“Mental Health Training’s Role In Law Enforcement ” - Episode 4

Host: Al Oeschlaeger

Guest: Jeff Campbell

Subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher, Google Play or YouTube.

Jeff Campbell, Captain with the Eaton County Sheriff’s Office in Lansing, MI, joins us to chat about the positive impact on his law enforcement team by their use of Crisis Intervention Training coupled with Vistelar’s verbal de-escalation techniques. Campbell shares specific instances where an officer’s training in mental health awareness helped lead a situation to a positive outcome. Can this training also effect the public’s view of law enforcement’s role in their community?

Allen Oelschlaeger: So welcome to another episode of the confidence in conflict podcast. Your destination to learn how to better manage conflict in your personal life and your professional life. I’m here with Jeff. Welcome Jeff.

Jeff Campbell: Hi Allen, how are you?

Allen: I’m good. We’ve been trying to get this scheduled for a while, so I’m glad to have you on the call.

Allen: Maybe for the audience, just give a little summary of your background and how you know us here at Vistelar and whatever.

Jeff's Background

Jeff: I currently work for a Sheriff’s office in the Lansing, Michigan area. I’ve been with this agency for just a little over 24 years and my background is 25 years in law enforcement with lateral patrol and investigative experience. Back in 2014 I became an instructor for Vistelar through Dave Young.

Allen: Oh wow. I didn’t know it was that far back, so that’s great. Okay, so about five years.

Jeff: Yeah. Getting pretty close to five years now and we’ve been running this program, teaching this program at my agency ever since.

Allen: How many folks in the department there?

Jeff: We have about 70 sworn road control on the law enforcement side and above another 35 corrections personnel.

Allen: All those people who have gone through the Vistelar or training program in some form?

Jeff: Correct. Everybody that gets hired here now goes through that as part of their administrative training in their first couple of weeks working here. They have a baseline for it and then they continue on with their field training.

Allen: Very cool. Then you also have, you’ve been actively involved in the CIT or crisis intervention training in your area?

Jeff: Yes. For about the last three years.

Allen: Oh, okay. Tell me more about that. I know you know we have a CIT here in the Milwaukee area. Actually one of our trainers, Joel Lashley presented at the CIT program that was out in Waukesha, which is a suburb here of Milwaukee. They run these programs differently all over the country. Tell me more about how this works in Lansing.

Jeff: We put ours together as a cooperative effort and what we call it is the Tri County crisis intervention team. It’s a collection of agencies, police agencies from the Ingham Eaton Clinton area of Michigan, mid Michigan area. As well as hospitals in our area and mental health facilities and counselors, therapists, doctors from various disciplines. We all come together and that came together about three years ago or so designed the curriculum based on the national CIT model.

Allen: Do you have a NAMI office there?

Jeff: We do. Now being Lansing with representatives on our CIT board. We are a fiber one C3 board now, just recently established as a board. We can manage the funds that we need to keep the train going and so forth.

Allen: Is the NAMI there, I know here there’s actually paid folks, is it a volunteer group or is it…?

Jeff: Ours is a volunteer group?

Allen: All the NAMI people are volunteer too?

Jeff: In my particular area. Yes.

Allen: Just for the folks that don’t know, so NAMI, I know that’s what? National Association of Mental Illness.

Jeff: I believe, National Alliance for Mental Illness.

Allen: I think so, yeah.

Jeff: Put me on the spot there, yeah.

Allen: Did they start in Memphis or is that somehow…?

Jeff: No. CIT originally started in Memphis, Tennessee. Major Sam Cochran I believe, is one of the founding members of the CIT movement but it started in Tennessee years ago after a fairly controversial shooting of a mentally ill man.

Allen: Then how did NAMI get… Do you know how they got involved in…?

Jeff: I think they see, at least from speaking to our local volunteers, they see it as a necessary connection between people who are suffering from mental illness and law enforcement, because there’s so much interaction between the two. They see it as a really important… tactic or piece of training for law enforcement and how they can better deal with mentally ill and seeing it from perspective of people that have gone through that.

Allen: Do you know how many… At some point it sounds like NAMI just adopted the Memphis CIT model and said we’re going

Jeff: Yeah, they definitely support it. Pretty strong.

Crisis Intervention Team (CIT)

Allen: I think it varies by the area, but you said that in your area it’s a 40 hour program. Just describe it for the group here is, what do you do during those? It’s for law enforcement, right? CIT. It’s a law enforcement program.

Jeff: Yeah. Law enforcement and corrections in our area.

Allen: And it’s a 40 hour program.

Jeff: 40 hour

Allen: What do you do during the week?

Jeff: It starts out with an introduction to verbal non escalation, de-escalation tactics. We go through a very, very short version of the Vistelar program or something similar to it. That’s basically just an introduction. We also spend part of the week introducing them to the various different mental health diagnosis possibilities, the medications that people use. We talk a lot about substance use disorders, those kinds of things. We bring in doctors and therapists, experts in particular aspects of mental health to talk about each of those things. It ranges from, like I said, substance use disorders to elderly people with cognitive disorders or dementia and everything in between. We give them a basic familiarity with all of those things and we take the verbal tactics and the knowledge of those things and we do scenarios and so we actually put them through a number of scenarios along the way throughout the week.

Allen: Oh cool.

Jeff: They get a chance to practice the verbal tactics in a situation that they’ve been taught about. It could be dealing with a homeless person with some sort of mental illness for one scenario and then they might go to a youth situation with a completely different diagnosis.

Allen: Are the speakers… How often do you do the class?

Jeff: Twice a year. We’ve been doing it twice a year and I think we’ve done a total of five classes now. We’re going to be doing our sixth one here in December.

Allen: How many people would be in a class?

Jeff: We take a maximum of 40 per class and we filled up every class so far, so yeah.

Allen: Wow. The speakers that you have… Because I know that here in Waukesha, I think there was, over the course of the week, I looked at the agenda, I was only there for a day, but it seemed like there was maybe eight or so speakers. How many folks do you have involved?

Jeff: Probably more than that. The thing that I think is unique about our program and maybe it’s not as unique anymore, but for one I hear we’re one of the only places doing it this way. We use all volunteers from our local area, or local expertise, or local backers come in and they speak and they obviously aren’t charging us anything to do this. We have a pretty wide base of people that are committed to doing this and making this training as inexpensive as possible. We’re charging $100 per officer for this training and that’s basically just enough to cover our materials and we bring in lunch for the class so that we can basically work through lunch.

Allen: So, how many speakers would you have?

Jeff: Oh, probably 15 depending on the block and training. Sometimes we have a panel of speakers that will come on and tag team a particular type of block of training. No outside funding whatsoever. No grant funding, no consultants. From what I hear that’s pretty…

Allen: You’re just using a space there at somebody’s…?

Jeff: Yeah, the Lansing police department hosts it and they’ve got a really good area for spreading out to do scenarios and the training

Allen: So, you’ve had five classes, is it basically the same 15 people each time, or is it a whole bunch of different people each time?

Jeff: For the most part, the speakers and the instructors are the same. We sometimes we’ll have to switch it out. One doctor might not be available at this time so we look for the backup. It depends on the situation. Yeah.

Allen: So there’s psychologists coming, psychiatrists, people that know about, like you said, drug abuse, cognitive disabilities, dementia, and it’s local experts in all those areas and they come in and they do like what? An hour kind of segment, a couple hour segment?

Jeff: Yeah. It depends on the segment. Most of them are at minimum, a half hour. Most of them are an hour or so. We also covered the legalities, the mental health law in Michigan and go over that with officers in the course.

Allen: Is it all in the classroom or do you go out and do any visitation?

Jeff: We do not do any visitation anywhere. It’s all in the classroom or in the building where we set up the scenarios.

Goals of Mental Health/CIT Training

Allen: Yeah. I know this Waukesha group, I got the impression it was maybe a day of the five days they went out and visited a local, I think nursing home, maybe a mental health institution, mental health clinic, just to see kind of firsthand what some of this is like, maybe a homeless shelter. I’m not sure exactly all the places they go, but you’re pretty much in the classroom. How would you describe the… What’s the primary or top two or three goals here for the training? What are you trying to accomplish by the end of the week?

Jeff: Number one, to introduce verbal tactics that a lot of the officers that are in this class are pretty familiar with it anyway, or pretty much practice this in the course of their normal duties, even though they may not call it the same thing that you and I would, but they’re kind of already doing it. We give it a name and we go through some tools and tactics that they can use. For the most part they’re already pretty good at it. So now we just take it and we specifically focus on people in crisis, whether it’s due to a mental illness or substance use, we give them some tools that maybe they weren’t previously aware of for handling those situations. We give them some familiarity on the various mental health diagnosis out there and what they might be able to do to recognize that or respond to it, even if they don’t necessarily recognize exactly what it is.

Allen: Yep. So, that was my impression and what I saw a couple of weeks ago. It’s a mix. Tell me what percent. Obviously part of this is just an awareness of and knowledge about what’s mental illness like? What are the different attributes? How would you identify it? Substance abuse, all the stuff you described. What percentage of the week is that? I’d call it awareness and understanding.

Jeff: Probably at least half of it.

Allen: Half, yeah. Then the other half is on some tactics, and then practice, and scenarios.

Jeff: We devote a full day and a half over the course of the week to scenarios that they actually get to use the knowledge in the training that they’ve been given over the course of the week. That’s a full day and a half of the class and prior to that we’ll do maybe a couple of mini scenarios where they just get to practice or role play. That kind of thing.

Allen: What kind of feedback do you get? You’re obviously heavily involved in it and you’ve been doing this for five of them. If you were to summarize what you hear from the officers after they’re done, what do they say?

Jeff: It’s really been positive feedback, not just after the class. You’ll get a lot of people, we always stay and chat with people at the end of the class and it’s nice to hear what they think is most important. It’s different for everybody, what they get from the class and what’s most stands out the most to them, but what I really like is, weeks and months down the road you start hearing stories about how you use this or something that they’ve learned in the class, help them handle their particular scenario. I hear that probably most often from the people in my own agency, but I’ll run across people that have gone through the class at other agencies and it’s fun to talk to them about it because you see how beneficial it can be.

Allen: Big time. Let’s talk through an example so the listener here can figure out what we’re talking about. So you’re a law enforcement officer. You’re dealing with, obviously it’s in the news like almost every night, some kind of mental illness issue. Obviously, those can go South. Tell a story or whatever about what this is like and what tactics maybe people learned and either, CIT, but then also the Vistelar training, whatever that would apply and how they make a difference.

Effective Crisis Intervention Strategies

Jeff: I have one that I think is a really good story and it was shortly after we went through the crisis intervention training. I have a deputy that is actually a veteran of the Marine Corp and served some time in combat in Iraq. He’d been with us for a while and went through the crisis intervention training. Not too long after that we were called to assist one of our other local agencies with a person that was having some sort of crisis due to mental health and alcohol use, that kind of combination. When he got there, he had already been smashing bottles and walking through it with bare feet. He almost completely undressed and was out running around in a fairly large backyard in a residential area and was gathering a crowd in the neighborhood, obviously. He was shooting down or trying to shoot down the helicopters that were flying overhead that he thought he was seeing.

Jeff: Obviously a number of cops showed up. This deputy who was kind of giving the lead on it, because he has the military background, he’s a CMT officer, so he kind of took it over and it was probably roughly 30 minutes or so of just working through number one, getting to get his attention and keep him focused on something other than the helicopters and the crowd that that were distracting him, just to get them to talk to him enough to be able to start to calm him down a little bit. It’s a really cool thing to watch. There’s some really good video of it too and it takes away the enormous amount of patience.

Jeff: You can see that it took a lot of patience for that particular deputy, but also the other officers involved because he’s mobile, he’s moving around, he’s got a pretty wide area to move around in, and we’ve got number of officers there that have to basically just try to keep him somewhat contained without provoking anything or escalating the situation by their body language, or their mannerisms, or words and they all did just a great job of kind of stepping back and letting him have the lead role and getting him to focus on one particular person and talk through that. As he does it, you can see he starts to calm down a little bit and he finally sits down and they start talking. He eventually is able to get him to into handcuffs without any force whatsoever. Got him to the hospital shortly after that so…

Allen: Jeff, I’m going to interrupt, just so people don’t miss it. This was 30 minutes, right? When you talk about patience, you were listening, and stepping back, and slowing down for 30 minutes before he got to that point. Is that right?

Jeff: Yeah, and it went up and it went down. He’d start to get some ground and it’s like a two steps forward, one step back. He’d started to gain some ground and get him calm down and then the guy would spot somebody in the neighborhood and that would make him mad. So, he had to redirect it. Get him to focus his attention back on the deputy, and talk to me. It helped that he had the military background because they could talk about some similarities in their experience. That was definitely a huge factor in this particular situation I think because he could talk the talk. He had some real world experience that he could talk about. That he can relate to this guy with. That definitely made a huge impact I think.

Allen: It’s like a huge point, right? In most law enforcement, that’s not the normal natural behavior to just kind of hang out for 30 minutes, right? You’re in there trying to take action, and get something done, and get the handcuffs on. [crosstalk 00:19:38] This a different mode of operation. You’ve got to have some patience.

Jeff: It’s becoming a lot more than norm in law enforcement than maybe it was 25 years ago when I started. It’s moved towards a lot more of a time, distance approach. Taking your time, you maintain the appropriate distance, and you make good use of your cover. You at least know where it’s at. That’s what we’re teaching our people. So, you’re seeing a lot more, I think in law enforcement in general, but at least around here you’re seeing a lot more of that situation overall.

Allen: Maybe, more to say it’s not human nature, maybe is the better way to state, right? You got a problem and you want to go fix it rather than…

Jeff: It still amazes me how people in general, who aren’t in law enforcement want us to move a lot faster in a situation like this then we’re going to do and they don’t understand why we’re not just running in and grabbing the guy, throwing them on the ground, and put them in handcuffs and haul him away.

Allen: Exactly. That’s more my point.

Jeff: That still surprises me sometimes where we get crucified over the way we handle something when we go too fast, but then when you’ve got a crowd out there, they don’t ever think you’re going fast enough.

Allen: Yeah. You know Joel Lashley, one of our trainers, but I think… I don’t know if I got this exactly right, but he says, there’s a tendency to talk too loud, get too close, talk too much.

Jeff: Yeah, exactly.

Allen: You just got to slow down… Just describe, during that 30 minutes, you said at the beginning here you said, during the CIT training and the Vistelar training obviously also, you’re learning some de-escalation and crisis intervention tactics. So beyond just being patient, and slowing down, and being willing to take your time, and not rush things. Give me just a couple of examples of what would happen during that 30 minutes.

Jeff: One of the things that struck me about it, and maybe this isn’t textbook, but what I thought the deputy did really well was being able to read exactly how he needed to project his voice at any given moment. He would start out with sort of like a drill sergeant voice, because he needed to get that guy’s attention. He’d get that guy’s attention and the guy would respond to it, because he’s a military guy. He knew exactly how to say it in that right way. Then as soon as he got the attention, the deputy ramps it right down. I was talking to him in a little bit more of a soothing voice and you know, Hey, this is how I need to talk, this is how we’re going to talk to each other and if he’d lose him again, he’d go right back to drill sergeant mode. Just for a second until he got his attention.

Allen: Just to get his attention. I love it.

Jeff: It works really really well. That’s something that, I don’t know if you can teach somebody that necessarily. This particular deputy is just really, really good at that. [crosstalk 00:22:56] to be able to read that situation.

Allen: Yeah. Jeff, and as you know, we teach it and I’m sure it’s part of the CIT is that when you’re interacting with somebody, obviously, your words matter, but that tone of voice matters way more and your positioning relative to the person. I’m sure you know, this guy wasn’t in the guy’s face. He was back, whatever, some period of some distance.

Jeff: This was a credibly 40, 50 feet here at least, at various times and they didn’t really get close to each other until right near the end where the guy finally agrees to comply and allow himself to be handcuffed.

Allen: Again, to reemphasize that, you’re 40 feet away in this interaction. You’re not five feet or three feet or where you might normally think you’d be, you’re hanging back and tone of voice, crazy important. Obviously words being important, but tone of voice being more important. We call that proxemics of just how your whole body positioning relative to that other person and your tone of voice. All that stuff’s got really, really important. So, you got that. So the guys, great tone of voice, he’s dealing with the guys Marine background and then bringing the person down by the tone of voice. Right? If you’re loud, they’re going to rise up to where you are. If you’re quiet, they’re going to… hope come down to where you are. Right?

Jeff: As you can imagine, there’s quite a few verbal assaults going on from this guy. What I really also liked, not just the deputy that’s doing the main interaction with them, but there’s other cops out there and he’s insulting them one by one, saying various things to them, trying to get them to engage with him and they’re not. They’re basically redirecting him right back to the original deputy, the main deputy who’s got the lead on this. That helped keep him from escalating. It could have been very easy for any of them to think, well, he’s not getting anywhere I’m going to take over, but they didn’t do that.

Allen: Two things here. Just expand a bit on, obviously it’s a term you and I know, is redirection. Just for the listeners tell us what that means.

Jeff: It’s like a springboard, basically where you’re deflecting the verbal assault and you’re redirecting them back to the task at hand I like to call it, or the issue at hand. If somebody calls you fat and bald, like in fairness, one of the things that this guy said, to one of our officers, it was you’re *******. I hear ya, but you’re not talking to him, you have to talk to me. Okay. He’s just there to make sure I stay safe. Let’s talk to me. Okay. So he would just keep him focused on one particular person. You can see when he finally realized that nobody else was really going to talk to him, if he wanted to keep talking, engaging with anybody, it was going to be that one particular person.

Allen: Let me jump on that just for a minute and then we’ll come back to redirection, because one voice is like crazy important in these situations. That the guy hearing… Obviously there’s things going on there and we got Joe over here saying one thing, and Bill saying something else, and Mary saying something else. His brain’s not working perfectly. It’s really, really tough, right? For that communication to occur. You get one person, right? And everybody else is being quiet. That’s a big part of that.

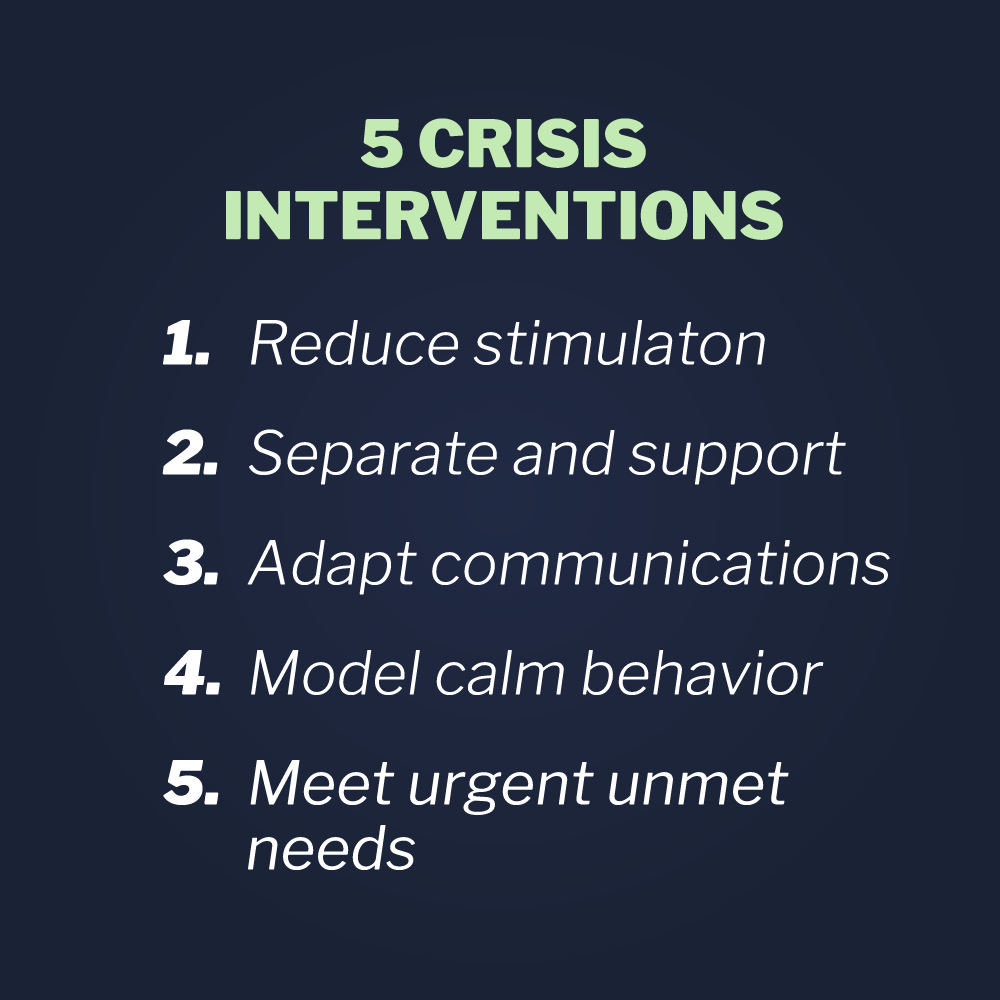

Jeff: Yeah. You can easily overwhelm somebody in crisis with yelling or loud voices or too many people moving around too quickly, too much light. Too loud of sounds in the background. It’s so many things that can keep you from communicating with a person in crisis that you’ve got to try to manage some of those.

around too quickly, too much light. Too loud of sounds in the background. It’s so many things that can keep you from communicating with a person in crisis that you’ve got to try to manage some of those.

Allen: Joel’s five strategies, we don’t have time to go over them all here, but that’s obviously, to reduce stimulation and then adapt your communication to the situation or a couple of them and we just talked through that. Back to the redirection, the term we use is acknowledged and then back to the issue. Right? So you’re acknowledging the fact that you’re listening to the guy. It’s not that you’re ignoring him or being disrespectful. You’re acknowledging the fact that, yeah, I hear you. I appreciate that. You called me bald, I hear you. You might joke about it. I don’t know if it would’ve worked with this guy, but then let’s get back to the issue. You’re really talking to whoever this deputy is and he’s the…

Jeff: It was more of, he’s there just to make sure I’m safe. Yeah. He may be fat and bald, but that’s okay. He’s here to make sure that I’m safe. I want to talk to you about what’s going on with you. What’s happening that makes you think that we aren’t here to help you, that we’re going to take you to jail. Because the guy was concerned that he was just going to jail for some reason. He had not actually committed a crime of any kind at that point. Hadn’t assaulted anyone, hadn’t talked about assaulting anybody. He was a threat to himself. Obviously he was disturbing the neighborhood, but…

Allen: How about how big a crowd was it?

Jeff: Not bad. It’s a pretty wide open, somewhat rural subdivision type area. You had five or six houses within visible distance of where the guy was at. Otherwise it was a fairly wide open area. The houses up real close together.

Allen: Yes. So obviously that wasn’t the problem, but that’s one of the things we emphasize a lot, is that if you’re, let’s say you were in a classroom in this situation is one of the first things you’d probably do is say either everybody in class go out in the hallway so now you’re, we call it separate in support, but you’ve separated that person from all that hubbub of the crowd. People are harder to deal with, whatever their feelings are about people watching and whatever. You’re getting rid of that or if the opportunity exists, you go out in the hallway with that person and everybody else stays in the classroom.

Jeff: Yeah. In this particular situation we were not going to be able to do that. These were people on their own property at their own house.

Allen: Right.

Jeff: That’s a pretty wide area to deal with and so obviously we couldn’t move

them away from the situation easily. The whole focus of the conversation with him was to try to get him removed from that situation. We had to work extra hard on the separating support aspect of this one.

Allen: I’m assuming, that maybe different words are used or whatever, but the Vistelar training is kind of incorporated into what you do there in Lansing?

Jeff: Yeah. Essentially it’s about a two and a half, three hour block to start the class. It’s the introduction to the overall class and then we kind of interweave the rest of it through the rest of the 40 hour class in the scenarios. We take opportunities throughout after certain blocks to go, okay, what’s a good tactic for this particular situation. Then what’s one way to handle this? And we talked before we actually go on to the scenarios.

Allen: I’m no expert in what is happening with CIT around the country, but I think in some areas it’s rather than having a base of content, like you have, you might end up with two or three different speakers coming in with two or three different ways that they’ve learned personally to de-escalate a situation. My guess is that creates a little confusion by the end of the week, with different ideas. It sounds like you guys have kind of, you’ve got some base content and that stays consistent throughout the week.

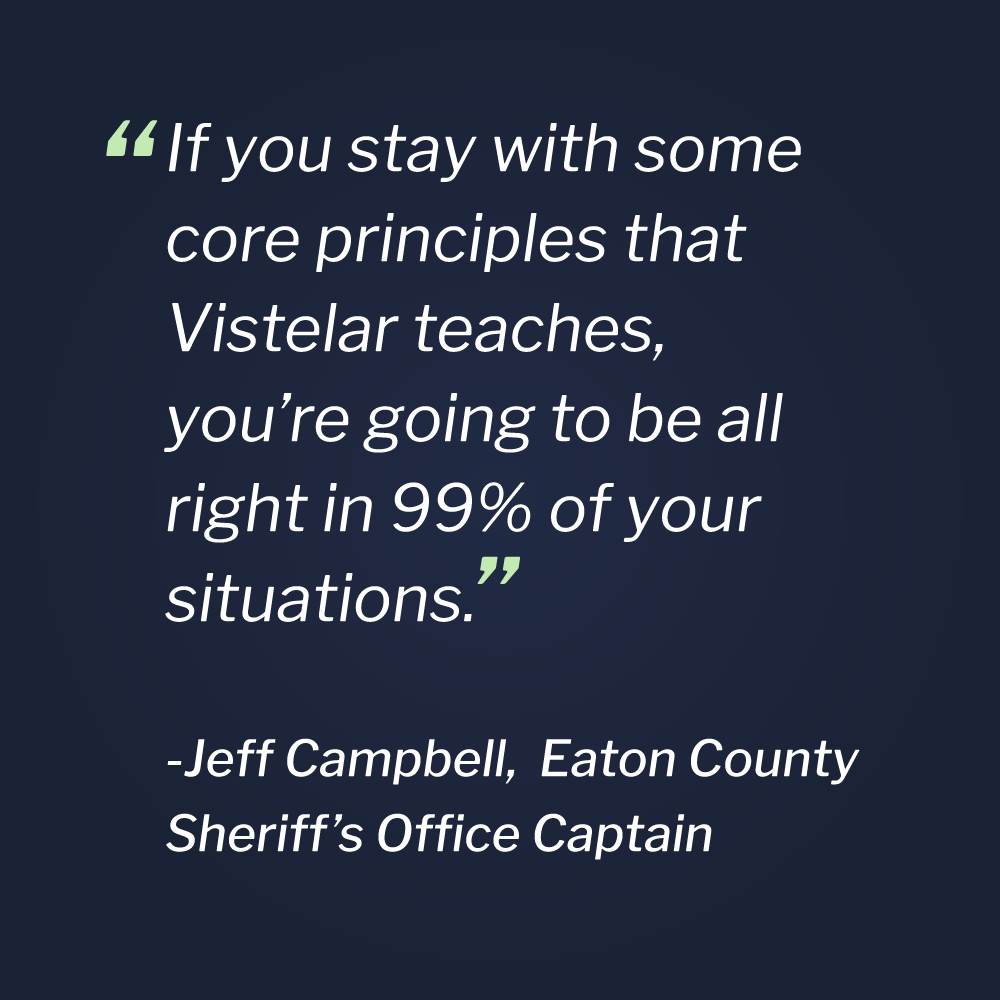

Jeff: Yeah, it generally does. Don’t get me wrong, the experts in the various disciplines that we bring in will offer up their own tips from your own experience and things that work for them. I’ve found that they often sound like a tactic that we teach anyway. If you stay with some core principles that Vistelar teaches, you’re going to be all right in 99% of your situations, regardless of the particular diagnosis that the person that you’re dealing with or because of their particular crisis.

up their own tips from your own experience and things that work for them. I’ve found that they often sound like a tactic that we teach anyway. If you stay with some core principles that Vistelar teaches, you’re going to be all right in 99% of your situations, regardless of the particular diagnosis that the person that you’re dealing with or because of their particular crisis.

Allen: Jeff, do you have any idea? I just don’t know what percentage… You have any idea what percentage of police officers in the country had been through some kind of CIT program?

Jeff: I don’t know across the country. I know in our area we’re striving to maintain about a 25 to 30% rate of our patrol force. So we’re certainly not sending everybody through it. We tried to pick the 25 to 30%, that number one want to do it, and number two, we think would be somewhat good at it. So we asked the chiefs in our area.

Allen: I see. That makes a whole bunch of sense. I don’t know if you saw it. There was an article that was in the journal Sentinel here in Milwaukee, but it was, I don’t know, seemed like the study was from somewhere else. There was somebody did some big study showing that that is kind of the sweet spot. If you can get 15 to 30% of your police department through this program and that it actually can be a problem if it’s 100%. There was actually some negative results from training everybody. I don’t know why that would be.

Jeff: Yeah. I remember that article. It’s been awhile since I read it I think the national model for CIT recommends roughly 25% if I’m not mistaken. I think they do that for, for a reason. Like I said, not everybody really wants to do this or even has the real ability to speak effective in somebody in crisis, the patience that it

takes some times.

Allen: In Lansing, is it kind of known who is trained and then they’re the responders to these situations? Is that what happens?

Jeff: Yeah, we tried to have enough, the 25 to 30% for us kind of comes from the way our shifts run. If we have 25% we’ll be able to generally expect to have one or two people working every shift that are CIT trained. If they’re available, then we try to put them as the lead for a mental crisis, substance use crisis call. So our CIT officers in this area, once they graduate from the class, they’re given a pin and it identifies them as a CIT officer.

Allen: Okay. Then dispatch and whoever would know who those people are and they would get picked?

Jeff: Yeah. We have a mutual aid agreement with all the agencies in the tri county area so if they need a CIT officer and they don’t have one working, they can call us and we’ll send ours wherever they need to go.

Allen: I love it, Jeff. From what little I know you, it seems like you got a heck of a program there and it’s volunteer and so obviously some passion to make this happen and you have people that otherwise are busy in their life coming in and volunteering their time. That’s pretty cool.

Jeff: Nobody gets any extra money for it. We just get paid through our regular jobs to teach the program, but it’s been done with very, very little funding compared to most of the other programs that I’ve heard of at least going on around the country.

Allen: I know that some are volunteers, from what I learned last week, I think some are volunteers, some are paid in terms of the local NAMI office. I think the police department sometimes is grant funded. Sometimes it’s per officer like you’re describing. I don’t know what the average per officer price is.

Jeff: I don’t know what other places are charging. When we came up with the a hundred dollars per officer figure, we wanted to build up some funds just to maintain, in case we have some extra training for instructors to send them too. Like I said, cover relevant materials, course materials.

Allen: The course materials are yours, right? You develop those internally.

Jeff: Yeah. Each of our speakers or instructors brings in their own presentation and then we collect those and we give the students a binder basically, that contains all the presentations and gives them a chance to take notes and reflect back.

Conclusion

Allen: Cool. Well Jeff, this is great. I learned a lot. This has always been… Like I said, I went to this class that Joel Ashley, one of our trainers, like you described 15 speakers. He was one of eight, he’s been in a security actually within healthcare for years, but developed if you know, quite an expertise on how to deal with cognitive disabilities. He has Vistelar, our crisis intervention stuff is partially based on what he’s learned over the last 30 years. So he’s quite an expert in quite one of the more popular NAMI speakers here locally.

Jeff: He’s definitely an expert in the field for sure. I don’t know too many guys that know more about that kind of thing than he does.

Allen: Yep. As you know, he wrote one of our books. Confidence in Conflict for Health Care Professionals and some very large organizations have adopted that. Yeah, he’s a smart guy. So anyway, Jeff this is great. I appreciate you taking the time today. I hope we’ll have a chance to talk more about what you’re doing there in Lansing.

Jeff: All right. Anytime.

Allen: Yeah. Any closing comments about what we’ve talked about here or what your thoughts about this whole issue of dealing with crisis?

Jeff: I think it’s a really bad problem that we’re facing in law enforcement. The mental health crisis just does not seem to be getting any better. And it’s something that is going to be facing law enforcement for a long time. I think the CIT model and training is going to be of critical importance for agencies to adapt and practice for the future. So, until we can figure out another way to tackle the mental illness situation that we have in the country now, the cops are going to get stuck with it.

Allen: I think it is, at least from what I’ve heard is, and I’m sure you deal with it, is that police officers, everyone, we end up being the area social workers. A lot of this stuff falls to us to have to manage and it sounded like you went through police Academy and learned how to deal with the mentally ill.

Jeff: Exactly. Our jail deputies are dealing with it too, because we meet a lot of people in the jail that are only in jail, because we don’t have a bed anywhere to get them help somewhere else. So, yeah.

Allen: Yep. Cool. Okay. Yep. Thanks so much.

Jeff: It’s been a pleasure. Yep. Okay. Bye. Bye.

.png)