Enjoy this excerpt from one of our published books.

Chapter 2

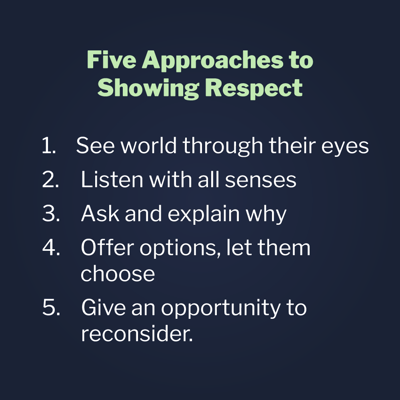

Five Approaches To Showing Respect (Respect Everyone)

In teaching this program to sports officials, I have encountered different age groups, different races, different ethnic groups and officials from different sports. Officials encounter the same types of people. All sports include different ages, races, genders and ethnic groups. Officials need to be skilled in communicating with all of these different groups of people. Sounds like a daunting task. But instead of concentrating on how different everyone is in each sport, Vistelar teaches the five

- See world through their eyes;

- Listen with all senses;

- Ask and explain why;

- Offer options, let them choose;

- Give an opportunity to reconsider.

So let’s first review the core principle of conflict management relative to officiating: treat the players, coaches and fans with dignity by showing them respect. The good official understands that this must occur regardless of the other person’s behavior (this doesn’t mean you don’t sanction or eject when it is appropriate). Take this quote from the North Dakota Highway Patrol: “We treat people like ladies and gentlemen, not necessarily because they are, but because we are.” If you disrespect people, you lose control. You will become the focal point of the conflict because you lost control. Your call or decision may have been correct but no one will care because they will see you as disrespectful towards others. You can sanction someone while still showing them respect. We’ll discuss this later in the book.

One of the greatest ways to show respect before, during and after the game is to acknowledge and listen to what the coaches and players are saying. Some sports allow more time than others to listen to the players and coaches. If you don’t have much time (because the flow of the game doesn’t allow it), simply acknowledge that you heard them and let them know you can talk to them when there is a break in the action. In many instances they just want you to hear what they have to say.

The Process

You start the process of showing respect by being open to listening to the coaches and players. The following story illustrates this point. I was the base umpire for a spring high school baseball game. The spring in Wisconsin is rough on baseball players. It was about 40 degrees, with the winds gusting at nearly 35 miles per hour. The wind was blowing in from right field. As the base umpire, I had to make several close calls at first. I called a runner out at first on a close judgment that completed a double play. This was the third close play that didn’t go the way the team on offense wanted. It was the third out in the inning so after I made the call I began to run to short right field where I stand between innings. I was running right into the wind. While running, I checked over my shoulder to see if the coach was going to come out and discuss the call. He was, so I turned to meet him halfway. He was running in slow motion because of the strong wind. His hat then blew off and he chased it, picked it up and waved at me as if to say “I give up.” He then went back to the dugout. I laughed to myself not in disrespect but because it was funny. He’s a good coach and very professional. I wasn’t going to make him run out to me because of the wind. That would have been disrespectful. We talked later. I told him that I was going to meet him half way. He said it was too hard to run into the wind so he just decided it wasn’t worth the trip.

Listening is not just hearing. It also involves your other senses. Watch the other nonverbals that occur on the field/court and bench area. Instead of daydreaming or checking the messages on your cell phone, pay attention to what is being said and done in the bench area and on the fields and courts. This doesn’t mean you have “rabbit ears” (responding to every little thing that is being said). Are the teams showing aggression toward each other? Are the coaches frustrated with the performance of their team? Are the players frustrated with the coaches? These are just some of the indications that conflict may occur (so you can prepare yourself and possibly prevent any conflict).

Behavior Based Approaches

The other three approaches to showing respect are all conditional based on the behavior of the person you are talking with. In other words, if the coach or player says or does something unacceptable, then you have to act (maybe an ejection). There are ramifications for people who violate the rules of conduct and sportsmanship. We are not saying that you need to stand there and listen and not respond accordingly. Do what you have to do.

Athletic events involve spectators. These spectators include parents, friends and other family members. These athletes are performing in front of crowds large and small, and there is usually someone at the event supporting them. This puts some pressure on the players and coaches. No one likes to fail, especially in front of the people that support them. Therefore don’t be surprised when a player or coach postures during a game. The posturing can be magnified even more when they feel that they are being disrespected, especially in front of a crowd. The posturing may take the form of defiance and/or an emotional reaction to being told what to do. Place yourself in their position. Would you rather be told to do something or would you rather be asked to do something? When possible, officials should be asking rather than telling the coaches and players what to do (approach #3). People are listening (someone may be recording the game) to what you are saying. By asking you show them respect.

Here is an example. The players on the bench during a basketball game are complaining to the officials about fouls not being called.

As the official runs by the bench, he says to the coach, “Keep your bench quiet, I’m not going to listen to that.” Or the official stops play and begins to lecture the bench in front of the crowd. Remember what our goal is here? Do you think that there is a chance that this official will be able to obtain cooperation with players, coaches and the fans? The answer is probably not.

The better tactic for the official is to appeal to the coach. How about this response from the official: “Coach, help me out here and ask your players to stop complaining about the calls.” Find your personal comfort zone in how to rephrase your statement into a question that defuses anger and builds engagement. Use professional language that moves toward generating the 3 C’s.

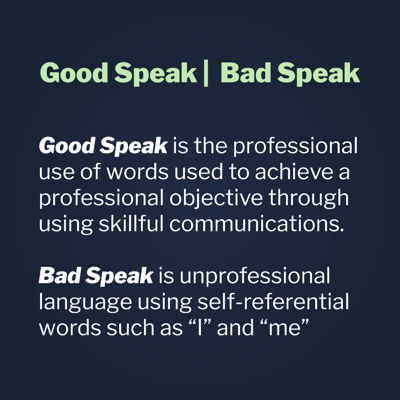

Good Speak vs. Bad Speak

A second example is referred to as Good Speak. Good Speak is the professional use of words used to achieve a professional objective. It puts the official in contact with the players and coaches through the use of skillful communications that is right on target with the audience. The opposite is Bad Speak, which is unprofessional language. The official starts to express his or her personal feelings by using self-referential words such as “I” and “me”. It is not all about you; it is about the game. By using self- referential language you are not in contact with the players and coaches and you start generating resistance from the audience. That will make this a long game.

Officials do not need to explain the reason they make every call. Explanations can interrupt the flow of a game. But there are times when an official can and should give an explanation to a player and/or coach (approach #3). Remember the first Great American Question: Why? Explaining why you ask someone to do something or why you made that decision or call shows respect.

My father coached basketball on the grade school, high school and college level for over 40 years. He was well respected by his peers, players and officials. He was inducted into the Wisconsin Basketball Coach’s Hall of Fame in 2003. Dad had a ridiculously low number of technical fouls (2 or 3) for someone who coached that long. I attended one of his high school games toward the end of his coaching career. One of his players received a technical foul during the game. My dad asked the official what the players had said or done. The official’s response was to walk away from dad. He followed the official onto the floor requesting an explanation and was subsequently given a technical foul. By walking away the official was sending the message “I don’t have to tell you anything and I don’t respect you.” An explanation was warranted in this situation. I once asked my dad the reason for his technical fouls. He said it was because of his frustration with officials that showed arrogance by not taking the time to answer questions. The first Great American Question is “Why”. Take the time to answer the questions when you can. That simple courtesy will begin to generate respect.

There are times that an explanation may not be enough to sway a player or coach. The resistance continues but the official needs to resume the game. If the player or coach’s behavior hasn’t reached the level of an ejection or some type of sanction, then give them some options rather than threatening them with an ejection (approach #4). This leaves them in control of their own situation. It allows them to save face and reduces the chance of them continuing to posture. Threatening people reduces your options and backs you into a corner. Giving them options provides a “wake up call” for the player or coach. It brings them back to reality by saying “Coach, I explained why I made the call and I’m not going to change it. This is a good game, so let’s end this conversation and get the game going. Otherwise I will have to eject you. Work with me here so we can continue the game.”

Here’s what that means in the officials’ head: “I made the call. I understand you are upset. I showed you respect by explaining the call. You needed more time to process the information so I gave you some options you could choose from. What else would you like me to do?”

Approach #5 says, “Give an opportunity to reconsider.” So when it is possible, give them that second chance. There is a great deal of emotion involved in athletics and it’s not going away. As long as that emotion doesn’t result in a level of conduct that needs to be sanctioned, then deal with it appropriately. I have attended many football, baseball, softball and basketball games. A call is made by an official or umpire, and noises erupt from the crowd: the “oohs,” “ah’s” and “come-ons” that come from players, coaches and fans. Sometimes an official or umpire overreacts and starts threatening whoever said something. What do officials expect to happen in these instances? Applause from the crowd? Someone yelling “great call?”

That’s not going to happen (unless the call benefited their team). Also, the younger the player is, the more reaction you may get. Like the 10-year-old kid that throws his bat on the ground after striking out with the bases loaded. Will ejecting him in front of the crowd be a teaching moment or a devastating moment of great embarrassment? Wouldn’t it be better to talk to the coach so he or she can explain to the player how to handle failure? The same is true for newer coaches. New coaches are learning how to coach and how to behave during the game. I believe officials have a part to play in the education of new coaches. That means that we as officials should model proper behavior on the field. You can show them the way by maintaining your emotional equilibrium.

By giving people an opportunity to reconsider you are sending them a message that says, “I understand you are not happy with that call (or no call). You can have a reaction as long as it does not reach a level that conveys unsportsmanlike conduct during the game”. The alternative is having complete silence with no one being able to say anything during the game. That would include players, coaches and spectators. Is that what we really want?

Conclusion

In concluding this section on the five approaches to showing respect, I would like to share this story. In 2004 I had the privilege of umpiring in a state championship high school baseball tournament. I was the home plate umpire in a quarterfinal game. The tournament was played in a minor league ballpark in which the stands were full with about two thousand spectators. The game started with the team (Team A) that was an “underdog” leading the team (Team B) that was expected to win (and did win) their division in the tournament. After a rain delay in the 4th inning, the wheels began to fall off of the wagon for Team A. In other words, they had committed a few errors and were now losing the game. Team A was on defense when a player from Team B stole second base. It was close, and the second base umpire called him safe (the right call). Team A’s catcher walked out in front of home plate and threw his glove on the ground in response to the outcome. He walked toward the pitcher’s mound. I followed him and at the same time Team A’s coach called time out.

Do I eject the catcher or talk to him? The coach began to walk toward the pitcher’s mound. My intent was to talk to the catcher about his actions. The coach said to me, “Pete, I’ll handle this and talk to him.” I told him okay and thanks, and walked to the third base line as Team A’s coach had a meeting on the pitcher’s mound. Team B’s coach came down the line and wanted to know why I didn’t eject the catcher. I explained why and then asked him to return to the coach’s box. After the inning was over the coach from Team A came out to talk to me. He thanked me for allowing him to calm his catcher down. He added that the catcher was a student with a learning disability and that he really appreciated the fact that I didn’t eject him. What would have been accomplished by ejecting the catcher, in front of two thousand people, for an emotional outburst? They lost the game; it was his last game. That would have been his last memory of playing baseball in the state championship. Yes, the behavior needed to be addressed and it was. Sometimes it’s better for us as officials to disappear and let the coaches handle the kids.

Chapter 2 Learning Points

- Everyone wants to be treated with dignity and everyone wants to be shown It doesn’t matter what environment you are in. You could be at the grocery store, at work, coaching in a basketball game or officiating a game. The five approaches to showing respect are the foundation for building this respect. Once you internalize these approaches you will be well on your way to understanding the tactics that are discussed in this book.

- Listening to people is not just hearing what they say. You must utilize all of your senses to gather as much information from that person as possible. Listen to everything happening during the game, not just to a single person. Listen to and see what is happening on the court, field, or bench areas. This allows you make a more thorough assessment of how the game is going. The information you gather aids you in preparing to handle the inevitable conflict.

- The maturity levels of the players and coaches vary depending on what level you are In other words, the new coaches and players on the youth levels need to mature. The younger the athlete, the less mature s/he is. The newer the coach, the less mature s/he is in understanding how to appropriately behave during the game. Therefore it is important “to give someone a second chance” to understand how to act when they feel they have been wronged. It is your opportunity to model proper behavior during the conflict.