“Psychomotor Skill Training: How to Optimize Learning”

(This is the first episode in a two-part series. To listen to the next episode click here.)

In this episode, Allen Oelschlaeger is joined by Gerard O’Dea from Dyna

mis (https://www.dynamis.training), a UK conflict management training company and Professor Chris Cushion from Loughborough University (https://www.lboro.ac.uk/departments/ssehs/staff/chris-cushion), a renown expert in how to teach psychomotor skills to optimize learning (conflict management skills are psychomotor skills).

Gerard and Professor Cushion have been working together for the last six years to develop a training system that creates a relatively permanent change in their student’s behavior that results in the benefits Dynamis promises its customers (healthcare, education, law enforcement, residential care).

The discussion focuses on the core training principles validated by empirical research over the last 40 years that produce these outcomes. Also discussed is how these principles are so rarely applied in the training of psychomotor skills.

Some of the core principles discussed include:

- How the goal of a training program is learning (relatively permanent change in student’s behavior that supports the results expected from the training) rather than getting positive reviews

- Training must use whole task scenarios in order to optimize learning (instead of block training of small elements of the whole task that only create the illusion of learning)

- The whole-task scenario must reflect real-world situations faced by the student (instead of the skill practice being decontextualized).

- Training should be structured to take advantage of the background and experience that the students bring to class

Host: Al Oeschlaeger, Vistelar

Guest: Gerard O’Dea and Professor Chris Cushion

Subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Google Play or YouTube

Al:

Well, good afternoon. We already know we have a couple of outstanding folks from the UK on − Gerard O’Dea and Professor Cushion. So, guys, why don’t you introduce yourself and then we can start the talk.

Gerard O’Dea:

I will. It’s Gerard here, currently from the Lake Districts in the UK where I’m recording this with Al and Chris. I’m the Director of training at Dynamis. We’ve been providing since 2006 conflict management training, physical intervention training, and all of the advice and guidance that goes around that. My interests really at the moment are about how we ensure that learners take those skills that we’re teaching them in the classroom and can apply them as efficiently and powerfully back in the workplace as they can to do things like reduce the amount of restraints that they’re doing, to make the restraints that they might be doing safer. If we’re teaching law enforcement officers or security, that we’re creating better outcomes in their environments and we’re going to try to do that through achieving better learning and that’s where I met and started collaboration with Chris, who’s also on the call today.

Al:

So Chris, Professor Cushion.

Professor Chris Cushion:

Yes. Good afternoon. I’m Professor Chris Cushion. I’m a Professor of Coaching and Pedagogy at Loughborough University, and before everybody has to look up what pedagogy means, it just the means the science of instruction. Simply how the learner, the curriculum, and the environment come together to create a learning environment. And that really is my research interest and research background. I predominantly worked in the sporting environment where I’ve been looking at coach behavior, practice design, and an understanding of learning and how that comes together to create a learning environment, so it’s very much based in a sporting environment predominantly. But more recently I’ve started to work in other domains where people have to perform under pressure, that includes the military and law enforcement.

Al:

Professor Cushion, you and I met and-

Professor Chris Cushion:

Yes.

Al:

… when we were over there doing a week-long class back in December. Spent the night with, we had a little Airbnb-thing, and we all spent the evening together.

Professor Chris Cushion:

Yes.

Al:

But I was just amazed by the size of the department you have that’s focused on this. So, share just a little bit about how many PhDs you have and staff and who you interact with. I know you’re involved with some of the UK soccer teams.

Loughborough University Coaching and Pedagogy Department Background

Professor Chris Cushion:

Sure. So, I currently have five PhD students working in this space, recently graduated two in a month, which was good. They were working in high performance coach education in the UK so with an organization called UK Sport and looking at the design and delivery of the highest level of coach development. The other PhD student was looking at working in Paralympic coaching, so working with people having disabilities but again, in the Paralympic environment. So, I’ve got about five, well five or six, PhD students now in various roles. We’re engaged with a range of projects looking at all of these issues and questions. One of my, let’s say most extensive or interesting clients, Leicester City, who are former Premier League champions, but we helped structure and design the coach education and development for their academy staff which is about 35 coaches currently. And I work in the School the Sport, Exercise and Health Sciences which has 120 staff. So we’re one of the largest staff, one of the largest departments or schools in the UK in this area of study.

Gerard O’Dea:

I have to admit to working from my home office this evening and my very, very boisterous, young fellows are making a little bit of noise in the room next door here, Al, but I believe they’ll settle down shortly and if not, I’ll be using some very skillful conflict managements to get them to just tone it down a little bit.

Al:

Well, it’s the reality of the pandemic world. I think we’re all living with this where everybody’s at home and, yup, you just got to live with it. So, Professor Cushion, you told me also that, I think I asked the question, I said, who else is doing this research around the world and obviously you think you’re doing some great work there, but I think you do feel like you have the leading university on the planet working on this kind of stuff, right?

Professor Chris Cushion:

Well, it’s interesting. So there’s an interest in learning in skill acquisition and there’s lots of people doing that work all around the country, in the UK and overseas. There’s some pretty well established principles that people discuss and talk about and that they are becoming, even though they have been around for 30 or 40 years, they are becoming increasingly more publicized and starting to creep into different training environments and different cultures. But my own research, there aren’t that many people who have kind of moving beyond that and really being up-to-date evidenced informed and contemporary in their way of looking at it. I think, I was recently asked on Board the College of Policing in the UK to sit on their strategy Board for the redesign of their police officer safety training system, their curriculum and course design. And I am 50% of the research in that space in the UK, and the last research of the meet was done in 2007. So I am the research in that space which is a little uncomfortable for me to say at times, but unfortunately, that’s the way it is.

Al:

Yeah. Well, the two of you worked together, what? Has it been six years? Is that about right?

Gerard O’Dea:

Yeah, it’s about that. I was running from time to time instructor programs here in the UK for people interested in learning trainer level skills really in teaching functional tactics for self-protection, personal safety, and things like control tactics and whatnot. And I think during that time, Chris was embarking on some in-person, sort of experiential research on what was happening in that market. It was one of the interests that took him. And Chris ended up on one of my courses. I think it was in Edinburgh?

Professor Chris Cushion:

It was, yup.

Gerard O’Dea:

And, that’s where we started having these conversations, I think, about how to create real learning.

Creating "Real" Learning

Professor Chris Cushion:

I mean, from my perspective, I guess, obviously I have a sporting background, but I have a martial arts background so I instruct in jujitsu and I help out at a couple of clubs in my local area, as well as train. And I was intrigued by different types of people coming in for the classes, so including police officers, people who are first responders who just wanted additional training were hunting around for something different. So that kind of piqued my interest in the type of learning environments that they were receiving and the type of training they were getting. And my background as a researcher is, I’m an ethnographer and all that means is, ethnography is just a picture of a way of life. So to understand something, I feel the need to be immersed in it so I am a participant observer. So I basically set out, knocked out a program of research where I said, okay, I’m going to do some research and find out what’s going on in these different environments. Let’s look at the training, let’s look at the environments that are being set up.

Professor Chris Cushion:

So I basically enrolled myself on a number of courses around self-defense, around secure mental health, around law enforcement, around special educational needs, and different types of courses and different types of conflict management, control and restraint, breakaway, however you want to term it, and just enrolled on the courses essentially to collect data and go through those courses as a learner and, fortunately, one of those was Gerard’s course. So I collected some data on his stuff and we got to talking about the type of training that he was doing and it kind of went from there.

O'Dea's Background

Gerard O’Dea:

So, Al, my place in the market I suppose was really influenced by time I had spent studying in the U.S. Which was a kind of interesting twist on this story is that, I had been to the Northwest Training College which I know you guys at Vistelar have a connection there and NWTC.

Al:

Yup.

Gerard O’Dea:

I’ve been through Virginia Beach. I visited the training facilities and experienced some of the training methodologies in the U.S., including going to see you guys at Mall of America back in 2014. And that exposure, that sort of stepping outside of the bubble, the comfort zone here in the UK, really taught me that I should be looking at different approaches and how do we teach conflict management and physical interventions and so on. And that’s what kind of differentiates what we do as a company here in the UK is that we do take the different approach and try to give maximum value to both our clients and our learners.

Gerard O’Dea:

And I think then when Chris came along and saw what we were trying to do, that became the basis then for some really great conversations and I can talk a little bit in a while about how one particular conversation that Chris and I had really changed the game for us. But, again, it just boils down to being able to look at sort of different approaches and focus on what the learner needs, rather than staying focused on, what’s my curriculum and sort of staying in that safe zone.

The Psychomotor Skill Training Business

Al:

Well, at the end of the day, and Gerard, you know I think about this stuff a lot because I mean we talk about it being psychomotor skills. We’re in the psychomotor skill training business. We’re not teaching math or accounting or social studies. I mean, this is, at the end of the day, people need to take what we learn, they have to go out in the marketplace, and they have to interact with real people, and people are in their face or whatever, physical, verbal, whatever is going on, and they have to use the skills appropriately. And they got to use them over time. And the ultimate goal is, they got to then actually have an impact on their business where the benefits that we are looking for actually happen. And that requires training that is much different than what historically has been going on. And, Gerard, you have told me before meeting Professor Cushion, you taught in a certain way and you changed pretty dramatically, I think, right, from what you were doing to what you’re doing now. So-

Gerard O’Dea:

Absolutely. I think there was two key interactions and I’ll ask Chris to chip in here in just a second with what he saw. But, the first interaction we had where I really realized we needed to change up how we were doing was when Chris was talking about activity during a training course and, specifically, things like instructor-talk time and so on. And he suggested, “Well, I could come along and maybe watch one of your training courses and do an audit on how you do it.” And I said, “Yeah, sure, fine. I’m doing pretty well. I’m really confident. My learners give me great smiley faces at the end of my training courses and they tick all the boxes and say we’re excellent and so on.”

Gerard O’Dea:

And then Chris came along to a training course I was delivering on positive handling in the school and he audited the course and he has a specific way of modeling behaviors for coaches and so on. And I don’t know if he remembers exactly what the results were, but when he presented them to me later on, it was really striking that I thought I was doing some really good training, but the data that he collected that day really didn’t support my assertion that I was good at what I was doing. And it was a real wake-up moment for me and one which deepened my interest in what he was saying.

Professor Chris Cushion:

Yeah.

Refining Core Principles

Al:

And so Why don’t you, you guys have been through this for the last six years. Gerard, you had obviously your experience prior to meeting Professor Cushion. You’ve now adopted a lot of what he has been doing research on for the last six years, you’ve refined that. So just between the two of you, share some of the core principles that you now apply and why they work and why it was different than what you used to do, Gerard, and let’s get kind of in depth what this looks like compared to maybe what people are used to.

Gerard O’Dea:

Chris, do you want to lead on that so that people can get the raw principles and some of the key ideas?

Professor Chris Cushion:

I think just picking up on your point, Gerard, around an important proxy for learning is time on task. If we can measure the outcome, then we can measure the process and we can see how things end up but it’s actually quite difficult to capture in learning. But a proxy for learning is time on task, so one of the basic audits that I will always do is, what is the experience of the learner, what are they spending their time doing. So if you want them to learn X, they need to be spending most of their time doing, practicing, thinking, about X. And invariably, at least half the time, they’re not. So in the audits I’ve done, and it’s reasonably consistent across industries, about 50% of the time they’re not doing that. They’re doing other things. Very often, they’re standing around hearing, listening to war stories, and being talked at by instructors rather than being coached or practicing the task. So, that’s the first observation.

Professor Chris Cushion:

I guess there’s a, as you said, it’s across a range of domains, not necessarily control and restraint or any of.png?width=250&name=Vistelar-Podcast-Psychomotor-Skill-Training-Pt-1%20(2).png) those areas. There’s a dominant training paradigm, I learned this in sport as well, where we basically block, or we start with a linear approach or a feels-first approach, and it’s generally disintegrated training. And what I mean by that is, we take a whole thing, we slice it into smaller bits, we start with the most basic bit, we do that until we’ve got it, and then we add another bit and then we add another bit and then we add another bit, and at the end, we’ve reassembled the whole. And then we take the whole and then we put it in some kind of context.

those areas. There’s a dominant training paradigm, I learned this in sport as well, where we basically block, or we start with a linear approach or a feels-first approach, and it’s generally disintegrated training. And what I mean by that is, we take a whole thing, we slice it into smaller bits, we start with the most basic bit, we do that until we’ve got it, and then we add another bit and then we add another bit and then we add another bit, and at the end, we’ve reassembled the whole. And then we take the whole and then we put it in some kind of context.

Professor Chris Cushion:

Now the research evidence tells us that that’s not actually, it’s great for performance. So people who practice that way are able then to perform that so in much the way that people learn a script, like deliver it, actors learn a script or they perform a script, they don’t learn a script. So that’s really good performance but not good for learning so people find that really difficult to retain and in tests six weeks, eight weeks, two months, a year later, they basically haven’t learned the stuff so they give the impression that they’ve learned it, but they haven’t. And those feelings in learners, they’re very poor at conceptualizing their own learning. We misjudge feelings of performance for feelings of learning. So if you practice something over and over again, and then do it, we convince ourselves that we’ve learned it, when in fact we haven’t.

Al:

And do you know that because, is there a why behind that as to kind of why that’s the case, that this practice drill approach doesn’t work and doesn’t produce long-term learning, or is it just you’ve now, based on research, know that it doesn’t work?

Reinforcing a Feeling of Competence and Confidence in Learners

Professor Chris Cushion:

Well, based on probably 40 years of research, we know it doesn’t work. I mean, what’s really interesting is, I would never take the drill, the block practice things out of my training. I would never do that. But I would think really carefully about how I apply them. So what block training does give us is gives us feelings of competence and it gives us feelings of confidence. And that gives us these positive feelings saying, I must have learned that. But, of course, when we train people, we need them to feel confident and we need them to feel competent. So the way that we learn is, it’s almost counterintuitive, so if we do it in small chunks and we do it a bit at a time, we start very small and we build it and then we put into context at the end. It helps us feel competent and it helps us feel confident. But, under pressure, however, that learning will collapse.

Al:

Wow. And when you say, 40 years of research, you’re saying that people have tried that approach and sure enough, a year later, people forget stuff. Where if they try the time on task and whole task approach, a year later, they’re able to apply the stuff more…

Professor Chris Cushion:

Yup. That’s learning something that you’ve learned, right? You’ve learned to tie your shoes. You don’t forget how to do it.

Al:

Right.

Professor Chris Cushion:

You’ve learned it. You don’t have to relearn it. You don’t have to… There’s no such thing as over-learning. Once you’ve learned it, you’ve learned it.

Al:

Yup.

Professor Chris Cushion:

I mean, the more complex the task and the more difficult it is, obviously there’s issues of memory and those things fade, so there is such a thing as skill fade. But my argument very often is, you probably didn’t learn it in the first place. You performed it in the first place. You didn’t learn it. So stuff that’s truly learned… You could not drive a car for 10 years, and for the people in the U.S., a stick shift, if you’ve learned to drive a stick shift, you cannot drive one for a decade and get in and be able to drive it. You don’t forget. You’ve learned it, haven’t you? It’s not a performance because you’ve got enough repetitions in context, it’s become part of who you are and what you are able to do. So there’s a real difference around that. So that’s not to say that we still need to practice particularly stuff that’s more complex or more difficult. That will fade if you don’t use it. But it all depends on how it’s learned or how it’s practiced in the first place. I mean-

Al:

But, Gerard, that’s your… And now I understand better. You told a story of, I think, early on you spent four or five days with that mobile transport group and you can share it.

Effective Results - Mobile Transport Group

Gerard O’Dea:

That’s right.

Al:

And then you went back like a year later and you know that they actually didn’t have a lot of opportunity to apply that for whatever reason, but they still knew it.

Professor Chris Cushion:

Right, that’s-

Gerard O’Dea:

Yeah, it’s absolutely true. And one of the things that was… so I’ll explain a little bit more with that in a sec. One of my favorite ways of explaining the difference between learning and performance is, and I think Robert Bjork who is a sort of giant in the field, said, “It’s a bit like cramming for the test. And when you cram for the test, you might be able to get over the test, but you’re probably not retaining any of that information or skill a week, or six weeks, or six months, later.” And so, when you kind of bring something on board really quickly, you also forget it really quickly. And if you bring something on board really easily, then it’s probably not going to stick. And one of the things there is about making it difficult, which we can come back to, making the learning just that little bit messy.

Gerard O’Dea:

But yeah, the team I met was a secure escort team. They were just newly assembled and I went down there to teach them and I taught them using a methodology I had worked out with Chris, with Chris’s input. When I went to him one day, I said, “Look. These guys have a really varied job. They meet all kinds of different people and they can meet all kinds of people who present all kinds of different risk.” They can be everything from incredibly compliant and easy to work with, to very, very distressed and upset, frustrated, maybe even delirious, hallucinating, and trying to escape from their vehicle and run across several lanes of traffic, or even steal their vehicle from them and go ahead and crash it, which is a real story that happened to one of these teams.

Gerard O’Dea:

So Chris gave me a suggestion to work on an increasingly complex version of the whole, which he can talk about here in a second. And we kind of worked up over a cup of coffee or three, a way of teaching these teams that would be an increasingly complex version of the whole. And I went and taught that to them over a period of four days, I think it was. And just like you said, Al, I went back through a refresher training with them a year later and, unfortunately, the way things had worked out for that company, they hadn’t actually done any interactions, they hadn’t actually transported anybody in that role or of that nature. And we went through the refresher training and they were really, really good. I mean, they were replicating the skills that they learned at a very high level of fidelity to what I had shown them. And it really proved to me that the way we do it with the kind of desirable difficulties and with the just hundreds or reps that we get in, the way we do things, it really helped them to learn the material.

Al:

So the point being that they did actually, using Professor Cushion’s term, they learned it. It was embedded in them. A year later they could still do it, and versus, again Professor Cushion’s term is performance, meaning that you’ve maybe right at the end of training, you felt confident and competent you could do it because you drilled it. But a year later you wouldn’t be able to do it because you didn’t really learn it. Do I have that right?

Gerard O’Dea:

Absolutely. There’s this one thing that I would add to that which is, again, a really great description of that that I saw is, a lot of the training that you see right now and just the way that people have developed very risk-averse training and very neat training that can be easily delivered, is show me what I just showed you. That’s what the instructor is kind of expected to do. The instructor is expected to demand that the learner show them the thing that they just got shown.

Al:

Yeah.

Why Traditional Methods Are Not Better

Gerard O’Dea:

And that’s really for the learner to then perform that task. You know, monkey see, monkey do?

Al:

Right.

Gerard O’Dea:

But I think what Chris would tell you is that, that’s not going to develop any great learning.

Professor Chris Cushion:

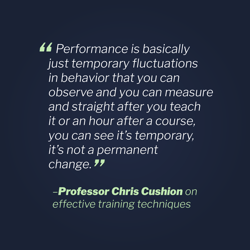

Right. And I think, I mean, when we talk about learning, we’re talking about something that’s a relatively permanent change that supports retention and transfer. So something’s changed that means that you’ll retain it and transfer it. So the training room isn’t the real world so it needs to transfer out of the training room and into the real world. But it also needs to be retained, i.e., you need to be able to do it in six months’ time or a year’s time. And performance is basically, as Gerard said, it’s just temporary fluctuations in behavior that you can observe and you can measure and straight after you teach it or an hour after a course, you can see it’s temporary, it’s not a permanent change. And it isn’t retained and it doesn’t transfer so those are important differences.

permanent change that supports retention and transfer. So something’s changed that means that you’ll retain it and transfer it. So the training room isn’t the real world so it needs to transfer out of the training room and into the real world. But it also needs to be retained, i.e., you need to be able to do it in six months’ time or a year’s time. And performance is basically, as Gerard said, it’s just temporary fluctuations in behavior that you can observe and you can measure and straight after you teach it or an hour after a course, you can see it’s temporary, it’s not a permanent change. And it isn’t retained and it doesn’t transfer so those are important differences.

Al:

Okay, so you’ve said there’s 40 years of research supporting this?

Professor Chris Cushion:

Yup.

Al:

I’ve been to a lot of training over the years, various things. I haven’t seen a lot of this. So why is that?

Performance vs Learning

Professor Chris Cushion:

It’s a great question. I mean, the performance, the difference between performance and learning, the first research was done, I mean it’s nearly 100 years old. Late ’20s, I think people started to look at latent learning and the difference between learning and performance, so that research is well established. And we’re looking at easily the ’70s when we first start to look at these experiments and research that looked at this difference between what environments create learning and what environments create performance. I don’t know how evidence-informed our particular places. My own experience is there becomes a traditional way, there’s a perception of things, of what works. I mean, Gerard’s example is good. He got great reviews, his clients were coming back, it’s all great, the questionnaires, this is great training. And again, people misrecognize the feelings of performance, the feelings of learning. They give good reviews. So why would you change? If you think what you’re doing works, why would you change it? Until there’s concrete evidence or a concrete challenge to your belief that this isn’t working, why would you ever change it?

Professor Chris Cushion:

In my experience, the trainers I’ve come across are all incredibly knowledgeable, they’re all incredibly experienced, they’re great operators. They know so much, but they’re ultimately convinced what they do works and there’s no evidence to counter that. Because it’s very easy to… You watch a video of conflict to where it’s gone wrong and the trainers can talk away the problems with the parts on the video. They very, very rarely ask the question, well actually it was the training that didn’t prepare this person. So there’s a whole range of reasons why, if you think your training works, if you’ve developed a way that you think works and you get feedback that tells you that it does, why would you need to listen to anything else really?

Al:

And I-

Gerard O’Dea:

If I could jump in? Sorry. Al, in the UK, we have a real push towards evidence-based practice and research-informed training course design and so on and when we, when Chris and I sat down to look at some of the research in healthcare, for example, what it showed is that, people have looked at training over the years and what it’s outcomes are. So they take people who haven’t had training and then they train them, and then they look at how they do things afterwards. And some of the conclusions that they’ve come to are that, oh, training isn’t that effective. Or, this training, it doesn’t work. Or, we shouldn’t do that kind of training because the research doesn’t show that it moves the needle on the workforce floor.

Gerard O’Dea:

But when we looked at that, nobody was asking what exactly was going on in the training, so everybody assumes that training is perfect in and of itself.

Professor Chris Cushion:

Yes.

Gerard O’Dea:

That training moves the needle. And very few people are equipped to be able to look at training in the way that Chris did with my course and in the way that we do now with other people, very few people are equipped to look at training and see whether or not it has a high likelihood of producing good learning or not. And that, I think, is a real step forward. So that I think people haven’t asked the question as to whether training is effective by knowing what effective training looks like or how to create learning. And that’s so interesting-

Good Training Requires Good Instructors and Good Content

Al:

Let me see if I understand. So you’re saying that these healthcare studies, that people were going, oh, okay. Well, the training didn’t work. And in their mind, it meant the content was not good and if they could just find better content, then that training would work because you’re standing up and you’re doing whatever you’re doing in class. That part of it must be fine so it must be the content that’s the problem-

Gerard O’Dea:

Absolutely

Al:

… and what you’re saying is that, no, no, no. The content’s probably is all great, it’s how you teach that content that’s actually the problem and most people don’t understand that.

Gerard O’Dea:

Absolutely. I think Chris… Sorry to cut across Chris.

Professor Chris Cushion:

Right. No worries.

Gerard O’Dea:

He has said for years, it’s probably about the how we teach and less about the what we teach. And I’ll hand off.

Professor Chris Cushion:

I mean, it’s really interesting having traveled around with Gerard and a range of trainers in a range of industries. It’s really hard to get the… We start the conversation around how we are teaching, what’s the learning environment we’re creating, and it very quickly descends into a what we’re teaching discussion. The people want to talk about techniques, they want to talk about systems, they want to talk about this hold is effective, or this is how you deal with this person. The what we teach so without ever thinking about, well, you can have the most amazing system in the world but if you’re not creating the learning environment, if the how you teach isn’t there, then it doesn’t matter what you’re teaching to people because it isn’t going to work.

Modifying How We Teach Aids in Moving the Needle

Gerard O’Dea:

And so, we see two different responses here to the problem of making, whether it’s healthcare or law enforcement or security or whatever, making conflict management training work. What we’ve seen in the UK in recent months and even in the last year or so, is that we add to the content. If the training’s not working right now, we need to add more content. So we’re going to add elements of human rights, we’re going to add elements of equality and diversity. We’re going to add elements of understanding your own duty of care and your duty to do various things. And so, that’s one way we look at it and I think that’s wrong because if we understand that it’s how we teach can really move the needle, then the understanding has to be that if you always do what you’ve always done, then you’ll always get what you always got. And I think that’s relevant, Al, to some of the discussions you’re having in the U.S. right now about, we need to look at how our police are interacting with people on the ground out there, and how do we change that.

Al:

Yup. And it’s, I’m sure you guys see the news over there with what’s going on. It’s always, oh, lets… It’s just what you described, Gerard. It’s, oh, we need to add a de-escalation segment to our curriculum. We need to add a diversity or an implicit bias segment and that will solve the problem. But there’s zero discussion. You just never hear it about, oh, let’s go back and actually think about changing the way we train so that whatever we’re teaching them, they remember it and they apply it when they’re out in the field.

Professor Chris Cushion:

I mean, most interesting for me, Al, if we talk about the police particularly and even, and I’m sure it’s the same in the U.S. but in the UK, the officer safety training, the PST, the physical stuff, is desegregated from the verbal so that’s the first problem. But both of those things are desegregated from dealing with people so they might, a police officer or any contact professional, you walk up to a person, you have some kind of engagement with them, it isn’t segmented, it’s a, “Well I’m going to talk to you a little bit about the law now, and then I’m going to talk to you about this, and then I need to be conscious of your ethnic background or your sexual orient-” No, it doesn’t work like that. So the whole training approach really is blocks of stuff rather than, well that’s not how it works on the street. We don’t engage with people in little blocks and little segments. It all happens all at the same time. And what’s really interesting from my perspective, so as a part of the research I did specifically with police training and there’s something called the hidden curriculum.

Professor Chris Cushion:

So people presume that the what and the how is always neutral. It isn’t. Yes, we can talk about learning environments and the effects of learning, but there’s lots of implicit messages around the culture about how we deal with people of color, how we deal with women, how we speak to people we suspect of a crime, how we deal with vulnerable people. All of that is implicit within how we engage with people. And how instructors model that, how that’s delivered, how that’s taught, in the hidden curriculum in what’s really an overt curriculum, so that we could have a verbal de-escalation of physical skills program, but we’re still ultimately dealing with people and how we deal with those people will come through the explicit curriculum. So my feeling is, a lot of this stuff actually isn’t needed. We don’t need an unconscious bias segment, we don’t need additional EDI. We need to think about how those attitudes are projected and challenged in the training that we’re currently doing.

Expanding On Core Principles

Al:

Interesting. Okay, so I think we’re real clear now on, the goal of training is to ensure that year from now, two years from now, people are still actually doing what you taught them in the field and they’re getting the results that you promised them. So, that’s a big deal. I think, if I understand it right, there’s the whole task approach where people are actually doing in class what they’re ultimately going to do when they’re back on the job, and they get a lot of repetitions in and you’re embedding that in them just like you would do with driver training. So what, and we only have a few minutes left and we’ll clearly need to come back and go into more depth, but just to maybe put a few more things on the table, what are some of the other core principles then that apply to this whole task training?

Professor Chris Cushion:

Okay, well-

Professor Chris Cushion:

Yeah, I mean, I can jump in on that. So a principle is that a skill is never learned in insolation from its context. Okay, so, people need to understand not only the purpose of what they’re doing, but the product and us telling them or showing them a video isn’t enough. They have to experience it. So they have to make sense of that for themselves. So everything, every piece of skill, is connected to the context. So, we have to construct a context that we do that. And essentially the approach is to just, so yes, we need skill development, but we also need to have problem-solving and decision making. So, again, the whole task approach advances all three of those things at the same time. So traditional training would say right, bent the skills in first and then we’ll put some decision making in and then we might have something at the end where there’s a problem you have to solve. So there’s a linear end-on-end approach.

Professor Chris Cushion:

So a whole task approach from the get-go says you need to have some skill, you need to have some decision making, you need to have some problem solving, and this skill needs to be in context. You need to understand why you’re doing it and how you’re doing it. So all of those things happen at the same time. Now there’s a common misunderstanding that when people talk about a whole task or a scenario approach, they automatically zoom straight to the full-on, full max craziness, that’s all crash, bang, wallop, everything’s happening at once. And basically, a whole task is basically a complex scenario. So the most basic scenario simplified and modified and we simplify and modify it by adding rules, adding conditions, taking things away, and occluding different things.

Professor Chris Cushion:

So if you can imagine when I talk to police officers, essentially when you start speaking to a person, so when, for example, they’re in custody, so you’ve got a whole range of things, that’s a whole task. But we can start adding conditions and we can start occluding different elements of it so it simplifies it and modifies it, but you still retain the integrity of realism. You’re still going up to somebody, you’re still introducing yourself, you’re still telling them why you’re there, you’re still having some interaction, and then whatever the focus of that particular scenario or drill is, that the technical skill or element is backed in, and obviously that comes with how you’re working with different people.

Professor Chris Cushion:

But you always start and finish with the whole thing. So, when I speak to police trainers, I said basically it’s real life. You start the ebb and you get the scissors and you snip the end of that context and you snip and you bring it into the training room. And the beauty of the training room is we can slow things down, we can speed things up, we can have do-overs, we can block certain things out, we can add certain things in, so we basically start controlling and almost becoming game designers by adding or reducing pressure according to the needs of the learner essentially. So it’s a-

Trainers - Wizard of Oz Behind The Curtain

Gerard O’Dea:

One of my favorite analogies that I use for what Chris is describing there, is the trainer as a kind of Wizard of Oz behind the curtain switching levers and turning dials to create circumstances in the training that bring out the things we want the learners to learn. And that, to me, is that levers and dials kind of analogy is about how we craft the training environment then.

Al:

Well, and just listening to you guys, I mean, my brain is going back, because you brought it up early on, of driver training. And we spent a little time in the classroom learning what the basic signs look like and what the rules were, but otherwise, you were in a car and you start in the parking lot. Maybe then the guy would take you out in the highway and then you have a busy city street and, I mean, that was it. It was him, he was the Wizard of Oz behind the scenes making sure that during that in-car driving time, you got exposure to all the different things you were going to maybe end up having to experience later in your life.

The Art of Instructing

Professor Chris Cushion:

Yeah. Absolutely. And I think, in many ways, this asks different questions of the instructor and the trainer. There’s a real art or, this is where the skillful practitioner as a trainer comes in. You’re not just delivering a set of blocks that you can do in your sleep basically, that everyone just does reps, move on to the next block, everyone does reps, move on to the next block, everyone does reps. This is great. I’m doing a great job. Now as a trainer, you really need to be in tune with what’s happening in front of you, in tune with the learners, to dial things up, modify, reduce the demands, increase the demands, put different air in playing, exaggeration, and more emphasis on different areas of it, and actually coach and work with the learner through the design of the practice, but also supporting not everyone will experience things in different ways.

Professor Chris Cushion:

And I think, you don’t throw the baby out with the bath water. You still need confidence and competence and that’s where blocked practice comes in. So it may be, for example, that you’re working through a task or a whole task and there comes a point where the learners are maybe struggling with a particular technique or you need to emphasize that. For me, I would then put block practice in and said, okay, so it might be using mechanical restraint or handcuffs and we’re not really doing that very well, let’s just do some reps putting handcuffs on. Let’s rep it over and over again. And then back it back into the scenario and then try it.

Professor Chris Cushion:

So, these things serve a purpose. If people aren’t feeling confident using a range of different handcuffing techniques. If people aren’t feeling confident, well, how do we give them confidence? We let them block practice it. They get more confident and then they apply it back into the scenario.

Al:

And you mentioned that to me when I was in there in the UK in December and it really hit home with me that the difference, and maybe this is just me thinking about it wrong. But one side is, let’s do the drill practice, the block practice, first, and then let’s go apply it. And you’re saying, no, let’s do the application first, the real scenario, the whole task, and then during the whole task, you’re going to discover the things that people need blocked practice on and they’re going to ultimately ask-

Professor Chris Cushion:

Correct.

Al:

… to be trained on that further because they’re uncomfortable with it. And then, it seems like the learning experience is so much different then because they know then where in the whole task this applies and then you go, okay, now let’s go back and learn how to handcuff.

Professor Chris Cushion:

Well, they understand the purpose and they understand the product. So it’s not somebody telling them. They understand where it needs to happen and why it needs to happen, first of all. But it’s also, when people have ownership, as soon as they’re attuned into the best place for an instructor or a coach is when someone’s asking you for feedback, asking you, not the other way around. That means that their attention and their focus on learning are incredibly high and they’ve taken ownership of it. So I need you to tell me this. I need you to show me this because I understand where it fits. And suddenly, there’s no doubt then that, this is no longer isolated from context. They totally understand where it fits

Al:

Exactly.

Importance of Context

Gerard O’Dea:

Can I jump in there, just talking about context and it’s importance for a moment. When I first went to do the work, for example, that really key secure escort training course that Chris and I collaborated on. What I found was that the previous training provider there had a five-day course that they were delivering. There were something like 85 different physical techniques listed for the learners to learn. The entire task focuses on getting people onto a vehicle safely and then getting them back off the vehicle safely at the other end, with a couple of handovers at either side. And yet on the training course that we were replacing, four and a half days of the training was done in a gym with nothing to do with a vehicle. And so, everything was decontextualized in regards to where those skills would be used and how they needed to be applied, for example, inside a small vehicle.

Gerard O’Dea:

And so, just to add the legal points on that, several coroner’s courts here in the UK which deal with sudden deaths and unexpected deaths and so on in custody, have looked at the problem of decontextualized training, for example, with Jimmy Mubanga which some listeners to this podcast will understand. He was an immigration deportee who died on a British Airways flight several years ago. The coroner specifically pointed to the fact that that team had never been trained properly to use their tactics in an aircraft environment.

Al:

Oh, wow.

Gerard O’Dea:

And so, part of what really rings true from what Chris is saying here is that he’s saying that we need to make sure that the trainees contextualize to the real-life workplaces in which the tactics will be used. And we’ve taken that and really run with it at Dynamis because we, just today I was teaching people who meet members of the public out in public spaces. And so we start our training design from looking at what are the issues there. So it doesn’t always have to be about a fancy confined space or a particular vehicle or piece of equipment.

Gerard O’Dea:

But making sure the trainees contextualize is really important. And my last point on that is that meeting an expert witness here in the UK who is very well-respected, Eric Baskind, back in January I think it was, just before lockdown, and one part of his masterclass presentation was that something that’s been termed the choreographed dance of training, which is this blocked practice, heavily supervised where everybody gets it right very quickly and we move on, is that choreographed dance of training is dead because the judiciary, the people looking at these incidents now realize the training has to be effective in producing real-life learning. And that’s one of the reasons I’m so interested in it is because we have people looking at the effectiveness of the learning as one of the key points in what might be affecting the key metric in our sector which is fatalities during restraints and use of force instances.

Al:

Yup. Just, one other point that you guys have both shared with me is that everybody comes to class with some background and experience in what you’re teaching them. Nobody’s coming in with a blank slate where they’ve never had any conflict, they’ve never been punched, they’ve never been hit, they’re coming with something and this whole task approach seems like it gives you the opportunity to learn what they know and then say, well, you already know this stuff. Let’s focus on the stuff you don’t know. Is that a valid point?

Professor Chris Cushion:

Absolutely. And I think an important guiding principles of the coach or the instructor is that you modify the situation to the level of the learner. So, that will depend on their previous experience, their previous knowledge. So you can, in the same teaching space, you may have the same task running, but you might tweak it or adjust it according to people’s past experiences and are those experiences appropriate. Basically, you can treat, you can individualize the learning within this really and you can have a differentiated way of working with people. So, again, I’ve worked with some very able police officers who are very well trained and arguably probably enjoy the physical contact and I’ve worked with some police officers who couldn’t fight themselves out of a paper bag. So they’re in the same session at the same time having to learn the same things. So you have to set up the task and challenge them and modify the situation to the level of the learner, and then progress them forwards, their skill level and their understanding, and [crosstalk 00:47:39].

Al:

But you’re going to know that, right? And, Gerard, I know that you get people up really quickly. They’re doing some whole task stuff within the first hour versus that other example you used in the last half-day of a four-day or five-day program. And with that other company, that guy had no idea what skills they had until the last half-day of the program.

Gerard O’Dea:

Correct.

Al:

You find out where they’re at in the first two hours.

Gerard O’Dea:

That’s right and I think that other approach where you save the scenarios, so to speak, until the last day of a several-day training program, is a really big ask for the trainees, the learners, to glue all of those components together. Imagine being on a course where you learn 85 separate and distinct tactics and then on the final day of the course somebody says, “Hey, in a rapidly unfolding tense, uncertain situation, I want you to glue these together appropriately and it’s pass-fail.”

Al:

Right. Yup.

Gerard O’Dea:

So that’s unfair and it’s not good for learning so it’s not getting what we need from the training either. It’s probably creating, in its own way, and just talking again, referring back to Chris’s idea of the hidden curriculum, pass-fail is maybe not how the real world works. If we’re trying to establish a culture of failure and a culture of taking feedback and moving forward with it, maybe those types of tests aren’t what we should be doing with our learners.

Professor Chris Cushion:

But I think they’re really-

Gerard O’Dea:

And-

Al:

Go ahead, Gerard.

The Problem With Pass-Fail Training

Professor Chris Cushion:

Just on that really, it’s really interesting to watch. In that type of training where there is a pass-fail and you’re being tested, very often the instructor will call out what you have to do. So they’ll call out, this is happening, I want you to demonstrate this technique, so there’s no thinking. And what I’ve done to be mischievous in the past is, I’ve just said, do something. I’ve not picked one of the 85 things. I’ve said, okay, well something’s going to happen and you need to do something. And what’s really interesting is people who previously were very skillful at the individual techniques and were, if you’d watch them, you’re going, “Okay, this person’s fine.” But as soon as you don’t give them a clue or you don’t direct them, you say, “Well, I just want you to do something,” it’s like a rabbit in the headlights. It’s really, really painful actually to watch and think, okay, these people haven’t learned anything and they’re not trained, is what I’m seeing.

Al:

Exactly. Well, and Gerard, I know a few weeks you dealt with that care facility in Scotland and I think you discovered early on that they had some really, really strong skills in some areas and they needed, because you had them up doing stuff right away, and you knew that so you could kind of put that aside and say, okay, they’ve learned that somewhere in their past and I don’t have to worry about that. We can certainly repeat it during the week. But in know they got that, and then able to focus your attention and time on the stuff that was new to them and they didn’t know.

Gerard O’Dea:

Yeah, it is about having that open mind and looking at your learner and saying, right, what are these guys doing well already. And then I can, as appropriate, focus on the things that they need to develop. One of my bugbears again, looking at training programs is where the instructor will get a group of people into a room and say, for the first two hours this morning we’re working on stances. And the fact of the matter is, everybody walked into that room using both, whatever way they did, they managed to move around in the room appropriately to the context and they don’t need this separation of skills. And then we have people who’ve been doing conflict management for example, deescalating people in crisis for years and we need to be able to look at our content, our what to teach, and match that to what people are actually doing in front of us, that recognition of their skills rather than being so curriculum-focused and content-focused that we ignore all of the things that people bring into the training room.

Al:

Well, and sometimes, and you’ve given me examples of this, where all you’re really doing is, they’re doing this exactly according to the curriculum. They already know how to do it and you’re giving it a name, right? And now they have a name to associate with it and some confidence that whatever they were doing, and they’re doing it right.

Gerard O’Dea:

Absolutely.

Al:

And that by itself is a big deal, right?

Gerard O’Dea:

Yeah. Absolutely. I had that group up in Scotland recently who they walked out of the room after four days and said, “You know what, we did this so often, I’m not sure I could get it wrong now.” And secondly, they said, “What’s even better is, I can now explain it to somebody else because before I was just winging it. And I was winging it pretty well based on my experience. But now I’m conscious of what I’m doing, I can give it a name, and I can explain it to somebody else.” We hear people talk about conscious competence. And you get that from recognizing people’s prior experiences in learning and then working with it instead of trying to replace it somehow with whatever training program is your content.

Conclusion

Al:

And I guess we could keep chatting for a long time. I’m extraordinarily curious about this and eager to learn more, but we’re a little bit even past what we thought we were going to do, so let’s end it there, and let’s plan to get back together at some point and dig it deeper. But I big-time appreciate your time today. I hope everything in the UK is well. As you know, we’re, well I don’t know when this will actually get launched, but we’re in the middle of our every four-year presidential election so it’s creating a little bit of angst, along with our pandemic, which I’m sure you guys are dealing with. So a lot of stuff to deal with. I don’t think there’s going to be any shortage of conflict in the near future.

Gerard O’Dea:

Absolutely. Yeah. Very true.

Professor Chris Cushion:

Absolutely.

Al:

Thanks so much.

Professor Chris Cushion:

It’s a pleasure.

Gerard O’Dea:

It’s a pleasure

..