defensive when using “I” statements. For example, you could say, “I find it embarrassing when you act like that. I’d like it if you could change you behavior in the future.”

Humor

Humor is a difficult strategy as it can easily escalate if people feel they’re being mocked. However, if you use humor effectively, it can reduce the tension inherent in the interventions and make it easier for the person to hear you. Be careful, though, not to be so funny that you undermine the point you’re trying to make.

Silent Stare

This strategy works very well if you connect it to parents, who have the ability to communicate displeasure simply by staring. No words even need to be spoken. Sometimes a disapproving look can be far more powerful than words. Think about a time someone you really respected just looked at you and shook their head in disapproval. Remember how awful you felt?

Distraction

The goal of this strategy is not to directly confront the situation, but rather to interrupt it so that you change the course of it. This is an especially useful technique where there is a higher risk of physical violence, like a fight in progress or when there are multiple actors and only one of you). Use a distraction to redirect the focus somewhere else, or to draw their attention away from their target.

“We’re Friends, Right?”

This strategy works best if you can take your friend (or another person) off to the side or if you can wait until later to confront them. That way, you can avoid humiliating them and increase the likelihood that they will hear and value what you say. For example, if you overhear a friend say something awful about another friend, you can talk to them after the fact and say, “Hey, we’re friends, right? I don’t want to fight with you, but I didn’t like what you said about Tom earlier.”

Cut and Divide

Step in and separate the two people and recruit help to do this if need be. By separating the two people, you can help them “cool off ” and you can avoid them trying to posture or escalate in front of their friends. Don’t use this strategy where you’d face a high risk of physical injury.

Take a Picture

Have a camera phone? Use technology to your advantage. People immediately sensor their behavior when they know they are being recorded! It is now easier than ever to record good witness information for police. Notice a security camera? Politely point it out to the person who is acting up, and remind them that it’s not worth getting caught.

Engagement Phrases

Now that you have a solid understanding of bystander intervention strategies, you’re starting to see all of the options you have to help yourself and others if you hear something inappropriate or see something going badly. Most of the time, however, it won’t be enough just to know what to do; you also have to know what to say. If you recall back to some of the communication strategies you learned about earlier, you will remember the “Redirections” that you can use to change the course of a confrontation. Like Redirections, “Engagement Phrases” are phrases you can use to quickly inter- vene and get the attention of the other person. Engagement Phrases should be short, quick, and just long enough to tactfully get your point across without escalating the situation. If you use an engage- ment phrase to get involved in a situation, just remember that you have to match your verbal and non-verbal cues to “sell” the state- ment. The phrase must be delivered both verbally and non-verbally as non-escalatory and non-judgmental.

Here are some examples:

- “This is ‘X-school.’ That is not what we are about. ”

- “I hope no one talks about you like that.”

- “The team needs you and expects more from you. ”

- “You may not have offended me, but your words/actions/ behaviors, may have offended someone else.”

- “Could you please clarify what you just said? I’m not sure I understood that correctly.”

- “I know you are better than that.”

- “Wow, do you really feel that way about ‘x’ person/group/behavior?”

- “I didn’t expect that from you. ”

- “We’ve always been able to work things out in the past.”

- “Would you work with me here?”

- “This is good for you, good for me, and good for everybody/the team/ this school.”

- “Please leave with me. I have a concern for our safety.”

Bystander Intervention Tips

As a bystander witness, you don’t have to intervene directly (such as talking with the person immediately). You can choose to indirectly intervene by speaking with another person who you feel could be helpful in addressing or resolving the issue after the fact (such as a friend, teacher, coach, administrator, counselor, etc.)

If you do recognize a problem and choose to respond, try and remem- ber the following tips adapted from the ‘University of Arizona’s Step UP! Program’ that utilizes Vistelar conflict management principles:

- Investigate an unclear event further, and/or ask others what they think of the situation.

- Know your limits as a helper—engage others as necessary. Ask yourself what could happen if you don’t intervene, and determine if there’s someone else better equipped to help. Don’t unnecessarily put yourself in danger! Quickly decide if the situation is a concern for safety, or a concern for life. This will help you determine if the situation is an emergency, or non-emergency.

- Be mindful of peer pressure and be prepared to respond to it. Not everybody intervenes; if they did, we wouldn’t have to talk about bystander intervention. Some people may question why you’re trying to help another person, or why you’re going against the grain. Use it as an opportunity to set context for them and change their perspective.

- Conduct conversations in a safe environment. Maintain mutual respect and mutual purpose. Be mindful of the “greater than, less than, and equal to” concept, and reflect that in your tone. Try to develop the right atmosphere for positive communication so that you don’t inadvertently come across as accusatory, which would result in a defensive reaction.

- Remember that how you say things is more important than what you When forming your intervention conversation, be mindful of: Who (you’re speaking to, or who is all involved), What (the exact content of what you want to say—utilize Precision of Word Choice), When (how you time the delivery), Where (you have the conversation, consider the location and level of privacy), Why (the reason you are talking with them) and How (tone, pace, pitch, modulation, and non-verbal behavior).

- Consider the frequency, duration, and intensity or/severity of the behavior when evaluating a situation and determining the best way to talk about it. Does this behavior happen often? What is the result of the behavior? The answers to those questions will help you determine WHAT to say, HOW to say it, and WHEN you need to intervene.

- Be sensitive, understanding, and non-judgmental. Utilize Beyond Active Listening and an empathetic presentation style, both verbally and non-verbally.

- Determine the priority outcome goal. What is the behavior you are hoping to stop? And what is the behavior/outcome you are trying to encourage? With those answers, you can formulate a plan and prepare/practice what you want to say.

- Be creative! Interrupt/distract/delay a situation you think might be problematic—before it becomes an emergency!

Post-Action Aftermath

Whether you choose to intervene in a situation or not, you may find yourself in a position where you have to relay information to the authorities. Using the skills outlined in this book will undoubtedly make you a better witness and improve your ability to relay accurate information to the police. If you intervened in an emergency situation, such as a multiple injury car accident, you may find yourself a little “shook up” from being involved in something you’ve seen before.

After the incident, especially if you had to get physical, take a quick self-assessment. Are you physically OK? Check for injuries. Did you get hit in the head? Then you will most likely want to get checked out. Are you mentally OK? Take a few deep breaths, slow down your thinking, and drink a glass of water. Taking some time to process what happened is good psychological first aid, and it will help you relay accurate information to authorities. In addition to police and security, be prepared to explain what happened to your family and friends, as they will likely have questions and want to hear about what you did. You may have to explain all of the things you saw and heard that lead up to the event. Thinking all of those things through will help you understand and justify your “reactions” to what happened.

What About Self-Defense?

I couldn’t write a book on campus safety and not acknowledge the need for self-defense training. As you’ve learned throughout the book, things could get physical at any time. If the “fight” comes to you, you need to be prepared to defend yourself. Take a minute to assess your physical fitness level and your overall physical ability. How much confidence do you have in your ability to defend yourself if your life suddenly depended on it? Some of you may have extensive self- defense and/or martial arts training, and some of you may have none at all. Even if you have some training, I encourage you to seek out additional training and learn new skills. You can never have enough training. Check to see if your campus police or campus security offers training. Many times, colleges will host self-defense classes with little or no cost to you. Can’t find a class close? Give us a call. We can bring the training to you or your school!

“The world is a dangerous place to live; not because of the people who are evil, but because of the people who don’t do anything about it.”

– Albert Einstein